Mbali Sikakana considers Nozizwe Cynthia Jele’s new novel The Ones With Purpose in the context of Hilton Als’s groundbreaking 1996 sociopolitical manifesto The Women.

The Women

The Women

Hilton Als

Farrar Straus Giroux, 1996

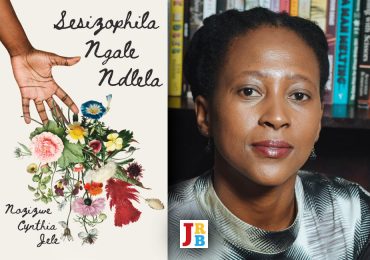

The Ones With Purpose

Nozizwe Cynthia Jele

Kwela Books, 2018

Here go the hindsight

8 years been one long blindside

I could pinpoint 7 more turns that occurred cos he never really healed from the first

Oh what a world —Aesop Rock, ‘Get Out of the Car’

1.

Nozizwe Cynthia Jele’s The Ones With Purpose opens with the death of Fikile, a much-loved sister, and though the death seems to fell the fragile Mabuza family, it soon becomes clear that this is the final blow rather than the first. The narrative unspools, uncovering what seems like a genesis event, only to yield to more powerful contenders. A father’s death makes way for postpartum depression, which makes way for a miscarriage. The tape takes turns fast-forwarding and rewinding, in the days towards Fikile’s funeral, through chapters on alcoholism, unemployment, depression, child neglect and teenage pregnancy, as well as the abuse the latter leaves in its wake. The loss of a job and the decline that follows is described as ‘the beginning of the end of our lives’.

Woven within these stories of how family tragedy compounds on itself, like negative interest, are larger questions, national in nature and spanning generations. What is the true sickness? Depression, which feeds on the devastation wrought by personal tragedy, or the pathologies of history, which are revealed by the systemically diminished fortunes of one’s forebears? When a mother is unable to fully become, and her daughters meet the same fate, where does one stop and the other begin?

The cruelties of life leave one all the more incredulous when the predictable pecking order of Black generational and family suffering is added to the mix. Those with the misfortune of being born first bear the brunt—but even more so those who are born first into the unfortunate universe of Black womanhood. Anele, the narrator, is set to take over where her sister, Fikile, the ox and first sacrifice, left off. As a nurse, a caretaker and reconciler, she bucks against the inevitability of her martyrdom, and as a result is wracked with guilt. Her mother, the domestic and nanny in her youth, proves unhelpful.

2.

Because my mother spent most of her time dying, many women she knew—my father’s sisters, my sisters, one or two of her neighbourhood friends—created a circle around the event of her long-anticipated death. These women knew there was power in it. Some of them co-opted it as the greatest event of their lives. —Hilton Als, The Women

Old friendships were rekindled; aunties who were present in our childhood but had not set foot in our house in years […] once more made appearances. They told Ma how proud they were of her for bravely tackling the devil by the horns. They denounced alcohol, and in their high-pitched voices declared a new war on this destroyer of families.’ —The Ones With Purpose

In his 1991 book The Women, Hilton Als describes Black womanhood as Negressity, a state of being for those transcribed, by society, into the category of ‘the Negress’. The term implies a matrix of identities, derived from both assumed and real impingements on the psyches of black women as a class—of targeted oppressions along the intersections of race and gender. Because ‘Negress’ positions black women as an abstract caricature, it simultaneously lampoons the society that employs it for its lack of imagination—but also allows for a space of secret and gleeful resistance. Negresses, in other words, both perform Negressity and subvert it.

One of the ways Negressity is imposed and performed is through the use of grief, struggle and pain, which are deployed as a thread tying together community and sisterhood. Jele satirises this feverish, opportunistic and ad hoc fellowship in the opening of The Ones With Purpose, where Anele is in the throes of watching her sister die of cancer. Her mother, who lives in denial of this reality, compounds the burden on Anele and, as a result, Anele begins to believe that by being pragmatic—by seeing things as they are—she is going against sisterhood, and thus helping to usher her sister towards death. But Jele rescues her Negresses from the caricatures imposed on them by society, which they are made to perform, with dialogue. Their speech is their gleeful resistance: Jele’s English dialogue mirrors indigenous language preposition choices and makes translations obvious. Anele dishes out food instead of dishing up. People sleep on beds instead of in. The rhythm is of South African, Black, second-language English speakers, speaking and translating at the same time. It helps to locate the story with specificity, placing it within a particular context, since allowing the narrative to become too generalised would open up contentious questions about how Black people are presented and ‘explained’. The space the book occupies is a self-contained universe, with a timeline in which people can grow and change.

3.

For this the men—opprobrium fill their new-grown paunches—showed no extraordinary stomach, preferring to sit in the shade of large bodwe trees or beneath the cool grass of huts built by women, drinking ahey, breathing the flattering air of the shade, in their heads congratulating the tribe of men for having found such easy means to spare itself the little inconveniences of work while yet enjoying so much of its fruit—so easy it is for men’s feet to dance off the way of reciprocity. —Ayi Kwei Armah, Two Thousand Seasons

The sun was going down and the men were at the back of the house feasting on traditional beer and biltong someone had brought along. Aunty Betty became agitated. She and Ma cornered the animal, held its feet together and with a single, precise movement, Auntie Betty slits its throat. The goat jerked once, and died with a whimper. I was sent to fetch a bowl, which Ma placed under the goat’s bleeding neck. […]. They proceeded to skin the goat, hanging the skin to dry, cutting off the head, carefully separating the bile, and cleaning the offal and organs and the carcass. By the time someone at the back shouted, ‘Imbuzi,’ Ma and Aunty Betty were preparing the fire to boil the tripe. —The Ones With Purpose

In the optimistically named New Hope Township in The Ones With Purpose, relations between men and women are strained. Whether in romantic or familial relationships, intimacy is constrained by labour dynamics. It has ever been thus: witness the imbalance of intellectual, emotional, domestic and other labour as observed by Ayi Kwei Armah’s narrator in his 1973 novel Two Thousand Seasons, who laments a lack of reciprocity from men.

The women of New Hope count the cost of this among themselves, before getting on with the job of doing. Since labour-time inversely determines leisure-time, the men seem to have heaps of the latter and use it to get up to no good. The blow is doubled and provides plenty of material for women’s communal or private laments. Throughout the course of the novel, confrontations and separations yield little as time plods on. Men who do well by the metric of labour either die early or deceive for love, leaving the women with the grief of the subsequent disappointments. It is a grim picture, to be sure, but not one of Jele’s making.

One is left to wonder, however, what the resolution of this internal dilemma might be. Does Jele, like Als, believe that women have one of two choices: to deposit of one’s hopes in compromised unions, leading to the banality of conventional suffering, and all its attendant pathologies, or to make a radical break and choose to control one’s own demise, in exile from convention? It is a conundrum that the narrator, at the end of the book, finds herself wondering about, too:

I wait and wait and wait for an answer that I know will not come … —Anele

Negressity, we are given to understand, with this bleak certainty as backdrop, and despite the small victories of resistance against and within its enforced performances, cannot be counted on as a mother of invention. In the end you cannot subvert grieving, for others, for yourself.

- Mbali Sikakana is a Masters in Publishing Studies graduate from Wits University. She has a passion for the entire value chain of writing and books, and is co-host of the podcast Interns’ Insider 2 Publishing. Follow her on Twitter.