Tracing the memory of bones, ‘a long thread of words that attempted to fulfil the universe’—Lara Buxbaum reviews The Old Slave and the Mastiff by Patrick Chamoiseau.

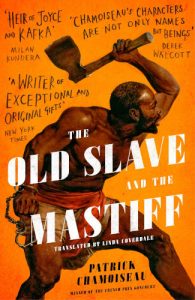

The Old Slave and the Mastiff

Patrick Chamoiseau (translated by Linda Coverdale)

Dialogue Books, 2018

In her poem ‘A Prospect of Beauty and Unjustness’, Gabeba Baderoon writes of a sunset walk in Cape Town, ‘through the old silences of the city’. These silences are the quotidian ones that accompany the close of day, but also the silences of the city’s ghosts. The deaths of earlier inhabitants—including those who first named Cape Town ‘Camissa’ (mentioned in Baderoon’s ‘Port Cities’)—remain unheralded and mostly forgotten. Baderoon recalls how:

Sketching the streets, the artists stood

on the burial ground of the city’s slaves

while above:

[…] starlings shadow each other

and double back on their own flight paths,

slipstreams of warmth,

blood-trace of the self.

These traces of slavery haunt city streets and landscapes around the world, where ‘In the last flash of the sun, the city glints / white and hard as bone’.

It is these silences and ‘blood-traces of the self’ that Martinican author Patrick Chamoiseau sings of in the seven chapters, or cadences, of The Old Slave and the Mastiff. First published in 1997 as L’Esclave vieil homme et le molosse, the novel, which tells the story of a slave’s flight from his plantation and the dog-led pursuit to recapture him, was translated from French into English by Linda Coverdale in 2018, and won the 2019 Best Translated Book Award. The fabular and ‘folktale parlance’ of the novel, along with its concerns of unearthing lost histories, ensures that a book that first appeared twenty years ago is as urgent and alive when read today. It meets Marie-Sophie Laborieux’s memorable desire, in Chamoiseau’s critically celebrated epic city novel, Texaco, for:

writing informed by the word, and by the silences, and which remains a living thing, moving in a circle, and wandering all the time, ceaselessly irrigating with life the things written before, and which reinvents the circle each time like a spiral which at any moment is in the future, ahead, each loop modifying the other, nonstop, without losing a unity difficult to put into words [.]

—Texaco, first published in 1992; 1997 English translation by Rose-Myriam Réjouis and Val Vinokurov

This description is apt for both works, in fact: the sprawling Texaco and the more linear The Old Slave and the Mastiff, which is incantatory and conjuring, elusory and allusive, alive and sensual, echoing and predicting other writings and stories.

The English edition of The Old Slave and the Mastiff includes: an opening provocation (‘Does the world have an intention’); the entre-dire of selections of works by Édouard Glissant, alongside anonymous epigraphs which preface each cadence; the translator’s note and afterword; and a glossary. This series of texts ‘irrigates with life’ and also unsettles one’s reading of the novel, while Coverdale’s notes prove invaluable in identifying influences and contextualising Martinican references without foreclosing interpretations.

Rather than the more celebrated Martinicans Aimé Césaire or Frantz Fanon, it is Glissant under whose sign Chamoiseau writes. In a 1997 interview with Lucien Taylor, Chamoiseau said that encountering the use of both Creole and French in Glissant’s writing ‘was the shock that freed me up to write my first novel’.

Éloge de la créolité (In Praise of Creoleness), the manifesto published in 1989 and co-authored by Chamoiseau, Raphaël Confiant and Jean Bernabé, begins, ‘Neither European, nor African, nor Asian, we proclaim ourselves Creole.’ A riposte to Négritude, but also, as Taylor explains, a criticism of Césaire’s political legacy in Martinique. The so-called Créolistes are not without reproach or controversy, yet in a positive rendering of their philosophy, as Taylor glosses it: ‘Both the Eurocentric and the Afrocentric mirages repress the melange of Creole culture, its open-ended, “multiple” identity: an identity imagined not as “roots” but “rhizomes”, and exemplified by the polymorphous mangrove, that ubiquitous figure of the Antillean landscape’.

In Writing in a Dominated Land, which Coverdale considers as ‘theory’ to the Old Slave‘s ‘practice’, Chamoiseau follows Glissant in celebrating the openness of Place over the restrictions of Territory:

Dreaming-these-possible-Places underneath Territories on which we’re confronted by innovative dominations … Densifying this Place-possible-Martinique through a detailed exploration of a diversity established as valuable. Following the trajectories of this Creolity, praising its components, giving flesh to its holes, and speech to its silences, offering clairvoyance to the events as yet undetectable. At all times searching for the symbolic levels where all will move toward self-renewal. O the praises of this dream!

—translated by Cecelia Ramsey for Asymptote

In Chamoiseau’s 2018 book Migrant Brothers: A Poet’s Declaration of Human Dignity, translated by Matthew Amos and Fredrik Rönnbäck, the invocation of Glissant’s theorising of globality and the poetics of relation, as well as a dream of hospitality, shared ‘self-renewal’ and beauty, become all the more imperative.

The Old Slave is astutely translated by Coverdale, whose ‘Translator’s Note’ explains her decision to retain ‘Martinican Creole and creolised French words’ in the English version. If the context doesn’t sufficiently clarify the meaning, then Coverdale has created a kind of bilingual compound word or added a short English phrase, while the glossary accounts for words that require more historical or linguistic unpacking. This is usually a fairly unobtrusive approach, but occasionally results in potentially dizzying moments in the old man’s flight, such as:

My wounds were beyond counting. Clawed. Griji-grazed. Skinned. Froixé-bruised. Swollen. Zié boy, half-blind eye. Blesses, hidden-hurts […] It galloped, I felt, in the obscure grace that had allowed me to penetrate the zayon-wilderness better than a spectral Dorlis. Ne plus courir, me battre. Not to run anymore, to fight. Fight it. This resolve dismayed me. Excited me as well—truly unexpected.

For this reader at least, the odd pairing of the Creole and English words functions to successfully ‘match’, as translator David Bellos proposes, the mixture of Creole and French and thus the mode of the original, as well as maintaining the strangeness of the translation, or simply reminding the reader that the English novel is in fact a translation.

The first cadence of The Old Slave, ‘Matter’, opens with the words of the narrator, whose reflection on his ‘obsession’, this story, bookends the novel. He notes that:

Stories of slavery do not interest us much. Literature rarely holds forth on this subject. However, here, bitter islands of sugar, we feel overwhelmed by this knot of memories that sours us with forgettings and shrieking specters.

While the grand claim of literature’s aversion to slavery is dubious at best, it might be a tactical fallacy. In merely a few paragraphs in The Old Slave, Chamoiseau conjures in language biblical, fragmentary and elegiac the terrors of the slave ship crossings, and the deadening experiences of plantation life—which the reader encounters as if for the first time.

The ‘slave old man’ is an elusive and ‘opaque’ protagonist; his name is never revealed—neither his real one nor ‘the ridiculous one conferred by the Master’. His existence is solitary and defined by negation, and he resists all improbable identities and clichéd roles projected onto him by the others.

It is only in the description of the storytelling that he is briefly accorded a disconsolating solace and referred to by the shortened appellation ‘old man’, briefly relieved of the mantle of slavery, which is removed permanently once the forest chase begins. In a Beckettian echo, the:

Papa-conteur‘s words […] give him flesh in the flesh of others, memories that belong to all of them and quicken them all with a wordless throbbing. […] there are so many shattering and bewildering presences in the old man that he must (like the other slaves) increase the inertia of his skin […] He must go on with these forces inside him, maladjusted beyond measure, which do not explain anything to him about himself, or about so vast a life in this most cramped of deaths.

The mastiff endured the same oceanic passage as the slaves and was brought to the plantation specifically to hunt down would-be escapees. The old man’s singularity is extended in his tenuous, mirrored relationship with the monstrous hound as he ‘rediscovers in the mastiff the catastrophe inhabiting him’. This ‘dog is the master’s rudderless soul. It is the slave’s suffering double’ and it will be responsible for tracking the man down as he finally accedes to the décharge, the overwhelming urge to flee the plantation.

The mastiff may remind readers of the mythical Cerberus, the three-headed hound guarding the gates of Hades, or of the grotesque prison guard dogs in Jesmyn Ward’s Sing, Unburied, Sing. However, the translated title, while still evoking its immense mass, tends to domesticate and truncate the ancient lineage of the canine Molossus, which appeared in literature as early as the first century AD in Satyricon as protector of both Trimalchio’s house and his slaves; in 400 AD, the poet Claudian mentions ‘deathless Molossian hounds’.

And with the narrative disclaimer, ‘I will, without fear of lies and truths, tell you everything I know about this. But it’s not much’, begins a nearly eighty-page-long katabasis, a race into the depths of the Great Woods where the old man is tracked by the mastiff and his master. There is considerable potential for tedium and only a storyteller as wildly inventive as Chamoiseau could render such a chase so exhilaratingly. It is a hallucinatory journey that details the encounters of ‘the old man who had been a slave’ with the ‘sensory topography’ of the woods. Chamoiseau’s technique creates an oneiric, musical quality to the text, the immersive and surprising nature of which is best left to the reader to experience first-hand.

Amid this praise it is worth noting that the novel—or its translation—contains moments of failure of imagination, or the reinscribing of damaging stereotypes. At one point the man is simply ‘scared shitless’, a stunted phrase which jars in the poetry of his run. The depth of the wood is described as ‘vulva dark’ and there is, improbably, an occasion when the slave trips and ‘[a]n andièt-sa—hateful-clit-hole—swallowed me into its darkness’. Perhaps this is unsurprising in a novel in which only one woman is given a one-sentence speaking role, but disappointing from a writer who also gave us Texaco‘s luminous Marie-Sophie Laborieux.

Midway in the journey the third person narrative shifts into the first person. This change at once announces the wished-for subjecthood, liberation and awakening of the man as well as the merging of his voice with that of the Word Scratcher, of whom more shortly, who discovers the bones that catalysed the old slave’s story.

The search culminates in the descent into an abyss, the ‘center of luminous shades’, and the climactic rediscovery of an Amerindian stone engraved with ‘a ouélélé-tumult of myths and Geneses’—a palimpsest of stories. This stone echoes the storytelling and provides the man with both illumination and succour:

These people had inhabited this country for an et-cetera of time, and carved stones this way in the Great Woods. I had learned of their extermination. Old Caribs had taught me about plants, fish without venom, and companion roots. They had unfolded (for me who cared so little) the narratives of their people: the times before-time, the first times, the lost-times—a long thread of words that attempted to fulfil the universe. […] I had wanted them to teach me how to survive right here where I was, but they discoursed on their past being, at the center of all things. I had not listened. Youth. Here, now, I hear all that again.

The parenthetical comment, juxtaposed with the concluding thought, emphasises the note of didacticism present in the novel. There is an insistence on the value of past knowledges beyond merely the pragmatic concern with contemporary issues. It stresses the need to resuscitate and decipher—or merely be attentive to—the stories of old and thus contribute to the ‘long thread of stories’ which makes the universe whole, which realises the world’s intention to create and tell stories.

While the old man does not live to return, he is described as a ‘warrior’ who is ‘unconcerned with conquest or domination’ before his demise: until the end he is resistant to binary logic. Both the mastiff and the master are utterly, idealistically transformed by their own descent into the undergrowth, the underworld:

In [the Master], now, other spaces were bestirring themselves, spaces where he would never go, perhaps, but where one day no doubt, in a future generation, hopefully in the full radiance of their purity and legitimate strength, his children would venture, as one confronts a first misgiving.

In the closing chapter of the novel, cadence seven, ‘The Bones’, the Marqueur de Paroles—Word Scratcher—reflects on his decision or lack thereof to write this story:

I was the victim of an obsession, the most distressing, exhausting, and familiar one, the sole escape from which is Writing. To write. I thus realized that one day I would write a story, this story, molded from the great silences of our mingled stories, our intermingled memories. About an old man slave running through the Great Woods, not toward freedom: towards the immense testimony of his bones. The infinite renaissance of his bones in a new genesis. I should not have touched [the bones].

One might wearily consider this and other interpolations by the narrator a tired postmodern affectation: the interruption of the author-figure a gesture designed merely to trouble the reader’s absorption in the world of the book. Yet the Word Scratcher, a sobriquet Glissant bestowed on Chamoiseau, is also a reference to the Creole storyteller—whose call-and-response narratives occur in a masterly, galvanising set piece in the novel—and to the desuetude of the traditions of oral literature and storytelling. And thus the novel is not merely a reanimation of and elegy for the Amerindians and the slaves, but also the storytellers of old and the histories, ghosts, forestine landscapes and chimeras of their tales—whether spoken or engraved.

The bones, after all, remain anonymous. The Word Scratcher admits: ‘They could have been from anyone among us. Amerindian. Nègre. Békè. Kouli. Chinese. They spoke an entire epoch, but one open in its uncertain totality’. This lingering doubt signals the myriad of other bones waiting to be creatively resurrected, of other restless spirits awaiting communion. In reading this narrative, the reader becomes complicitous in the Word Scratcher’s guilt and fear about touching the relics and disturbing the dead, and similarly wishes to assuage the guilt by honouring the dead. Ultimately then, The Old Slave and the Mastiff leaves the reader to reckon with the untold stories and memories in cities which still glint ‘white and hard as bone’.

- Lara Buxbaum is a sessional lecturer in the English Department and Wits Plus, Centre for Part-Time Studies at Wits University.

One thought on “An exhilarating elegy for the slaves and storytellers of old—Lara Buxbaum reviews Patrick Chamoiseau’s wildly inventive novel The Old Slave and the Mastiff”