Kim M Reynolds considers the historical and the personal in Uhuru Portia Phalafala’s new book Mine Mine Mine, in discussion with the author.

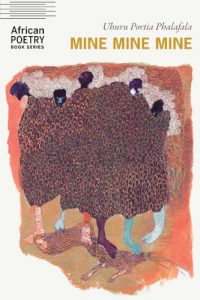

Mine Mine Mine

Uhuru Portia Phalafala

University of Nebraska Press, 2023

‘… in guaranteed poverty while unearthing wealth’

Uhuru Portia Phalafala’s 2023 collection Mine Mine Mine is a map constructed around many things that can no longer be seen, heard, or mapped. The disappearing but persistent force that Phalafala excavates is the mining industry in South Africa and other southern African countries, and how it has interrupted and irrevocably transformed, as well as ended, the lives of Black people.

Many years ago, I found myself sitting next to Uhuru Portia Phalafala at a lunch. We knew each other through some mutual friends, but it was the first time we had spent enough time together to chat, to really talk.

I asked her about her work, and she said she was writing about Blackness through jazz. I responded by asking, ‘So you’re writing about Black jazz slash Black jazz artists?’ She graciously corrected me that no, she wasn’t writing about music. She said again that she was writing through jazz, jazz being a modality that Black people often live.

There is an improvisational element to living. You have to constantly create, on the fly, in real-time, new ways of being and new ways of doing under conditions of constant siege and anti-Blackness.

In Mine Mine Mine, Phalafala’s modality and orchestration are not only evident but masterful. When I asked Phalafala again about jazz, in relation to the book, she said,

My book Mine Mine Mine, for instance, is ancestrally co-written. My grandfather visited me after his passing to narrate his story to me, our story. I’ve had to devise rituals to be present with him and hear him, to fetch from where he is—what you might call ‘the outside’—this story of our people. Jazz improvisation works like that: you depart from this known world (the inside of dominator culture), one structured by particular logics and sensibilities; you leave it to enter the world of the unknown (the outside), where perhaps you are known or at least knowable, where you are accompanied, where you experience pastpresentfuture, and where you occupy geographies that unsettle settler geographies and logics of being. Then, whatever you live and see and hear in that unknown world, in the outside, you return to us here, to rupture dominator knowledges, transcribing it, as I did in Mine Mine Mine. I call this process reeding and riting, which gestures towards a radically different literacy system of ‘writing as ritual’ (my book Keorapetse Kgositsile & the Black Arts Movement: Poetics of Possibility comes out in February 2024, and unpacks this at length). So when I speak of jazz I speak of that which exists in the outside and refuses to be scored, notated, standardised and transparent. It also defies the material fundamentalism of western being, knowing and doing, since it insists on the existence of otherworlds, here; it is a dance beyond the margins of what is ‘real’, a dance in the outside of what is given or granted as reality, as sensible, or as civilised. We reed it ‘there’ and make language to be able to write it for these times. Musicians and other artists, those who experience a close relationship with the unknown or the outside, speak of song visiting them in dreams, of catching songs from the spiritual dimension, or of feeling guided in the making of their art. They reed what they see there—in dreams, during go phahla, in ritual—and rite it in this realm for us. This is the method and modality of all my work, and jazz is an example par excellence in terms of bridging and bringing those worlds into co-existence.

Mine Mine Mine opens with,

In 2018 a historic silicosis class action lawsuit against the mining industry in South Africa was settled in favour of the miners*

*The miners are dead.

Phalafala is concerned with the phenomenon of living while being dead, of being killed while still breathing, of being extracted but still living, of not living but surviving. Phalafala may be a scholar of race and literature, but Mine Mine Mine was born out of an interrogation of her grief. When Phalafala’s grandfather died, she realised she didn’t know him very well, and wondered what had caused that condition. Reaching through her family’s ancestry, she arrived at various interruptions imposed by the South African mining industry and the larger system of racial capitalism. Her grandfather, like many men who worked in Johannesburg’s mines, came home only once a year, a state of affairs that fractured so many families. Mine Mine Mine is as much about Phalafala’s personal history as it is about the wider impact of the mines.

Mine Mine Mine interrogates time and realms. Seemingly, an event like the collapse of a mine slope, killing young men, happens once. The mine cannot collapse on itself again, can it? Phalafala demonstrates that it can, perhaps two generations later, in a different form. The mine could collapse again through miscarriage. The mine could collapse again with the realisation that you do not know certain songs, recipes, or stories, because they could not be passed on. The mine could indeed collapse again.

Phalafala captures the reoccurrence of seemingly unique events in stanzas that use alliteration and rearrange the same words to construct similar but different meanings:

Rotating between pregnant and breastfeeding

Grieving a miscarriage and pregnant

Breastfeeding after a miscarriage

Grieving a stillbirth while pregnant

Bleeding a miscarriage while breastfeeding

Pregnant, grieving and miscarrying

Grieving infertility after still birth

Breeding, feeding, and bleeding

Breastfeeding a stillborn

while grieving a miscarriage

Grieving postnatal breeding

Ke motswetši ke imile ke a hloboga

Ke imile ke a hloboga ke motswetši

Ke motswadi wa go hloka sestswetši

Motswetši was go hloka lesea

Later, she uses this device again, to think through the patriarchal violence that is birthed out of colonialism:

Breaking, breaking, breaking

Break your body for my lineage

Break your body for my children

Breastfeed my children

Don’t breastfeed in public

Fix your saggy breasts to breastfeed me

Climb ladders of success

But don’t pass me

Make money but give it to me

Doctor at work, wife at home

CEO in the office, slave in my kitchen

Make dombolo, make lasagna

Don’t wear waist beads

unless on top of me

Don’t talk back to me

Don’t ask me questions

Don’t take birth control

Don’t be pregnant again

Don’t have an abortion

Why are you pregnant again?

Be a mother and a virgin

Be a whore in my bed

Be conservative and respectable

Be adventurous. Kiss a girl

Only for my pleasure

Don’t.be.a.whore.outside.my.house!

Restore your birth canal,

Be a virgin, be a mother

Bleach your vagina and your face

I don’t like makeup

I like tall dark dandies

Be a yellow-bone Lupita

Mine Mine Mine is written as an epic, with six movements and two parts. The six movements of part one, titled ‘Mine’, are lengthy. The text reaches from the top to the bottom of the page, flowing from analysis, to scenes between people, to her grandfather’s voice. The text is incredibly transportive, even more so live. At a reading of Mine Mine Mine at the Chimurenga Factory in Woodstock in late 2023, Phalafala conducted an extended recitation of parts of the collection, using a train whistle, her own singing and intonation, and the silence and attention of the audience. The performance breathed life into the words, which are grasping at life so tightly, but keep coming up short at the hands of racial capitalism.

The epic form of the collection facilitates this grasping, in a particularly intimate and feminine manner. Historically, the epic has been considered a masculine genre; there are many tales of triumph or adventure that focus very little on interiority. Phalafala explains that she wanted to write in the tradition of her mother and other women in her life:

As a literary scholar, I’ve been taught the epic as a male tradition—from Chaucer and Milton, Dante and Homer, to Dhlomo and p’Bitek—concerned with the heroic. The epics are concerned with a forward thrust towards resolution, acting upon history towards climax. The epic as I was taught was phallocentric.

I wanted to lean into process, into the ways of my mother and her sisters’ storytelling, their narration of the everyday with the rigour and passion of explorers, their erotic language of interiority, of spirited expression waged from the body, their ways of being present with the problem instead of trying to resolve it, their care around language and its sheer enjoyment. I wanted to write an epic in the tradition of the mothers, so I was heartened when one of the blurbs for the book commented on this particular feature.

Phalafala discusses, maps and interrogates hundreds of years through these seventy pages. Prose and poetry in epic form make this kind of quest possible, because the exploration is loud, it is boisterous. It is difficult. Therefore the epic swells, and the first part of the collection stretches out. The six-part section screams and yells; it feels like madness as much as it describes madness. There are high peaks and loaded sentences that necessitate a moment to stop, and feel.

By the second part, which is titled ‘State of Mine’, the work is a little quieter, a little more hushed. Part two learned from part one, in that it learned of the death, and the racial capitalism, and abuse, and dysfunction, and misspelt iterations of love. And it offers concise analyses of violence, and its shorter stanzas still corral the death-making machines and systems that are their subject.

Phalafala likens the epic form to musical scales, revealing another double meaning lodged in this collection:

I knew the lungs are contaminated by mine dust, but in fact it’s something larger than that—history, in its climatic anti-Blackness. I knew this had to do with extraction and plantation economies in South Africa but also the Black diaspora and the trans-Indian Ocean diaspora brought to the Cape and Natal at various points in history. The geography and temporality of this violence is expansive and centuries deep, I realised, and the scale of violence is atomic, cellular, in the lungs and organs, as well as present in our everyday lives: who and how we love, who fathers us and our children, and in national and continental politics. An epic would be an apt form for this, for the narrating of these scales (a jazz concept that works well as a metaphor for these multiple iterations in various registers, tonalities and vocabularies).

In addition to influences such as Katherine McKittrick (the author of Demonic Grounds), Saidiya Hartman, Fred Moten and Keorapetse Kgositsile, Mine Mine Mine, makes connections to the transatlantic and trans-Indian slave trades:

America,

America,

arbiter of morality

enemy of dirty communists

assisting apartheid apprehend and assassinate

Black antiracist activists through severe surveillance

and perverse alliances to subdue revolution

Jim Crow and apartheid sitting in a tree

K-I-L-L-I-N-G

Apartheid and Thatcher sitting in a tree

K-I-S-S-I-N-G

French-kissing federal intelligence

building iron curtains with our gold

intercepting and infiltrating insurrections

chasing imagined red peril and rooi gevaars

The atrocities in the United States and South Africa do rhyme. The exacted forms of segregation, the discursive colonialism and dehumanisation of Black people, the medical warfare and experimentation, the expropriation of land, and the exclusion of Black people from the law and public life, all have the same prosody. And as devastating as these realities are, they are replicable as a song. The melody is playing out in Palestine at this very moment, where the US and other Western countries fund the genocide of thousands of people, and circulate routine talking points to justify seventy-five years of killings, aggression, sexual abuse and racism. Phalafala’s writing here is a schoolyard rhyme that chills.

But for all its excavation and specific references to death and abuse, Mine Mine Mine doesn’t raise questions of justice. One does not reach the end of the collection with any kind of resolution. In fact, the collection almost begins again with the last verse:

Gold and diamond mining

is the white pot

at the beginning

of the rainbow

nation

There is no closure, as no intervention that can address what has happened and what continues to occur. For Phalafala, the end of the work is its most significant section:

This is an unpayable debt, as I state in the epigraph of the book. It is one incalculable catastrophe after another, the foundation and fuel for this modernity, this civilization. There is no justice. The only thing worth beginning, as Aimé Césaire teaches us, is the end of the world. Black feminist work teaches me to imagine, create and inhabit the world of our making in the now. Black feminist cultural and political labour lights in me alternative neural pathways for sensing into history, process and what we might regard as repair.

Black feminist work also offers world-making tools. One of these, citation, is braided through Mine Mine Mine. Scholars, artists, mothers and sisters are quoted as integral parts of the collection, and all are to be found in the notes. And while the debt is unpayable, there is an urgency to witnessing:

This is intergenerational work, ancestral co-creation—

It asks for care and regard, it tasks witnessing.

Witnessing is looking diligently [1], not looking away …

To look diligently is an act of love

To record what you see is an act of faith

To share what you record, an act of hope, of possibility

In diligently looking, one can see the enormity of the mining industry in South Africa. The intersections of health, labour, wage theft and the building of an industrial society at the expense of Black people, and the Black men forced into mining, are illuminated through this work. Mining is the site to which Phalafala returns to understand yet another iteration of institutionalised anti-Blackness that, as she writes, renders us as Black people ‘socially dead’:

They persecuted, banished and decapitated our rulers, destroying our governance system, and also criminalised our spiritual practices (Witchcraft Suppression Acts). After the grand theft and savagery by the coloniser, he introduced hut and other taxes that could only be paid with money. This is how the wage labour system was initiated: a bottlenecking of our ancestors into the mines. So this discourse around how mining cannot be considered slavery because the miners chose to work in the mines—elected to do so out of their full agency, and because mining was waged labour—is a false one. The miners were treated as a commodity, as fuel for the machine, their health was never considered, the families they left behind were not only disregarded, but miners’ wives were prohibited from visiting miners in the cities. That form of alienation and deracination, not to mention the permanently looming threat of death, mirrors the slave experience. The stolen land has meant stolen ceremonies and rituals that gave us access to spiritual dimensions necessary for our collective wellbeing. Stolen land is stolen food: we were extracted from the land we lived with and from through subsistence farming, and bottlenecked into supermarkets and fast foods, which are killing us; stolen land is stolen lifeforce, which is fed by both these things—nourishing ancestral foods and ceremonies to mark rites of passage as we move through the world. We the landless remain psychologically and spiritually maimed by this history, socially dead.

The world seems to end many times for Black people and people who have been subjected to settler colonial violence that seeks to eradicate or assimilate. Mine Mine Mine witnesses these ends without making a spectacle of them. The collection is not trying to prove a point or serve as political persuasion. Rather, Mine Mine Mine intimately invites readers to witness the events it documents, and in turn, witness their own lives, and what may be on the other side of the end.

[1] [Footnote by Phalafala:] ‘Diligent looking’ is the methodology of my book Keorapetse Kgositsile & the Black Arts Movement. The book is itself a document of intergenerational song, ancestral continuity, undertaken through witnessing, care and regards. All my work should be read as a constellation of this ethos.

- Kim M Reynolds is an arts and politics writer, a critical media scholar and educator, tech and surveillance researcher, and a human being. Reynolds is primarily concerned with the generative relationship between antagonism and imagination. Visit her website here.