Lidudumalingani reviews Everything is a Deathly Flower by Maneo Mohale, finding it to be a succession of powerful moments.

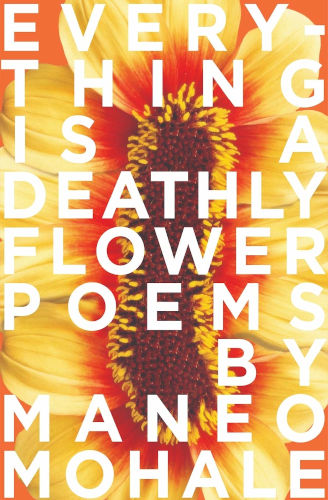

Everything is a Deathly Flower

Maneo Mohale

uHlanga Press, 2019

On page twenty-three of Everything is a Deathly Flower, the debut poetry collection by Maneo Mohale, the poem ‘Morapa-Šitšane / for survivors’ is placed to the far right, almost as if it is apologising for its existence, as if it is trying not to be seen, to be as invisible as possible.

The poem reads:

dear reader,

are you still there?

take a second, now.

breathe //

with me.

This short poem jolts the reader violently and then, in the same moment, abandons them to confront, if not surrender to, their own emotions. Its power is not so much in the words themselves, whose function is to get you to this point: ‘breathe // with me’. No, its power is in the moment that you breathe, heavily, without realising that you had, while reading the poem, while reading the collection, suspended, breathing.

The collection, perfectly mapped and bound into thirty-one poems, is a tapestry on which Maneo dances with elegance, narrating, critiquing, lamenting, celebrating—and comforting, including comforting the reader. The poems are written with the tenderness and knowing of a sage nonagenarian who has seen the world under all shades of realities and, further, through all its fleeting and ugly beauties.

Poem titles are anchored by the taxonomy of flowers, in their contemporary English and scientific names. The names tell of the beauty, pattern and possibility of things—but, also, narrate the dangers that loom. Flowers are tender creatures, it is not enough to nurture them, they must be nurtured carefully, they must be listened to.

In the title poem, Maneo narrates alluringly and painfully a story of being violated and triumphing. Each stanza ends with a sentence from ‘Closet of Red’ by the American poet Saeed Jones, from his debut poetry collection, Prelude to Bruise. Every sentence in this poem is a perfectly shaped raging fire of language and emotion. Even in the moment of anger, of deep hurt, the sentences feel as if Maneo has spent years processing this trauma, has gone through many drafts finding the perfect words, and here they are now, in a book, in all their complete magic.

You do not stop. Instead,

you read my body’s rigidness as Yes. You read my silence as Permission.

You read my closed eyes as Assent. And my turned head

as Of Course I Am Black and Woman and Queer.

What Else Could My Body Be For But Entry

How Else Am I Legible But As Safe To Violate

The poem ends with a definite and daring suggestion: that water, that cleansing, is what ultimately heals; and, too, that the communities that nurture our traumas, and allow us to hurt, slowly usher us into part of the raging river that does not threaten to swallow queer womxn/Black womxn; and that they can float.

We find each other by the water. I leave the foxgloves behind me.

Every petal that fell

From my mouth is a survivor, they are my

mother multiplied, more—there’re always more.

There are many poems like this, whose sentences and stanzas leave one gasping for air—not in a deadly manner, but in one that makes for a succession of powerful moments, in which all the ugliness of this world is laid bare and it hurts to realise, as if for the first time, that the violence we confront comes from within.

Maneo is only twenty-seven years old, and yet they command, not only language, but politics, emotions, in a way that very few writers do. The book is filled with sentences, sensibilities, that are molded in perfection.

In the acknowledgements, Maneo writes, ‘This book is made by many hands’. And so it is, with epigraphs and intertextuality in abundance. In the poem ‘Everything is a Deathly Flower’, it’s Saeed Jones. In other poems, on other pages, it is Kopano Maroga, Nakhane, Jeanann Verlee, Dionne Brand, Keorapetse Kgositsile, Kelsey Savage. In doing this, in adding these layers to the book, Maneo gives the nod to a lineage of Black, trans and queer writers who came before they did, narrating, refocusing, displacing heteronormative writing—or, if not simply only, existing as beautiful witness to one’s own experience.

Maneo moves swiftly back and forth between the personal and the observational; their power, however, is in meshing the two via family, friends, and what they call their ‘chosen family’.

In ‘Google Translate for Gogo’, reminiscent of Ocean Vuong’s poem ‘On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous’, Maneo writes and unwrites the poem. In ‘Detected Language’, they write, ‘Grandmother, I’m sorry I’ve been holding on to this for so long but I want to come out to you, I’m a non-binary demigender pansexual polyamorous queer femme’. The poem is written. A line cuts through those same words. The poem is unwritten. In the ‘Southern Sotho’ column, the poem is blank for the first two stanzas, and one only translates the last one, that reads, ‘Grandmother, like you, I survived’.

Unwritten is perhaps not the perfect term to sum up what Maneo has intended here. The focus is on unsaid but deeply felt emotions. The poem exists but it doesn’t. It speaks to translation—not so much the words, but to generational translations. A queer granddaughter translating/narrating their sexualities to their grandmothers.

The collection is also largely about visibility and invisibility. In ‘Letsatsi’, the poet renders certain proper nouns in lowercase: ‘In school, you meet a man named cecil john / and learn the word pioneer’. Rhodes is insignificant, if not non-existent, as a result. In another poem, ‘Dionaea Muscipula (venus flytrap)’, that thought is expanded upon, or begun anew: ‘make your history digestible // you know exactly what I mean’.

Further extending the theme of being visible and invisible, Maneo uses another technique, leaving a lowercase straight line where a name should be. The collection arrives shortly after many victims of sexual violence have been speaking out, naming their rapists and abusers, and this becomes a grand, kind gesture in seeing them. Here is a poem, insert only a name, your pain, your trauma has been narrated, with intimate care.

The book also innovates in form and structure. This is perhaps where it has moments of imperfection—moments that will not bother most readers, but that, for finicky visually-inclined geeks like me, don’t sit as comfortably as the poems themselves.

Everything is a Deathly Flower is a beautiful, intelligent, personal, political collection. These three sentences, if one can be so bold, capture it, its language, its tenderness, its ethos:

I am thinking about my own untouching, and how I ate my eyes in the dark

The morning I came out to my mother, all my lovers arrived instead

Across this table dimples are still there, but my mother no longer recognises me

- Lidudumalingani is a writer, filmmaker and photographer, and winner of the 2016 Caine Prize. Follow him on on Instagram and Twitter.