The JRB Editor Jennifer Malec chats to Siphiwo Mahala about his new collection of short stories, Red Apple Dreams.

Mahala is the author of the novel When A Man Cries (2007), which he translated into isiXhosa as Yakhal’ Indoda (2010), and the short story collection African Delights (2011). In January 2016, The Guardian listed African Delights as one of the top ten must-read books in the world. He served as the head of books and publishing at the Department of Arts and Culture for over ten years. His dramatic debut, The House of Truth, based on the life of Can Themba, played to sold-out audiences at the 2016 National Arts Festival in Grahamstown, and at the Market and Soweto theatres in Johannesburg, as well as Sandton’s Theatre on the Square. He earned his PhD with a thesis on the life and work of Can Themba in 2018.

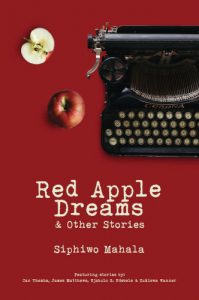

Red Apple Dreams and Other Stories

Siphiwo Mahala

Iconic Productions, 2019

Jennifer Malec for The JRB: You’ve decided to go the self-publishing route with this book (and your previous one, The House of Truth). Could you talk us through why you made this decision?

Siphiwo Mahala: I decided to publish my own work because I wanted to take full ownership of the means of production. In other words, instead of cutting the pie into at least four pieces (i.e. author, publisher, book distributor, bookseller) where, as the author, I remain at the bottom of the hierarchy (getting an average thirteen per cent royalty), I have full ownership of my work. I am at liberty to sell my books in all sectors of society, including townships, where my niche market primarily resides. My family helps me courier books to individuals and bookstores that place orders throughout the country, and I have turned my car into a mobile bookshop. There is an instant response to orders and we are quicker than most bookstores or publishers because my books are a priority to me and my family. This gives us a clear sight of the book value chain and yields immediate commercial returns, as much as it requires a substantial capital base.

The JRB: Red Apple Dreams is a unique collection; I’m not sure I’ve seen anything like it. The book combines your stories, new and previously published, with a selection of stories by other writers. Where did you get the idea to compile this kind of collection?

Siphiwo Mahala: This is one of the advantages of self-publishing, you are at liberty to explore and exercise your creative muscle. With Red Apple Dreams, the initial idea was to reclaim my rights from all my previous publishers and have some sort of ‘family reunion’, where my short stories would all be in one publication for the first time. However, in the end, I could not accommodate everything, so I had to select stories from both the previously published and the new stories. As a student of African literature, there are a number of writers that I have always admired and I dreamed of being in their company in some way. The likes of Can Themba, James Matthews and Njabulo Ndebele are some of the most remarkable exponents of short story writing in South Africa and the giants on whose shoulders I stand. Of course, Zukiswa Wanner is always great company to keep. To be published alongside these icons in my own collection is like having a conversation with them at the dinner table. The resultant product is an intergenerational dialogue, or in scholarly terms, some form of intertextuality, where I either directly reimagine some of the stories by my literary icons, or my stories have resonance with their works. In a sense, I was consolidating my work while at the same time paying tribute to my literary icons.

The JRB: You have published work in many genres, drama, fiction, short stories and also academic writing, but in the Introduction to Red Apple Dreams you write: ‘the short story is the future’. Can you talk a little about why you think this is the case?

Siphiwo Mahala: In an age where time is continuously shrinking, and there’s constant discovery of reading gadgets like Kindles, e-readers, iPads, and so on, short narratives become the most convenient to read. The advantage of short stories, in particular, is that in addition to the brevity that allows you to read them in one sitting or at short intervals, they are also easily adaptable. A short story like Can Themba’s ‘The Suit’, for instance, has been adapted into a stage play, a musical, a graphic story and a short film, with resounding success in each of these genres. Each story in a collection has the potential of taking on a life of its own through adaptation processes. You are not bound to follow a particular thread because each story has its own focus. Much as it is possible to read a short story in one sitting, the converse is also true with regard to writing. You invest less time and energy in writing a short story—but the returns are immense.

The JRB: You are known as a fiction writer, but this book opens with a piece of creative nonfiction, ‘Red Apple Dreams’, centred on your memories of your mother. It’s personal and poignant, and I was wondering if publishing a piece like this changes your relationship with the reading public. Do you feel more vulnerable, perhaps?

Siphiwo Mahala: ‘Red Apple Dreams’ is a deeply personal piece of writing. When I wrote it, I had no intention of publishing it. I was just expressing my innermost feelings on the occasion of the thirtieth anniversary of the passing of my mother. It was only after I shared it with a friend who had also lost her parents at a young age, and she told me how much the story resonated with her, that I began to think of publishing it. She vowed that anyone who has ever lost a loved one would surely find the story worthwhile. Publishing the story lays my soul bare to the reading public, and I have no regrets. In the year I wrote the story, I got to speak about my mother for the first time in thirty years and I have never felt more vulnerable. I cried from the podium in the full glare of family and friends, including my own children. But this somewhat liberated me, and I have been crying less ever since. Writing the story has become some sort of a catharsis. Today I can talk about my mother, something I could not do for thirty years after her passing. If my story inspires, touches or appeals to the sensibilities of any readers, I would consider my role as a writer fulfilled.

The JRB: You’re considered a writer who follows in the tradition of Can Themba, and you’ve mentioned that you are also influenced by Njabulo Ndebele and Sindiwe Magona, writers known for chronicling the sights and sounds of everyday Black life during apartheid. Can you talk a little about how these writers influenced your writing?

Siphiwo Mahala: I grew up reading Xhosa literature and I connected with the characters, particularly in short stories. The prose I was exposed to in English literature was largely the work of Shakespeare, William Blake, James Joyce, and other European classics. In the early nineteen-nineties, I came across To Kill a Man’s Pride, a short story collection edited by Norman Hodge. It was here that I encountered the short stories of Njabulo Ndebele, Can Themba and Mtutuzeli Matshoba for the first time. I can distinctly recall how amazed I was that Ndebele wrote in English that read or sounded like our regular way of talking, and the characters were such familiar township figures. Until that moment, I was not aware that writers were allowed to write about Black people’s lives in the townships, and capture the essence of their lives in character, speech and action. Later on I read Sindiwe Magona’s Living, Loving, and Lying Awake at Night, and it was almost like watching the mothers of my community in a film. I found the characters so familiar and real, and this inspired me to tell my own story the way that I knew it.

The JRB: Stylistically, and in your use of dialogue, I see strong echoes of what Lewis Nkosi calls ‘the fabulous decade’ in your work—perhaps an example of the ‘intergenerational discourse’ you speak about in your doctoral thesis. But thematically, you take things forward. ‘Mr Fiancé’ and ‘Hunger’, for example, illustrate how gender and racial dynamics are changing. Is this ‘updating’ of the tradition something you are conscious of in your writing?

Siphiwo Mahala: My writing is the reflection of my state of mind, my preoccupations or observations at a particular moment. I never deliberately set out to redress racial or gender imbalances when I write, but if these are prevalent in any of my writing, it is probably because it mirrors my lived experience at the time. I have always been surrounded by women (I was the only boy after three girls and now I am the father of three girls), and this is bound to show, one way or another. Similarly, racial dynamics are part of our daily life. As someone who grew up partly in apartheid South Africa, I have the fortune of straddling two critical eras in the history of our country. The socioeconomic and cultural changes, or lack thereof, are the realities of our lives, and exploring these in our literary output is to do justice to the story of the contemporary society.

The JRB: In addition to writing fictional responses to Can Themba’s ‘The Suit’ and Njabulo Ndebele’s ‘The Test’, you also respond to James Matthews’s story ‘The Park’, which is about a small boy who is barred from entering a whites-only playground. What was it about this story that inspired you to continue the narrative?

Siphiwo Mahala: I have a penchant for stories that are written from the point of view of a child. This is a difficult task, because there is always the temptation to reason like an adult while trying to portray a childhood story or a child character. To master the art of storytelling, particularly from the point of view of a child, you need to revisit your own childhood, see the world through the eyes of a child, and translate your imagery to the text in the most authentic way. This Matthews did exceedingly well. The use of a child character in ‘The Park’ is the most remarkable way of illustrating the deep vileness of the apartheid regime. Instead of being preachy Matthews is showing us, and this led to my own reimagining. I began to wonder if the offspring of the protagonist in Matthews’s story would understand the extent or the meaning of freedom in South Africa today. This warranted a revisit to the park, and so ‘The Park Revisited’ was born.

The JRB: The final story in the book, ‘No Man’s Land’, illustrates how South African identities are far more complicated than the dominant narrative suggests. There’s an Afrikaans farmer who prefers to communicate in isiXhosa, and a Black MEC who refuses to let a young man do research on his ancestral land because it threatens his business interests, his economic investment in the land. Your characters are never typical, which I think makes you stand out in South African literature.

Siphiwo Mahala: The characters are familiar people that one gets to interact with on different platforms. Where I come from, for instance, it is common for Afrikaner farmers to speak fluent Xhosa. My late mentor and confidante Prof. Keorapetse Kgositsile, in illustrating the complexity of identities, used to tell me the story of an incident that happened while he was a visiting Professor at the University of Fort Hare back in 1997 (at the time I was a student at the same university). He came with his three-year-old son, Thebe, now a famous American rapper known as Earl Sweatshirt. Thebe, coming from America, obviously spoke English, and their white neighbour in Bhisho (where he stayed), had a son of more or less the same age and they played together. The paradox here was that the white child spoke fluent Xhosa, whereas Thebe spoke English.

The JRB: Most of your stories offer an ambiguous or even bleak view of South African life, so ‘Old Man’s Horse’ is notable to me, because of its air of optimism for the future. Samkelo, who works as a miner in the city, returns to his village for the festive season, and at first it seems as if the story is going to take a dark turn. But it ends on a note of hope; he is able to reconcile his urban and rural identities. I suppose we see this hope in ‘The Park Revisited’ too, in the happy interracial newlyweds. Is your writing becoming less pessimistic?

Siphiwo Mahala: When I write a story, I never predetermine the ending. I allow the story to unfold in its most natural form. The happy endings are coincidental, probably influenced by my love and nostalgia for rural landscapes. What I consciously did in this compilation, though, was to select stories that reflect both the rural and urban landscapes. I was born and bred in Makhanda, I partly grew up in Mavuso village, Alice, and I have been living in Gauteng for about seventeen years now, and all of these aspects are reflected in my stories. My wife grew up in a rural village in Tsomo, and usually tells me stories about their activities, including horse races and parades that are quite common during the festive season in Eastern Cape. Unfortunately, I always miss the village horse races, but my imagination took me there in ‘The Old Man’s Horse’.

The JRB: I have to ask you about your story ‘Robbed by a Mad White Man’, which I believe is inspired by your experience of moving to Johannesburg. What was the genesis of this story?

Siphiwo Mahala: I wanted to respond to a call for ‘crime stories’ for a short story competition, and I tried to think of a criminal act I was involved in. What came to my mind was the fact that, disappointingly, after more than ten years in Gauteng, I had only been robbed once. Just once! This went against the reputation of Johannesburg that I had read about in so many stories and watched in so many films, where people get robbed on arrival at Park Station. The only occasion I had been robbed the culprit was a white man, something socially reprehensible for a supposed township boy. The story was born.

The JRB: You translated your novel When A Man Cries into isiXhosa, as Yakhal’ Indoda. Can you talk a little bit about that process, and whether you intend to translate any of your other work?

Siphiwo Mahala: I studied Xhosa literature up to honours level, and when I started writing I was writing in my mother tongue, it was only in 2001 that I switched lanes to write in English. I remain very passionate about literature in indigenous languages, and it is my intention to contribute to the preservation Xhosa literature through my writing. However, the experience of rewriting When a Man Cries in isiXhosa was a very strenuous endeavour. The computer systems do not, or at least did not, back then, understand my mother tongue, so every word was marked red by the spellcheck. I had to work two times harder than when I write an English text since technology let me down. Going forward, I will do translations, even if one story at a time. Most recently, I co-translated a children’s book for Zukiswa Wanner.

The JRB: Finally, we like to ask writers what they are reading—they generally have the best book recommendations. Are there any new writers or books that you have enjoyed recently?

Siphiwo Mahala: The irony about studying towards a PhD is that I did less leisure reading and more academic texts and material relevant to my research. There is a long list of books that I bought over the past four years but could not read. Since graduating my PhD last year, I have been trying to catch up on both reading and writing, and Red Apple Dreams and Other Stories is the first product of this phase. My reading habits are not yet back to normal, but on my bedside at the moment is The Man Who Founded the ANC by Bongani Ngqulunga. I have also just finished reading Talk of the Town, short stories by Fred Khumalo.