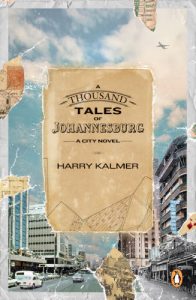

Harry Kalmer won the 2018 Barry Ronge Fiction Prize recently, for his novel A Thousand Tales of Johannesburg. He chatted to The JRB Editor Jennifer Malec about the hidden history of Johannesburg, working with Willem Anker and Marlene van Niekerk, and the process of translating the book.

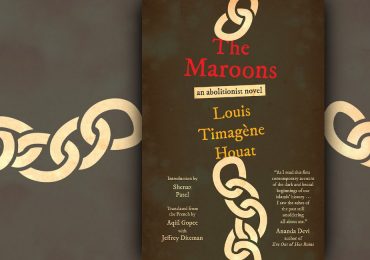

A Thousand Tales of Johannesburg

A Thousand Tales of Johannesburg

Harry Kalmer

Penguin Random House South Africa, 2017

Jennifer Malec for The JRB: First, I’d like to congratulate you on your recent Barry Ronge Fiction Prize—won for your first English novel. That’s quite a feat.

Harry Kalmer: Thank you.

The JRB: One of my favourite aspects of A Thousand Tales of Johannesburg is how the specific places you mention in the parts set in the early twentieth century—Braamfontein Spruit, Mayfair, Turffontein, Emily Hobhouse’s home in Yeoville—help animate the Johannesburg as we know it today. Is that how you see Johannesburg? Are you always aware of the past behind its landmarks and buildings?

Harry Kalmer: The things you mention were very much researched before I wrote about them. I have always been interested in ‘hidden histories’, the stories of ‘little people’, those who aren’t mentioned in the official histories. But in order to tell those stories convincingly you have to attempt to understand the time they were set in. So I needed to delve into the recorded history and cannibalise it in order to reimagine these stories. My approach was that of a writer of fiction and not that of a historian. History is something I use, hopefully, to tell a story more convincingly. A book currently in progress uses the underground white South African rock scene of the nineteen-eighties as a backdrop. I suppose I use ‘facts’ as a springboard for stories. Occasionally I do think about the Foster Gang when I drive up Juno Street in Kensington, and sometimes I remember Smuts’s aeroplanes over Fordsburg when I drive past Cottesloe. But it is not an ongoing thing.

The JRB: One of your characters, Abraham, living in (I make it out to be) nineteen-forties Johannesburg, is a street sign painter, and speaks about the street names—Urania Street, Jeppe Street—as if they are ‘the seven wonders of the world’, because of the history and stories they tell. Another character says he prefers street names to bird names. How do you view Johannesburg’s street names, and their changes? Do you have any favourites?

Harry Kalmer: I do prefer driving down Bram Fischer Drive to driving down Hendrik Verwoerd Drive.

But a street by any other name … as a writer I am more interested in the ‘life’ of a street. Whether Commissioner Street is called Albertina Sisulu or Commissioner Street is almost irrelevant to me—I find the fact that the main part of the street was created in one weekend in the eighteen-eighties by ox wagons heavily laden with rocks driven from Ferreira’s Camp in the east to Fordsburg in the west far more compelling. Thinking about the dynamics. The process was driven by the mines. But who did the wagons belong to? Who drove the wagons? Indentured labourers or boer farm boys? Can you imagine the dust? Also, the fact that big business takes on tasks that should be the domain of government is nothing new to Jozi.

My favourite street is Yeo Street, the play being ‘Jou Straat’, making it my street. I moved there in 1985, bought a house there in 1989. The front of our house fronts on Urania Street, the extension of Yeo.

The JRB: ‘When Abraham finally returns from Ceylon they have so much to say to each other that they never talk about it.’ This sentence, about the Anglo-Boer War and the Ceylon prisoner-of-war camp, spoken by Abraham’s wife, Sara, which in itself makes up of one of the stories in the book, really brings home what a different time we are living in today, where we are in the habit of narrating our every action as it happens. How did you get into the mindset of people living in vastly different times?

Harry Kalmer: I remember, and still know (and often end up liking them a lot), people who don’t have a need to talk. Even in the social media era this is still the case. There are people who have no need or ability to articulate their experiences verbally. My father’s generation served in World War II and would not speak of those times. And it was not an unhealthy silence. My generation of men don’t speak about the Border War. Not talking about that is also common. A lived experience internalised. But I also remember hearing old men talking about their experiences as boer guerillas and prisoners of war on the wireless (as we called the radio then). Like Abraham, both my grandfathers were affected by the war. My oupa Willem Steyn was sent to Burgersdorp prison for a year, my grandfather William Kalmer was a young boy in Woodstock at the time. He told me stories about swapping buttons with the British soldiers and doing chores for pennies. My English father and Afrikaans mother married in the platteland at a time when the Afrikaners and English were at each throats because of World War II. It must have been quite a thing—yet they never spoke about it. These experiences were all touchstones I suppose.

The JRB: ‘May the city to which you return be more beautiful than the city you dream about.’ This is such a lovely line, and there are many touches like this in the book. Sentences such as this suggest a spark of inspiration, and make me wonder if you carry a notebook to jot things like this down?

Harry Kalmer: I do make notes, but I very seldom refer back to them. I suppose things that you write down stick. To me a line like ‘May the city to which you return be more beautiful than the city you dream about’ is as much about rhythm as it is about meaning. Sometimes you stumble upon it but often you craft it until it ‘sings’. I have always had to compartmentalise my writing from the rest of my life, raising a family and earning a living. So I do most of my writing on a screen or on paper. Ideas may spark something, but to bring stories to the page you actually have to write them down.

The JRB: Despite being made up of narrative fragments, A Thousand Tales of Johannesburg is a very compelling book to read. With the different perspectives and storylines, how did you manage to keep the pace so absorbing?

Harry Kalmer: Thank you. I did realise early on that readers may get lost among so many stories. The first convention I established was that writing about the living must be done in the past tense and writing about the dead should be in the present tense. Once I told all the stories I needed to, I wrote a synopsis for each fragment, colour-coded storylines and put them on a wall to see how I could make it work, and tried to arc stories in a meaningful way. Then I added the first twenty pages, which contained just two stories, with the same characters at different stages of their lives. Once the reader was used to that I felt that I could start telling more than two stories at a time. It was also important that the start of each fragment left no doubt with the reader as to which story he was reading, and that the ending created the expectation, ‘What happens next?’

The JRB: Joburg contains many different kinds of societies, coexisting. But this contrasts with a central theme of the book, being the xenophobic violence of 2008—during which intense hatred emerges between these groups of people. You’ve spoken about how one of your favourite things about Joburg is that it looks after people from all over the world. The xenophobic violence must have shaken that notion?

Harry Kalmer: Jozi may have a generosity of spirit and a history of hospitality but inter-community conflict is also part of our history. There were xenophobic attacks on Chinese mine workers as early as 1906. In 1914 the German community bore the brunt, during the nineteen-forties young Anglos and Afrikaners would beat each other up because of the war. And of course 2008. There were other manifestations. Gang wars between communities and even wars ‘imported’ from rural areas into the living quarters of migrant labourers. I am not sure what to make of it. Even something as obvious as stating that it is about resources and the brutality of our history seem facile. The scale and intensity of 2008 horrified me. But the fact is, many of the migrants and refugees have nowhere else to go—so it is more of an organic tolerance and sanctuary than an official policy.

The JRB: I’m interested that after six works of fiction, over twenty plays and numerous literary awards, it was this book that compelled you to enrol in an MA in creative writing. Your supervisors were Willem Anker and Marlene van Niekerk—what was it like working with these esteemed writers?

Harry Kalmer: A Thousand Tales is actually my eleventh work of fiction (we are correcting that on the back of the new reprint). Having Willem and Marlene as first readers really set the bar high. One of the requirements of the Stellenbosch programme is submitting thirty pages each month. That imposed deadline really helped. I enrolled because I wanted to write a longer work of fiction and I needed that type of discipline. Willem and Marlene were extraordinary both in terms of practical critique and suggestions and discussions. I remember one question raised by Marlene—’Who is the narrator of the book?’—which started off a discussion with fellow writer James Whyle and a train of thought that definitely changed the course of the book. We discussed fractals and lists and all kinds of stuff that was very useful in the final format.

Willem and Marlene also pointed me in the direction of writers I didn’t know and reminded me of writers I forgot about. I remember Marlene being particularly offended by the description of a woman’s nipples as ‘ice cream pink’ and that leading to a rereading of Henry Miller’s sex scenes. Then there were the detailed notes at the end of each submission and their sharing of their personal tricks. The process was a mixture of generosity, tolerance and head-butting. I understand objections to creative writing courses but in this case it definitely added to the final product. There was as much discussion and drinking wine as there was teaching.

The JRB: When did you decide to translate the book, and how did you decide to translate it yourself?

Harry Kalmer: The idea of writing specifically about Johannesburg and not writing in English was totally mad. I fully realised that in 2010 when I read to an audience at Boekehuis. People loved what I was reading but didn’t totally get it. Half of my family and many of my friends are English. So the book was a gift to them. My father was an English speaker who spoke perfect Afrikaans. So it is also a nod to in his direction. A man who left school for the first time at the age of fourteen and ended up as an electrical engineer with degrees in the humanities, commerce and pure science.

The JRB: Can you talk a little about the translation process? What kinds of challenges did you encounter?

Harry Kalmer: It took forever and only really took off once the Penguin team came on board and Melt Myburgh and Fourie Botha said they wanted to publish the translation. I have always wanted to write English prose so the challenge was hard to resist. There were references, more tonal than factual, that were not possible to translate so I just skipped those. The big challenge was just to find the time to do it.

The JRB: Does the English book have a different feel to the Afrikaans, do you think? I have only read the English version.

Harry Kalmer: Probably. The languages differ a lot. I think I have retained a sense of spoken Joburg English in the narrator’s voice. I am, at times, a very lyrical writer, that probably got lost a bit. Once I completed the translation the original text just became a source of fact. The spirit of the book was retained, but the English translation got a voice of its own. To the best of my knowledge neither the editor, Michael Titlestad, the publisher or myself ever referred to the Afrikaans as a benchmark. I had no literary ambitions, I just wanted to tell the story without making too many errors. I wrote without the baggage of thirty years of writing Afrikaans prose that does its best to hides its literary tracks.

The JRB: I was interested to see that the lines from Totius’s Trekkerswee at the start of each section were translated by Rustum Kozain, who is The JRB’s Poetry Editor, with some input from you. How did that process differ from translating the prose?

Harry Kalmer: It happened really fast. I don’t know Rustum well, but I’ve read and reread him and I love his blog, and with him share a love of Walcott. I approached him because I got a sense from his books that he knows Afrikaans poetry and Afrikaans well, and that he has an affinity with the longer poem, which Trekkerswee is. I’ve always liked his poetry. So I asked him and he agreed. I know I am being credited with input at the back of the book, but I am not sure what it was. I think he did a great job.

- Jennifer Malec is the Editor. Follow her on Twitter.