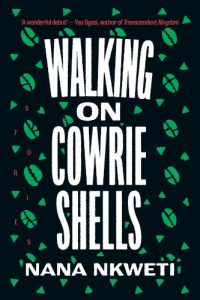

The JRB presents an extract from ‘It Just Kills You Inside’, excerpted from Walking on Cowrie Shells, the debut short story collection from Caine Prize finalist Nana Nkweti.

Walking on Cowrie Shells

Nana Nkweti

The Indigo Press, 2022

It Just Kills You Inside

(Based on True Events)

Boogeymen are real in Africa, folks. Both the real ones and the sticky crude imaginings that ooze up from the darkest of hearts. They are gold-epauletted military despots who disappear your loved ones in that bump of the night. Or Big Pharma execs donating untried and untrue drugs to guinea pig villagers for tax write-offs. And then there are the workaday nightmares that complicate waking life, come courtesy of the tribalist, the spiritualist, the herbalist. This is why the first reports were dismissed as so much hinterland superstition, bush whispers in the dusk. This was Africa after all—the land of juju, obeah, and kamuti. A place where death rides in from the desert on horseback.

With all these familiar horrors, who in the hell was going to believe in zombies?

No one, for a very long while, when yours truly was on the job. You see, tropical governments hire outfits like mine for their cover-ups. I am what some might call a ‘fixer.’ My specialty: crisis management and communications—coming in after that burst oil pipeline wrecked the endangered ecosystem of some tree hugger’s wet dreams or after your company’s homicidal aspirin spree-killed dozens, tamper-proof seals about as secure as a buck-toothed virgin on prom night. I’m the man who got that sensitive CEO in front of the cameras, contrite and doling out ‘heartfelt’ assurances about maximizing safety measures and thorough reexaminations of system protocols. Even better, I trained him to cry on cue—one muscular, robust tear, of course, all manly like.

There was a lot at stake back then: a good name, millions in foreign currency, political capital worth its weight in bullion. What was a few hundred thou between my kleptocrat buddies and me for a tidy little media campaign that whitewashed the first zombie death tolls? I’d said yes before I even believed them. So used to the garden variety brushfires of their regimes—political purges, coups d’état, ethnic cleansings—that I all too easily dismissed the Z word as complete crapola.

Were they really trying to bullshit a bullshitter? Don’t piss on my leg and tell me it’s raining. Insulted, I hiked up my retainer. Resolved to get to the what’s what of things when I got to ground zero in Cameroon.

• • •

Twenty-odd years ago, in the badlands and bedlam days, French scientists had been flown into Cameroon on the hush for research support. Their government always did take a special, mostly mercenary, shine to their former colonies. The country was one of several puppet regimes they propped up in the region. I was flown in to whittle down their science jargon into reassuring sound-bite-sized pieces and forestall any community hissy fits with PR pabulum.

There had been a lab-coated Frenchman, a Dr Georges Orliac, a head honcho at the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, Paris offices. He was flanked by a retinue of bespectacled suits and coats, quickly introduced, quickly forgotten, all looking at me expectantly. But first they gave me some papers to sign, ‘eyes only, confidential’ type stuff. Standard for most of my clientele but somehow there seemed to be more emphasis on this ink, more jittery eyeballing of this particular John Hancock.

‘You know about Lake Nyos, Monsieur Connor?’ Orliac was fidgeting with his glasses.

‘’Course,’ I said. ‘Summer of ’86. Nearly two thousand dead. Natural disaster, bucolic lake goes acidic, belches up a cloud of CO2 gas that asphyxiates villagers for miles ’round. Takes out their livestock, too.’

‘Oui, oui. And about the Israelis?’

Yeah, I had heard, rumors of secret Yehuda bomb sites, conspiracy theories that confounded even me, King of Misinformation. A lake goes kaboom and suddenly it’s an international plot; talk of government payoffs allowing nuclear tests in subterranean lairs was bolstered by the Israeli prime minister’s immediate in-country presence, swooping in with a fully equipped hospital plane just days after the disaster.

‘I know some,’ I replied. In my business, information sharing was a game of hide-and-seek or keep-away.

‘The rumors are true,’ he said. ‘The Israeli military was testing a neutron bomb; that is what detonated the gas.’

I was quiet a spell, studying on it. I’d heard my own rumors. More likely, the French had done this themselves, broken a beaker or two of something heinous, and now were on to the slapdash ass-covering phase of the project. Either way, I was on the job. Orliac thrust a stack of photos at me—exhibit As and Bs and such.

‘What you are looking at are the villages of Sobum, Chah, Koshing, and Nyos,’ he said. ‘Fertile lands, barren now. We have been studying and treating the survivors of the disaster … getting the usual complaints: heartburn, lesions, and neurological problems like monoplegia, forgive me, muscle paralysis to one part of the body. You follow?’

I nodded. ‘This is all well and good, Doc, but why am I here? Nyos was in ’86, five years ago, ancient history.’

‘You are here because there were other survivors besides the living.’ He searched my face for some reassurance that he should proceed. ‘The dead, those who succumbed to the initial gas cloud—some buried, then some, some we kept, set aside for study—they rose.’

They rose? They resurrected? Yeah, right. Was he really trying to bullshit a bullshitter?

I was in his face then. Giving him a shake. Mussing up his crisp lapels. ‘That’s the craziest thing I ever laid ears on, Doc.’

He was rattled, then he rallied. His fervent gaze settling on me with all the might and will and smiting force of a true believer. Doubting Thomas that I was, I couldn’t quite put my faith in the good doctor’s pronouncements. I was a practical man who needed hard facts and real-world answers—not hokum, not hoodoo. I wanted out of that peculiar revival tent, was walking out of the room when the doctor said, ‘Look.’ That was all he said.

Four minutes later, I did. Got blue in the face.

‘Christ-al-mighty,’ I whispered, then loudly, ‘what the hell have you boys gone and done?’

~~~

- Nana Nkweti is a Cameroonian-American writer, Caine Prize finalist, and graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. Her writing has been published in journals and magazines such as Brittle Paper, New Orleans Review, and The Baffler, among others. She is a professor of English at the University of Alabama.

~~~

Publisher information

A virtuosic debut collection that roves across genres and styles, by a finalist for the Caine Prize.

Shortlisted for the 2022 William Saroyan International Prize for Writing.

In her powerful, genre-bending debut story collection, Nana Nkweti’s virtuosity is on full display as she mixes deft realism with clever inversions of genre. In the Caine Prize finalist story ‘It Takes a Village, Some Say’, she skewers racial prejudice and the practice of international adoption, delivering a sly tale about a teenage girl who leverages her adoptive parents to fast-track her fortunes. In ‘The Devil Is a Liar’ a pregnant pastor’s wife struggles with the collision of Western Christianity and her mother’s traditional Cameroonian belief system as she worries about her unborn child.

In other stories, Nkweti vaults past realism, upending genre expectations in a satirical romp about a jaded PR professional trying to spin a zombie outbreak in West Africa, and in a mermaid tale about a Mami Wata who forgoes her power by remaining faithful to a fisherman she loves. In between these two ends of the spectrum there’s everything from an aspiring graphic novelist at a comic con, to a murder investigation driven by statistics, to a story organised by the changing hairstyles of the main character.

Pulling from mystery, horror, realism, myth, and graphic novels, Nkweti showcases the complexity and vibrance of characters whose lives span Cameroonian and American cultures. A dazzling, inventive debut, Walking on Cowrie Shells announces the arrival of a superlative new voice.

‘These genre-leaping stories are funny and heartbreaking and wonderfully ferocious; it’s been ages since I’ve read sentences with this much verve and snap. Walking on Cowrie Shells is a delightful, rollicking debut.’—Carmen Maria Machado, author of In the Dream House

‘Nana Nkweti’s exuberant collection is full of stories that weave together love and friendship, horror and comedy, all with great deftness. The characters, straddling continents and cultures, carving out a place for themselves, remind me of home. A wonderful debut.’—Yaa Gyasi, author of Transcendent Kingdom and Homegoing