Tan Twan Eng’s third novel, The House of Doors, was longlisted for the Booker Prize, and has just been longlisted for the 2024 Walter Scott Prize for Historical Fiction. He chats to The JRB Editor Jennifer Malec about writing, rewriting, and reverse-engineering.

Tan Twan Eng

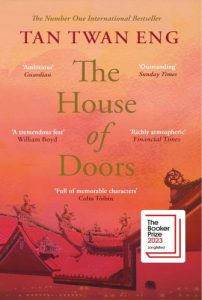

The House of Doors

Canongate, 2023

Jennifer Malec for The JRB: Congratulations on being longlisted for the Walter Scott Prize for Historical Fiction! Which of course you have experience in, having won it in 2013 for The Garden of Evening Mists. What is it that drew you to this genre? What does history mean to you?

I started reading—and reading obsessively—when I was very young. My parents had a very relaxed attitude to what I read. They never restricted my reading, even though I read a lot of books that were certainly too mature for children or teenagers. I never classified whether a book I was reading was historical or contemporary fiction. All I wanted was to be enveloped in the fictional world I was reading.

Now, when I’m writing my novels, I don’t consider them historical fiction at all. To me they’re novels that happen to be set in a certain time period because that’s what the story requires. As a writer I’m trying to recreate the experience I had had as a young boy reading all those books. I want to be lost in the story, especially in the story I’m writing, because if I’m not lost in it myself, how can I expect my readers to be?

Perhaps it’s because a writer has to spend more effort in recreating an authentic and convincing bygone world, that for me, ‘historical’ fiction feels more immersive. For these novels to succeed—in fact, for any novel to succeed—the sense of place and time is essential.

It’s also illuminating and fascinating to see how societies and people have changed over time. In The Gift of Rain I compared Malaya before and during the Japanese Occupation in World War II. In The Garden of Evening Mists I explored how badly traumatised individuals coped after the terrifying years of the war. Novels are all about change: how a protagonist, or a world, changes.

When I was re-reading the first drafts of The House of Doors, I was rather taken aback by what a quietly angry feminist novel it is. It wasn’t intentionally done, but I realised that I can’t write about a woman living in the early nineteen-hundreds without having her knock against the expectations, restrictions and injustices placed upon women by society.

I think there used to be a degree of literary snobbery against ‘historical fiction’, but the Walter Scott Prize has helped immensely in changing that mindset. In the fifteen years since it was founded by the Duke and Duchess of Buccleuch, it has done an invaluable service in drawing the world’s attention to novels that often had been overlooked by the other prizes. It was a great, great honour to have won it in 2013.

More than ever before, it’s essential to know history. So many people in the world—leaders of nations, opinion-makers, politicians—are trying to rewrite the past to suit their own agenda. History is being warped in order to get us all riled up, to sway us and blow us down the path they want us to take. LP Hartley’s novel The Go-Between opens with this sentence: ‘The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.’ Quite so, but we must also know how differently. We must have knowledge of history so we can distinguish what is true and what are lies. If you don’t want to be just another sheep in the flock, start by understanding the past, and go as far back in time as possible.

The JRB: You’ve said that The House of Doors was an extremely difficult book to write, and that you almost gave up on it. I’m so glad you didn’t. But what about this novel made it such a challenge to complete?

Tan Twan Eng: I had planned a big, complex novel for my third book, but then I had to undergo an operation to fix a problematic knee. The recovery process was long and difficult. I couldn’t face the thought of embarking on such a massive writing project, so I put it aside and began what I envisioned would be a smaller novel, one that was easy to write and which would not require extensive research. I was completely wrong.

I lost count of the number of times I rewrote The House of Doors. The story wasn’t working, there were too many confusing strands. It was also complicated to bring the real-life characters, W Somerset Maugham, the Chinese revolutionary Dr Sun Yat-Sen, and Ethel Proudlock, into the story and make it connect and cohere.

People have remarked to me, ‘It must be so much easier writing about a real person—all you have to do is describe them and replicate them on the page.’ But it’s not as simple as that. In fact, it’s much harder. You have to animate them within the confines of all that is known about them, and yet bring something fresh and alive and real to them. You have to make them laugh and weep and hate and love again, long after they have returned to dust.

In addition to those challenges, the directions of my plot had to conform to the personalities and traits of these real-life people. Writing about my own fictional characters felt much less restrictive.

Further problems arose when my editor found the different timelines confusing. I heeded his advice and put in dates and location names in the chapter headings. I’ve never liked these sorts of headings, but to my surprise (and chagrin), this simple insertion cleared up much of the confusion in the story.

He also suggested that I shift two or three scenes to much later in the book so the air wouldn’t be let out of the balloon prematurely. This worked well too. In the end, what I had regarded as insurmountable mountains turned out to be less difficult to scale than I had feared. I also added a number of new scenes—one of those is where Willie goes swimming at night.

Compared to my previous novels, Doors is a quieter, more interior novel—I wanted the surface to be restrained, deceptively placid. As we all know, quiet writing is harder than flashy, noisy writing.

The JRB: The House of Doors is part political history, part illicit love story (stories, to be precise), part biographical and historical fiction, part a study of character, and a love letter to the lush atmosphere of Malaysia; which of these layers did you most enjoy writing?

Tan Twan Eng: I never consider these elements as discrete when I’m writing a novel. I’m more concerned about improving the quality of my writing: how do I create sentences that are original, true and beautiful? And how to make my writing sing?

My favourite part of writing a book is the rewriting. I can spend years doing it, playing with the language in the draft. Every novel I write has to be an improvement over the previous one. Otherwise, what would be the point?

An interviewer once remarked to me, referring to The Gift of Rain and The Garden of Evening Mists, that it must have been difficult writing about war-time cruelty and harrowing violence. ‘On the contrary,’ I replied, ‘I found it quite enjoyable.’ The tension and conflict in that type of scenes make them easy to write. The hard bits are where nothing is happening at all, those banal, connective tissues linking the end of one section to the beginning of a new one. For example, ‘Later that evening, when they gathered on the veranda.’ It’s not easy to shift to the next scene, describe the new setting, the change in mood, the passing of time, and still do so in fresh, striking ways.

At its heart, The House of Doors is about the act of creation: how stories are made, and how they are passed from person to person, from one place to another, and even across time. How do writers turn fact into fiction? And how do they transform fiction into fact?

The JRB: The book centres on the trial of Ethel Proudlock, the first white woman to be charged with murder in Malaya, who claimed that the man she had killed had tried to rape her, but was sentenced to be hanged. What kind of research did you do into the case, and how did you decide what to fictionalise?

Tan Twan Eng: I first read Somerset Maugham’s short story ‘The Letter’ in my teens. Subsequently I discovered that he had based it on Ethel Proudlock’s trial which had taken place in Kuala Lumpur in 1911. ‘The Letter’ made me curious about Ethel. Over the years I read up extensively on her. I suppose even all those years ago I already knew I would write a novel about it.

With The House of Doors, I set out to write my own story of how Maugham came to hear about Ethel Proudlock. I couldn’t find the court transcripts in the National Archives in Malaysia. After much searching, I eventually located them in two places: at the National Archives in Kew in the United Kingdom, and in the National Archives in Singapore. The transcripts were often confusing or had gaps in them—court reporting over a hundred years ago was not as conscientious and detailed as today. It took a lot of my old lawyerly skills to make sense of the transcripts.

‘All novels arise out of the shortcomings of history,’ the poet Novalis wrote. It’s in the gaps and silences of history where I’ve fictionalised the events.

I wanted The House of Doors to be, in a way, a form of reverse-engineering of ‘The Letter’. I hope readers who’ve read Doors will also read ‘The Letter’. I see them as a pair of mirrors, reflecting each other. Reading The House of Doors will affect your reading of ‘The Letter’; this will then alter how you regard the former work, which in turn will recast the way you view the latter short story. And on and on it’ll go. The slightest change in the angle of one mirror will make you question your perception of each work, back and forth, back and forth, until you are unable to distinguish between what is real, and what is fiction.

The JRB: One detail I love in novels is descriptions of trees, partly because I have a deep admiration for people who are able to casually name them, and partly because I find them so evocative. The House of Doors is brimming with this: ‘We joined them in a circle beneath a camelthorn tree, its bare branches spiked with thin white thorns as long as my little finger’, ‘A massive angsana tree, its trunk bristling with ferns, thrust out from the centre of the platform’, coconut trees ‘like sea anemones waving in the current’. Are you someone who knows the name of trees?

Tan Twan Eng: I’m not well-versed in the names of flora, but particularising them gives a feeling of verisimilitude to any writing—it makes the setting feel more immediate to the reader. On my evening walks I try to learn about the names of trees and plants and flowers I come across, and the names of birds and other animals. Even when I’m not at my desk, the writing is happening all the time: I’m always trying out phrases and descriptions based on what catches my attention, or storing away trivia for future use.

With each book it gets harder and harder to come up with descriptions of nature that are lyrical yet original, descriptions that are so accurate and striking that there’s an explosion, not merely in the mind, but also in the heart. ‘Yes! That is exactly what a spider web looks like! Why hasn’t anyone else described it like that before?’

The reader must feel the mood of the characters and the atmosphere of the setting. I deploy every technique in my arsenal to place the reader in the heart of the scene: smells, hearing, sight, touch, and also, more powerfully, the allusions and resonances created by my choices of words which I hope will set the bells ringing in the reader’s mind. I don’t want to tell my reader what to feel; I want to make them feel.

The JRB: Maugham was one of the most famous and acclaimed writers of his day—at one point you have him proclaim: ‘We will be remembered through our stories’—but he has since faded into relative obscurity. What attracted you to his work, and why do you think his star has waned in the contemporary moment?

Tan Twan Eng: Maugham’s not the world-famous writer that he once was, true, but many bookshops in England—and in cities around the world—still carry his more well-known titles. One of his best novels, The Painted Veil, was adapted into a film starring Edward Norton and Naomi Watts a few years ago.

On my book tours in the UK and America to promote Doors, I was extremely gratified by the many people who told me that they’re still reading Maugham’s works. In his review of Doors in The Guardian, Xan Brooks made the very pertinent statement: ‘Somerset Maugham, who is out of fashion, but never out of print.’

Maugham was one of the most fascinating figures of the twentieth century. When he first started travelling it was on steamships, and he lived long enough to travel on jet planes. He had lived such a long life that he had seen the world —its attitudes and its moralities—change so considerably.

Somerset Maugham’s writing and his stories will endure. He didn’t cling desperately by his fingertips onto the overcrowded bandwagon of the latest trendy issues of the day; instead he wrote about human nature—and human nature is timeless.

The JRB: A bit of marginalia, if you don’t mind indulging me: ‘The Letter’ was first published in the short story collection The Casuarina Tree. Was the casuarina tree that was so significant in your debut novel The Gift of Rain a nod to Maugham, perhaps a throw-forward to this book?

Tan Twan Eng: Those trees are a common sight on the beaches of Penang, so I wasn’t trying to do a throw-forward to Doors. But there are a number of call-backs to my first two novels in Doors. The books are set in that same world, and their timelines overlap. I felt it would be natural for them to have these small connections, creating echoes and resonances between my books. I knew my long-term and sharp-eyed fans would enjoy discovering these links. Some of the connections are obvious, but there are also several of them that are more subtle and cunning. And of course there are also call-backs to Maugham’s stories. These literary easter-eggs make the characters and the stories in the book feel like they’re a part of a larger world beyond the boundaries of the page.

The anecdote about the casuarina tree in Doors, how it whispers secrets to the listener, I found in Maugham’s preface in, where else, The Casuarina Tree, his collection of stories. When I first read it I wondered, ‘Where did he hear that from?’ When I was writing Doors I decided to have some fun by letting Lesley tell it to him. I enjoy the idea of how stories travel around in loops. We’re all echoes of other echoes.

The JRB: Maugham had no qualms about featuring real people and real events in his stories, even, as you point out in the novel, using their real names when the inclination took him. What do you think he would have made of your depiction of him?

Tan Twan Eng: I’m confident that I’ve been balanced and objective in my depiction of Maugham. I’ve depicted him as he was, the man and the writer, in all his strengths and his weaknesses, in his self-assurance and his insecurities, his pettiness and his generosity of spirit. I would have loved to have known him. The closest I’ve come to that was when I was contacted by Maugham’s great-granddaughter last year. She told me that she and her mother, Maugham’s granddaughter, Camilla, had enjoyed Doors, and thanked me for writing about him. We met for drinks at Camilla’s flat in London one rainy evening. It was a privilege to hear her talk about her grandfather and the holidays she and her brother used to spend at Villa Mauresque, his home in Cap Ferrat. Many of us have this image of Maugham as a misanthropic and difficult old man, but Camilla revealed to me that he was a warm and loving grandfather. It was a very convivial and enlightening evening I spent with Maugham’s granddaughter and great-granddaughter. I will always treasure the memory.

The JRB: Being so immersed in his world, did you feel Maugham intruding or pushing his way into your manner of writing?

Tan Twan Eng: Initially I wrote Maugham’s chapters in his style and voice. I had read his books so many times; I had studied how he spoke and moved in archival videos and interviews online. After a few chapters, however, I sensed the book wasn’t coming alive. The problem, I realised, was that I was creating a marionette of Maugham. Once I abandoned that technique he came to life for me.

I’m a great fan of Maugham and his writing, and I was determined to be faithful to his personality and characteristics, but I had to be alert that I wasn’t unwittingly writing a pastiche of Maugham. I enjoyed writing about him—I could incorporate many of my experiences as a writer—the joys and the frustrations of a writer’s life, at the desk and away from it—into the novel.

The JRB: The novel is set in colonial Malaya in the early nineteen-hundreds, and of the many things I love about it, your ability to inhabit that time so comfortably is perhaps its most impressive. How do you manage it? Do you immerse yourself in the fiction of the time? Non-fiction? Or do you have a time machine?

Tan Twan Eng: I have a time machine. Joking aside, one of the most challenging aspects of writing about the past is just how easy it is to slide into the trap of judging it through our modern lenses. Easy, tempting, and utterly lazy. I had to be vigilant that I was not imposing, even subconsciously, modern values into my re-creation of nineteen-hundreds Malaya. Everything I wrote had to be of that era: the language, the words, the phrases, the slang, the cultural references, the attitudes.

Biographies and diaries from that era were more useful than fiction for my research, as were old photographs and postcards. History is so massive and unwieldy that it’s daunting to try and sculpt it into manageable blocks, but I’ve learned that very often it’s in the footnotes of books where I stumble upon the most fascinating and odd facts. They’re often my entry-point into a story I’m trying to tell: the footnotes of history.

The JRB: I was somewhat amused, and also unnerved, to see a review of The House of Doors that pronounced that it presented a ‘refreshingly balanced view of empire’. Other reviewers have made a point to call attention to the fact that the novel is narrated by ‘the voice of the oppressor’. (For what it’s worth, for me your treatment of the colonial aspects of the novel is deft, complex, scathing, elegant.) Do you contemplate or anticipate these readings of your work?

Tan Twan Eng: It’s a fair and accurate statement. I used to be a lawyer, and a lawyer is trained to be objective, to look at everything from all angles. They say there are two sides to a coin, but there are actually three sides: the edge of the coin is another side, isn’t it?

As for the comment that I’m writing in ‘the voice of the oppressor’—it seems implicit in those words that I should not be doing so. It also comes across as highly condescending. I’d like to ask, ‘Why not?’ and ‘Who are you to tell me how I should write?’ Whatever happened to creative imagination and artistic freedom? As a writer, my primary focus is on how best to tell the story I want to tell, and if that story works most effectively, powerfully and authentically from a particular narrative point of view, then that’s all there is to it. Finish and klaar, as South Africans say.

Ultimately, I don’t tie myself in knots over these issues when I’m writing. My focus is on the quality of my writing: I have to ensure that it’s original, evocative and free from cliches. Lazy writing enrages me. I’ve mentioned this before at literary festivals. From the very start of my writing career there’s been one overarching aim: to create works that are not timely, but timeless. Thousands of books are published every year. How many of them will be read, or even remembered, in ten or five years time? Or even two years time?

The JRB: While I was reading The House of Doors, I went down quite a few rabbit holes into Chinese history—Hong Siu Chuan and the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom, Sun Yat Sen and the Revive China Society, the significance of the queue hairstyle. As a historical novelist, what’s your tactic for wearing your research and reading—which must be extensive—lightly in your writing?

Tan Twan Eng: The temptation is always to throw every morsel of information, detail, trivia and anecdote I’ve spent years collecting into my novel. I had to develop the instinct and the capability to recognise when less is best. It’s a balancing act, especially if I’m writing about subjects which are not so familiar to readers in other parts of the world—those subjects you mentioned are illuminative.

One way to solve this is to have a character who is unaware of a historical fact you want to bring in. Another method is to bring to the reader’s attention some feature or mannerism that was an anomaly for its time: as an example, in Doors, Lesley wonders why Dr Sun Yat Sen, who is Chinese, isn’t wearing his hair in a queue, the long braid that was made compulsory by the Chinese emperors. I have to be subtle and imaginative to weave my research into the fabric of the tale, so that it forms a part of the overall pattern.

Speaking of Dr Sun Yat Sen, most people in Asia know who he was and the huge impact he made on China’s history. But initially I only became interested in him because, when I was a boy, my father used to tell me that he grew up just a few doors away from the former Penang headquarters of Dr Sun’s political party.

The JRB: When nationalistic feelings overcome me (it happens to the best of us) I unashamedly claim you as at least partly ‘one of ours’: a South African writer. So the sections of the book set in the Karoo, although brief, delighted me. What were your reasons for relocating Robert and Lesley to South Africa? Familiarity? Or fondness, perhaps?

Tan Twan Eng: The Karoo is not one of my favourite places at all, I must confess. Like Lesley Hamlyn, I ‘ache for the monsoon skies of the equator, for the ever-changing tints of its chameleon sea.’ But I understand the appeal of the Karoo for some people: it sandblasts away all vanities and trivial concerns that clog up our daily lives.

The reason for choosing the Karoo, like many reasons in any literary work, was very prosaic: Robert had to move to a dry environment for his health, and I needed Lesley to be cut off from the rest of the world, to disappear and—one of her great fears—to be forgotten. What better place than the Karoo?

The JRB: Have you returned to the book you were writing before you began The House of Doors? Or, the dreaded question, which I feel as a big fan I simply have to ask, what are you working on next?

Tan Twan Eng: I have, actually. But I never talk about the book I’m working on. I feel it’s like describing a dish you’re planning to cook. I would rather savour the dish when it’s cooked than to hear it talked about at length.

The JRB: Finally, since writers tend to be readers, I like to ask writers what they’ve been reading. Are there any books on your bedside table or on your desk at the moment that you’d recommend?

Tan Twan Eng: Tenderness by Alison MacLeod—it’s about DH Lawrence and his struggles to write Lady Chatterley’s Lover. The Mirror and The Road: Conversations with William Boyd, edited by Alistair Owen. A series of interviews with Boyd, about his works and his life. Stand By Me by Wendell Berry. A recent discovery for me. Beautifully written short stories spanning the century, linked to each other by people and the small farming community they live in. Henry ‘Chips’ Channon: The Diaries 1938—1943. The third volume of diaries from one of the greatest name-droppers of twentieth century history. Chips Channon had met everyone who was worth knowing in British high society—politicians, aristocrats, artists, writers—and wrote about them in his diaries with brutal candour, humour and bitchiness. Imperial Twilight by Stephen R Platt. An engaging and fascinating book about the Opium War in China in the early nineteenth century. A Bite of the Apple by Lennie Goodings. Lennie interviewed me (and was superb) at the Bath Literary Festival last year. She’s the chair of Virago Press, and this book is about her decades working there.

- Jennifer Malec is the Editor. Follow her on Twitter.

An extremely stimulating and thought-provoking interview. One to keep and refer to again. Essential reading for any writer.

Eng’s reply to the question about his next book reminded me of DJ Opperman’s answer when asked a similar question: “Ek praat nie oor brood wat in die oond is nie.”