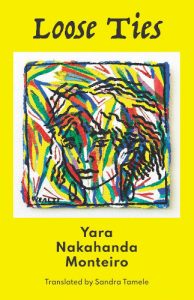

The JRB presents an excerpt from Yara Nakahanda Monteiro’s novel Loose Ties, translated from the Portuguese by Sandy Tamele, which was recently longlisted for the Dublin Literary Award—the world’s richest annual literary prize.

Loose Ties

Yara Nakahanda Monteiro (translated by Sandy Tamele)

Paivapo Publishers, 2021

Read the excerpt:

1.

Her very first memory is a tree; the second, a wave. Without casting a shadow, she flies through the roots bearing the bottom of the sea. She doesn’t exist prior to that moment, or beyond it. These are images that burst into her dreams and terrorise her sleep.

From time to time, whiffs of the intense aroma of sour milk emerge. Then the taste of sweat, salty, that lingers on her tongue. Part of her finds comfort in such sensations. The other part is disturbed by the emptiness they bring, these are the only memories she has left of her mother. The most intimate truth is to not be able to claim her mother as hers. She knows that. Rosa Chitula, her mother, loved Angola more than she loved her daughter and fought for the country.

Her name is Vitória Queiroz da Fonseca.

She is a woman.

She is black.

2.

The first child of Elisa Valente Pacheco Queiroz da Fonseca and António Queiroz da Fonseca was born on 31 March, 1944. Honouring her two grandmothers, she was baptised as Rosa Chitula.

A strong personality, Rosa was always averse to discipline. Her rebellious spirit got her expelled from the Madres de Silva Porto College. António knew that his daughter was a tough cookie, and to his dissatisfaction, she disliked home living or household chores. The more her father tried to lock her in, the more she rebelled. Until he, António, gave up.

To keep her under his eye during his runs to the coffee fields, to the cattle farm or to the store, he began to take her along with him. It was in those shared moments that they grew closer.

Little by little, the father started to entrust to his daughter small responsibilities in the management of his businesses. After a while, Rosa was giving orders to the workers. Other than respect for his daughter, António suspected that the workers feared the gun Rosa flaunted unashamedly. The clothes, and the way she wore her hair tied under the hat hid her delicate facial features. Rosa resembled an energetic, mixed race young man so that even her father sometimes mistook her for one.

As time went on, António was certain his decision to get his daughter involved in the business of the farm was a wise one. Or at least he thought it until the dawn of the Sixties, a time of radical ideas and ideals.

In Luanda, reactionary groups instigated the population to a protest. Despite the initial attempts of the central government to muffle the rumours, they spread faster than gazelles throughout the country. António saw himself as an assimilado and above all, as Portuguese. He viewed the implosion of nationalism as an insidious twist against the colonial serenity. He was shocked by Portugal’s attitude of washing their hands off it all. It seemed to him that they did not know how to solve the big, ensuing maka.

Rosa, had always been a free spirit and now her rebellious nature found a cause. Her insurrection to imperialism began to grow stronger as the radio and newspapers refused to ignore the disordinate looting, the rapes, kidnappings and escalating tension between whites and blacks.

The family was dining when Rosa first questioned her father about the payment of wages to natives.

‘Who are those blacks who have these communist ideas?’ António responded in a menacing tone, punching the table.

The discussion ended right there, but it was enough to make António more watchful of his daughter.

Seek and you shall find. All it took was a short, but sure step for António to get to the truth. He broke his routine and, without telling anyone, he decided to stay home one morning. Under his daughter’s mattress he found pamphlets. After showing them to his wife and blaming her for Rosa’s bad principles, he destroyed the pamphlets. He thought it was best to avoid an argument and said nothing to his daughter.

Love makes us a little short-sighted. António ignored his daughter’s behaviour until the moment it became the talk of the café tables in the club.

‘They haven’t done anything because she is your daughter, but the day will come when they’ll have no choice,’ they warned him.

The domestic problem had turned into public shame, and Caculeto, António’s faithful lieutenant, was instructed to watch Rosa closely and report back to his boss. It was already too late.

The Saturday of the same week that António had overheard criticism of Rosa at the club, he was finishing his meal of maize with mushrooms in his office when Caculeto knocked on the open door to speak with the boss. Under his arm, he had a newspaper. From his employee’s agitation, António could sense the seriousness and urgency of the matter. He put his knife and fork down and told him to come in. Caculeto, too afraid to just hand the newspaper to his boss, stood at the door. He opened the newspaper on page eight and due to his nerves, read the title written in block capitals PEACEFUL PROTEST AGAINST THE COLONIAL REGIME.

He was about to start narrating the article when António stood up and snatched the paper, ‘Give me that. I know how to read,’ he asserted.

Shock dismembered the patriarch’s reasoning. Under the header of the news, there was a photograph of the demonstration.

Rosa, his daughter, was in the first row of the protest and was brandishing a poster reading ANGOLA FOR THE ANGOLANS.

‘The daughter of the assimilado being used as the flagship of revolt,’ acknowledged grandpa. Anger blinded him. He was brandishing his belt before he had even reached the veranda of the house. His wife and other daughters tried to stop him without luck.

Rosa vanished on the very day of the beating. She didn’t come back, and her father didn’t go looking for her.

A few months later, the colonial war broke out. The urban resistance had already managed to spread militia all over the country thus beginning the barbarianism in the nation. Heads were severed from bodies, the wombs of women were ripped open and children, mutilated. They massacred anyone who did not want to join the revolt.

Before the rainy season, the family, together with the domestic workers, fled from Silva Porto leaving behind burning crops, loose livestock and whatever they could not take with them.

As soon as they arrived in Nova Lisboa, today the city of Huambo, António met with the governor, farmers and assimilado traders. Their opinion was unanimous. The wick of war had already been lit. They all feared for their lives and their estates. In Luanda, entire families had already begun to flee to Lisbon. Even then, António believed that good fortune would be on his side and decided to carry on the business at his shops and trucks as he always had in his old home.

He turned misfortune into an opportunity. He worked with both sides of the political conflict and intended to continue doing so as long as providence kept his secret. His mixed race had put him in a halfway position. To some, he was not black enough and, to others, he needed to whiten his skin. He adored the Portuguese and tolerated the others. Both whites and blacks treated him with grudging respect for his ability to engage in both worlds so easily.

~~~

Yara Nakahanda Monteiro is an Angolan writer. Her debut novel, Essa dama bate bué! (2018), has been translated into several languages and is studied at universities all over the world. In 2022, Monteiro won the Glória de Sant’Anna Literary Prize for her decolonial, ecofeminist poetry book Memórias, Aparições, Arritmias. Monteiro has co-written two short films, Path to the Stars and The Island, both counter-narratives to Angola and Portugal’s colonial past. Her short stories and poetry have been published in various magazines, including Granta and Revista Pessoa. She is a curator for radio and podcasts, and a regular guest at universities to talk about feminism, Afro-European identities and narratives. She graduated in Human Resources and worked in the area for fifteen years in fields such Diversity and Inclusion and Talent Management. In her words: she is a great-granddaughter of slavery, great-granddaughter of miscegenation, granddaughter of independence and daughter of the diaspora.

~~~

Publisher information

A few weeks before her wedding, Angolan-born, Portugal-residing Vitória is a runaway bride back to an Angola she has no memory of.

Desperate to connect with the mother she never knew, she establishes her base for her search at the home of a family friend who, with her twin daughters, introduces her to the three Luandas. A Luanda for the rich and powerful who are above the rules. Another Luanda for the aspirational middle-class who are flattered by any proximity to the rich and powerful. And yet another for the povo doing what they can to eke out a living in a city that sees them but chooses to ignore them.

And what does the commanding, over-cologned, poetry-reciting General Zacarias Vindu know about her mother, a former independence cadre? A radio announcement in the presence of a new friend will lead her from Luanda to Huambo where her journey will take unexpected turns and where her questions are answered. Will the answers be to her satisfaction?

Yara Nakahanda Monteiro’s Loose Ties is a lyrical narrative of sisterhood, loss and humans’ eternal quest for love and acceptance.