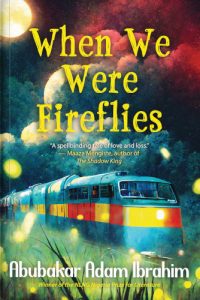

The JRB presents an excerpt from When We Were Fireflies, the forthcoming novel from acclaimed author Abubakar Adam Ibrahim.

When We Were Fireflies

Abubakar Adam Ibrahim

Masobe Books, 2023

Leaf Storm

Yarima Lalo was standing by the window looking out into the street where a whirlwind was making a spiral of dead leaves dance on the asphalt. The dying twister slammed a handful of leaves against the front of his studio, pressing a eucalyptus leaf from a nearby tree on the pane. He studied the venation of the leaf as if it were a creature crawling up from the depths of his fantasy, or nightmare, to torment him. Long dead, long dried, the leaf lingered before yielding to the breeze that carried it off.

Shaking his head, Lalo crossed over and latched the glass door but the dust had already stolen in, bearing the earthy scent of petrichor and a sense of foreboding. He could tell something else was coming, something he could not name.

Outside, the storm invoked chaos—shop owners closed their doors, awnings billowed, the red parasol of a recharge card seller across the street toppled over and hurtled away. The woman chased it. A turtle-shaped cyclist sped by, the front of his green kaftan pressed against his chest, the air-filled back ballooned like a shell. A woman battled to keep her wrapper, a blur of yellow and blue, and her dignity, both of which the storm seemed intent on snatching. A man ran after his embroidered cap, his wind-filled jellabiya bloating. Lalo had recollections of playing in pre-rain wind storms as a child. Of chasing dust devils with a bowl, trying to trap the infant djinns twirling within them. Of ignoring their mothers’ strident voices dissuading them from messing with demons and other mischievous super-naturals. Of chanting Allah kawo ruwa da kifi soyayye, their voices crisp and enthusiastic, singing with gusto and staunch faith that fried fish would actually fall from the heavens. He did not remember the faces or the names of these children he played with. Nor did he remember from which of his lives these memories came. Yet, in the weeks since his encounter with the train, his resurgent memories of previous lives and his worry over them have grown a moderate bush of beard on his face and cast a pall over his heart.

Clunky raindrops struck the panes and Lalo recoiled from them. Taking a step back, he watched them morph into splatters that lazed on the glass before trickling down. Surprised at how his body quivered, he fetched a feather duster from a drawer by the window and attacked the dust that had coated his paintings, laced themselves into the canvas and embedded themselves into the nooks of the frames. He worked with fervour, twisting the duster, rolling the handle between thumb and index finger, stroking the corners of the frames with it. As if by beating away the dust, he could disperse the image in his mind of a body in a cornfield as the rain fell. The harder he tried, the more forceful the image became, until he stopped, shut his eyes and ran his hand over his beard. He sighed and opened his eyes. Pangs of hunger nibbled at him. He wished he had his lunch before the rains came. Now he had no idea how long he had to wait.

Looking up at the clock, his heart lurched. 2:14. It was the same time he had, in recent weeks, been waking up from the nightmares that had coloured his sleep, with splashes of blood, gore and recently unearthed memories of love and loss. The same time in wakefulness that his heart would clench three times, every day since the train.

The rattling door startled him. Through the glass, a woman gestured with two open palms, pointing sky-wards and bringing her palms together in a solemn appeal. Her shoulders were unevenly wet; the front of her blouse had already flattened itself against her bosom. She was young. Her facial features—large eyes, silky eyebrows clinging to wet skin, and a finely-shaped nose adorned with a nose stud—struck him as alluring. And the dress, flushed coral and black, moulding itself to her svelte frame reminded him of happy season—blooming trees and flower strewn streets. He feared she might catch a cold being soaked like that. Yet, his heart clenched. She could be trouble for him. Lalo turned back to his paintings. He hoped she would be gone by the time he turned back to the door. But she was still there, purse held over her head, her expression asking why he was reluctant to help, shocked, even that he would not. Just as he was turning to his painting, it struck him that he had seen those eyes before—large luminous, filled with childlike glee—that day at the train station. The nose stud had thrown him off. She hadn’t had it then and her looks had been affected by her make up. He swivelled back only to find her gone.

An inky explosion of guilt spread across his heart, colonising it like a guileless country, making his chest contract, hurting. He hurried, opened the door and was relieved to find her tucked into an alcove of the building next to the studio, back pressed against the wall. Her head was out of the rain but her rhinestone-embellished silver shoes were getting drenched. If the breeze changed direction, she would be bathed in the spray. He gestured for her to come in.

‘Thank you.’ She sounded a tad irritated as she walked past him while he held the door. ‘I’m sorry. I thought I could make it to the supermarket before the rain came. I actually wasn’t expecting the rain so soon.’

He smiled, remembering with fondness how she made her words chase each other. He had hoped he would see her again but in the last few weeks, his mind had been concerned with other things. His mind was concerned with other things at that moment. He kept his gaze on her heels, which made her almost as tall as he was, taller than he remembered, as they clip-clopped on the tiles until she stopped by the window where he had been standing minutes before, and looked out to the street. She paced, as if she could reach out and wave the rains away.

‘The supermarket is not far. But being soaked by this rain will not be good for you. If you are in a hurry though I think I have an umbrella here somewhere.’ He wondered if he should go ahead and search for one a client had forgotten weeks before. It was somewhere in the clutter of the tiny store he kept his rolls of canvas, frames, paintbrushes and paint-splotched work cloth in.

‘I am just recovering from a cold,’ she said, whipping out her phone from her purse. ‘I don’t want my head exposed to the rain.’

‘Stay as long as is necessary.’ Something about her unsettled him; she was somehow both appealing and sinister, dangerous even. But deep down he knew what bothered him about her was his own insecurities and reservations.

‘I think I should leave,’ she said, looking up from scrolling through her phone. ‘Sorry to have troubled you.’

‘But it’s still raining.’ He looked out the glass panel on the door. From the grey blanket overhead, a steady shower fell. Rivulets formed on the street and slipped into the drainage. A streak of angry white light, in the shape of a tortured ‘Y’ forked across the bleak sky. Lalo counted under his breath and on ten, thunder rumbled. ‘I did not recognise you at first,’ he said. ‘You are the woman. From the train station,’ he said.

She turned to him with a questioning expression.

‘The day of the test run,’ he said. ‘You asked me for the time.’

She frowned for an instant and perhaps saw him, really looked at him, for the first time. When her eyes travelled down to his shoes, a light popped into them and a smile broke across her face. ‘Oh! I remember. You are the snakeskin Sancho guy!’ Her hands flew to her mouth. ‘That’s how I remember you. I did ask you for time indeed.’

He looked down at the snakeskin patterns on his shoes, their brown almost matching the tiles. He had not always loved these shoes. He did not like looking like a lost cowboy but he loved them then, loved how they made him feel—loved. Loved the way they let him swivel on his heels.

‘2:14, same time you knocked on my door today,’ he said.

‘So, I guess no point asking you now what time it is.’ Her laughter tinkled. ‘How strange though! What a coincidence!’

‘Is it?’ He smiled. He liked that she was laughing. He liked how she laughed—a jarring high-pitched laughter that was without restraint or pretence. It wasn’t pleasant or matched the allure of her looks, it was just loud and unbridled, like free birds fluttering away. He wished he could laugh freely like that.

She smiled too. ‘You look different, moodier maybe. And you have grown a beard.’

Lalo caressed his beard as if to be sure it was there. Her directness made him smile.

‘Sorry, I am a bit too forward sometimes,’ she said tilting her head as she smiled and then almost in the same breath added, ‘and you still have the same shoes on. Gifts from your mother, you said.’

‘You remember.’

‘Of course. I thought it was cute. A man who wears shoes like that to commemorate his mother has to be adorable. I liked that,’ she cleared her throat coyly. ‘You don’t see shoes like that every day. Your mother has … peculiar taste.’

He had never used the word adorable to describe himself. He thought it was funny she would use it. Adorable was a term he associated with stuffed toys and little children. Not a bearded grown man who had worked most of his life, built his physique and his mind, to escape these connotations of feebleness. ‘I know. I didn’t like them at first. Not something I would have chosen for myself. But now they mean everything.’

‘Your mother is not …’ she could not bring herself to utter the words.

‘No, no,’ he said. ‘She is very much around. Just asleep. She has a condition. She sleeps for weeks at a time.’

She stopped laughing when she realised he was serious. ‘Oh, I’m sorry. I thought it was a joke.’

‘It’s okay. Not many people understand. One day she was fine, then she went to bed and didn’t wake up for days. It has happened a few times now. When she sleeps, these shoes, they feel like the only connection I have with her, something of hers I can carry with me everywhere.’

Her eyes clouding over, she looked down at the shoes and placed one palm over her heart. When she spoke, her voice had a slight tremor. ‘I’m sorry to hear that. I hope she gets better.’

He mumbled an ameen.

An awkward silence, like weeds, sprouted between them. In the time it took for that silence to take root, and break the surface, she reached for her phone again—scrolling through it. Lalo sensed that her gaze was avoiding his, and that the hint of sadness he had caught in her voice could be found in her eyes if he looked.

‘Do you live nearby?’ he asked. ‘I think I have seen you a few times strolling by.’

‘Oh, not really. I have a henna parlour down the road on Ademola Adetokunbo. And I like walking a lot. This damned city is not built for walking,’ she said.

‘Tell me about it. One of the things I miss about Jos. I lived there once. Used to walk everywhere to see my friends,’ he said. He placed two fingers on the glass pane and mimicked a walking motion. ‘Sometimes I think of painting the walkways of Abuja. Every stone a different colour. It won’t take a lot considering.’

‘That’s a crazy idea. Would give this place some character and probably land you in jail.’

Lalo laughed.

‘Well, then,’ she looked around the studio. ‘Since I’m not a stranger, aren’t you going to offer me a seat?’

He gestured to his table at the back, away from the framed paintings lined up against the wall. It struck him then how small his studio was, or rather, how cluttered it had become. On the white walls, the vivid colours of his works stood out. Beneath that wall, a cluster of some of his older works were lined. He had painted more than he had sold in the last few weeks, since the train. His new phase, birthed from a feverish haze, was done for himself. These paintings were manifestations, fragments of memories he captured for himself and did not care if anyone offered to buy them.

She crossed the studio and sat down on a high wooden stool by the window. From her purse, she pulled a handkerchief, used a corner to dab at her eyes and then wiped her shoes. Then she resumed scrolling through her phone.

Lalo stepped away from the glass, from the rains, to his workspace. His fingers trembled as he attempted to mount a canvas on an easel. Two tries later, he sat on the edge of the table studying the blank cloth, willing it to inspire him, for images to morph out of the fabric and whisper to him, but all he could visualise was a body in the cornfield being drenched by rain.

His phone which was sitting on the table rang, a shrill polyphonic sound that made her sit up. Lalo crossed the studio and pressed the phone to his ears. It was Chioma, the curator. He spent some time talking to her about details of a solo exhibition they were planning. When he finished, he put the device back on the table.

Lalo caught her gawping at him and at the small black phone. He smiled, and shrugged. ‘I know, people don’t use phones like that anymore.’

‘I actually haven’t seen one like that in a while.’

‘I know,’ he laughed. ‘I was using an android before. But then one day it struck me that we spend so much time seeing the world through this small device in our hands that we don’t really experience the world around us.’

‘Hmm,’ she said. ‘So how do you connect with the world then?’

‘I am not a caveman,’ he said. ‘I have a laptop and an email address. I just don’t want to spend every five minutes looking at a phone in my hand. There is so much more to see, so many beautiful things and ugly ones too. The little details of life. So easy to miss if you are always looking at your phone.’

She nodded and sighed. ‘I’m afraid I am addicted to Instagram and TikTok. I mean, it’s good for business and all. And for fun. it’s so hard to not be on your phone,’ she said, putting hers in her handbag. She glanced around the studio and her attention was drawn to the paintings. Setting her bag down, she got up to look at them. A portrait of a little girl with a ponytail, a racehorse charging through a dust haze, a woman whose fragmented face was a collage of colourful cubes, bright and sober.

Out of the corner of his eyes, Lalo observed her nodding at the paintings, her eyes gleaming. She reached to touch one, lightly running her fingers over the colours, the texture.

He shook his head. What sort of person does not know not to touch art?

As she came upon his latest, he was mildly satisfied to see her recoil, head jerking back. After a moment, she leaned back in, studied the painting and then turned to him.

‘This is you?’

‘Yes.’

She shook her head. ‘That is … interesting.’

He folded his arms across his chest then unfolded them and reached for his beard. He was intrigued by her word choice and chuckled at how affected he felt by it. Interesting: A word hovering between good and abysmal. Which way the word tips, often had nothing to do with the work itself. In the weeks since he started creating these works, it would be the first time he would pause to consider them, try to wrap words around them, words that would qualify them as works of art, not as fragments of his lives, or rather the ends of his past lives as he had always perceived them.

‘Well, I’m not the first artist to feature in his own works,’ he said. He was not the first to paint his own end either. He wondered if she knew of Caravaggio, had ever seen any of his paintings and witnessed his morbid obsession with beheadings. She hadn’t.

‘These are … gripping, in a powerful, disturbing way,’ she said.

Lalo frowned. Perhaps melancholic, and dark. Disturbing, yes. But gripping? In any case, these were not thoughts that occurred to him while painting. He had only focused on the images in his head and how they made him feel. Children of the haze, he called them sometimes. Born from the feverish mist he had envisaged them in, in which he had awoken at precisely 2:14 every night since the train, stilling his trembling hands as he stroked the canvas with his paint-daubed fingers. Every dot, every line, every stroke inscribed with memories of dying, as if he were living the moment again. He would finish in delirium, fall onto the sofa and relive the events that led to the moment captured on his canvas. As much of it as he could remember.

That first night, after the fever, he had recovered to a noise he did not at first recognise and two yellow beady eyes in a chalk-white face peering into his. He had wanted to scream until he realised it was only his parrot, Diallo. Its high-pitched squawks had stirred him, and he found that he had slept, or passed out—he could not be sure which—on his sofa in his own living room. Lalo had crawled off the sofa and opened the windows, flooding the room with light and letting out the miasma of his sudden affliction. Just as he turned back to the room, he found himself accosted by a painting he did not at first remember creating. He jumped back, knocking over a glass he had left on the floor, the water spilling across the rug, the spread evoking a snapshot, a memory of his blood pooling around his head, seeping into the black earth on which he lay. He skipped over the water, and the glass, and sat on the sofa, contemplating the work as if someone other than himself had stolen in during the night and created it. Even as his hands were caked with the pastel he had hand-painted the background with.

On the canvas before him was the moment just before he was bludgeoned, his back pressed into the train seat, arms raised to protect his head from the swinging club, the blur of it whooshing towards him depicted by the black paint. What struck him even then was not just the style, the deep earthy colours—like the sands he had been buried in—unlike the brazen colours of his previous works, but also the vividness of the fear and shock in his eyes, and in the lines on his face, as if he himself had modelled for the painting.

‘There is something about the expression,’ she said. ‘I don’t know how you captured it. Did you, I don’t know, sort of photograph it or maybe perform it in a mirror before …’

Lalo lowered his head. ‘It is not a performance.’

He walked to the painting and moved it an inch to the left, then to the right. He looked up and found her staring at him, as if she could see a scar where the club had struck him. Straightening, he brushed his hand over his temple and pulled down his shirt.

‘You are grumpy.’ She moved away from him and the paintings. Standing by the window, she looked out into the greyness outside and sighed. Curtains of rain fell, their hem teasing the panes.

Again, her bluntness drew a smile to his face. ‘I am sorry,’ he said. ‘I am just a bit … angsty about this series,’ he paused, weighing the words. ‘You see, I am going through a … phase. I am experiencing something, you know. My brother thinks I am mad.’ He pointed at his head, widened his eyes, stuck out his tongue and shook his head about in a way that made her laugh. ‘But I am not, you see.’ He paused and looked around, smiling. He liked the way her smile lingered, like an afterglow on embers. ‘I can show you the rest, if you like.’ He felt silly standing there, hands folded in front of him, a grimace on his face. Since he had never shown anyone before, or even thought of showing anyone, he was unsure what her reaction would be.

She smiled, shrugged and walked towards him. ‘Well, it’s raining anyway.’

‘Yi hakuri. I am mostly called Lalo. Yarima Lalo,’ he said, his tone laced with apology and then a hint of mischief. ‘I am the painter, as you can tell. I am sure you have a name, except you don’t mind being called the 2:14 woman.’

She laughed. ‘Aziza.’

‘Aziza,’ he echoed, bowing slightly with mock flourish. ‘Again, I apologise for my … attitude. I am not fully sure what I am experiencing, you see.’

‘It’s okay, I guess.’

In five of the six paintings, she found his face projecting the horror, fear and certainty of dying, and the moment just after.

‘These three,’ she began with a sweeping gesture that took them in, ‘they seem connected. By the train.’ There was the first one she had seen, with his arms over his head, protecting it. Tucked behind it was another with his head bashed in, blood spurting, his body slumped against the train seat, only part of his face visible.

‘They are.’

There was another of him in a cornfield again cowering from an impending blow. In the next one, there was only a bloody rock lying amongst the corn. Black soil. Green corn. Red, red blood. In the final painting, another blow approaching, the rims of his eyes, bleary, weary the blows; of living, of dying, of the inevitability of it all. He seemed smaller in that one, shrunken even.

‘What are they about?’

‘A man being killed, obviously.’

‘And the man is you?’

He nodded.

‘In all of them?’

‘Well, in the last one, of a man about to be killed. That hasn’t happened yet … I think.’

She turned to the painting of him spotlighted against a grim background, cowering. ‘Wait, ban gane ba. You mean these ones have happened, like for real?’

He turned away, mumbling about other unrelated paintings—outside, the rain was subsiding, the garbage it had swept out littered the street.

‘I’m sorry, did you mean these have happened?’

He sighed. ‘It’s hard to explain, you see.’ He scratched his beard and grimaced. ‘It does not make sense at all, I know.’

‘Why don’t you explain them to me, please? Dan Allah.’

During the long silence that followed, he wondered if he should mention the irrationality of his preoccupations since that train freighted to him memories from a previous life. Wondered if she, this stranger, would laugh at him. She struck him as a romantic—with the nose stud, her eagerness for life and friendships and affinity for Instagram and TikTok. He suspected she would be biased towards the beautiful and unattainable, perhaps paintings of flowers, moonlit lovers in idyllic postures and the such, not the grim realism of these paintings. He felt an endearment for this disposition. For her. For the way she leaned towards the painting, scowling at them in concentration, mumbling to herself.

Outside, thunder growled like a hungry beast. Ambling to the window, he watched sheets of water sliding off the pane. The street had been surrendered to the rain, a few parked cars and the toppled plastic table of the phone card vendor, a token of vanquished human presence. How it had escaped being blown away by the wind intrigued him for a brief moment.

‘These deaths you paint, were they things you witnessed?’ Between them, there was his table, which she had walked around, and the small expanse of the studio. She fiddled her fingers.

‘I suppose you could say that, yes. I … experienced them.’ He turned and caught her jaw hanging. At that point, she did not look as young and gullible as he had initially assumed. In the smooth lines of her jaws, in the way they grew taut, in the way her eyes narrowed, her misgivings about his state of mind manifested. And when she gripped the edge of the table, as if it were something she could use to shield herself from him, from his delusions, or the threat of his brazen insanity if it were to flare, her thoughts were undeniable.

For a moment, they studied each other. She a sceptical inquisitor, he a child caught telling a lie.

Except he wasn’t.

‘Toh fa! Babban magana,’ she exclaimed at last, gaze darting around the studio, resting briefly on solid things within reach—a foot long bronze statuette of a Fulani milkmaid resting on a pedestal to her left, a faceless burnt wood figurine on her right, one half darker than the other.

‘And you died in these … episodes?’

‘Look, I’m sorry.’ He hurried over to stack the paintings and lean them against the wall. ‘Like I said, this is not easy to explain. I am sure you think I am bullshitting you.’

Aziza nodded, eyes still darting. ‘They are beautiful. Beautifully realised, I mean. I suppose they will fetch quite a lot of money.’

‘They are not for sale.’

‘Oh.’

‘This is not art,’ he said and then turned to her with a helpless gesture. ‘I mean, this is life, do you understand? Life. And death.’ The last bit came out like a wisp of smoke escaping a blown-out candle.

She nodded and after an appropriate interval, she stepped back and feigned interest in his other paintings. He was right. She dawdled over a cubist painting of a nude woman reading.

Lalo idled, wondering if he should say anything else or just let the assumption of a lie be washed away in the rain. He did not want to apologise anymore, but for some reason, he did not want her leaving with questions about his sanity.

‘The paintings, they will probably be in an exhibition, I think.’ That was also the first time the thought had occurred to him. ‘But they will not be for sale. Not these ones, at least.’

‘I see.’ She grimaced. ‘Well, thank you for showing me your works. The rain seems to have stopped. I must get home to my daughter.’

‘A daughter? How old?’

‘Five.’

He nodded. ‘Allah ya raya.’ He wanted to add that he was sure she was as beautiful as her mother was but he let the words bubble around in his mind instead.

‘Ameen. Thank you. And thank you for letting me stay. I could have been a serial killer, or a thief.’ She chuckled.

He smiled. ‘Or just a muse.’

She smiled again and adjusted her veil over her bosom. At the door, she turned back to him with a finger held up as if she were a pupil asking permission in class. ‘I’m sorry, if you don’t mind me asking, about your paintings, who was doing the killing in them?’

‘A scorned rival in love. Or a husband in one case.’

Aziza nodded, her gaze travelling the country between his head, down his black T-shirt and red pants all the way to his shoes, in this journey leaving footprints of her doubts—about his story, about his sanity. ‘Well, nagode. Sai anjima.’

‘A pleasure,’ he said. ‘Sai anjima.’

‘Nice touch putting the child in, by the way,’ she said.

‘What child?’

‘The one with the cart. In all the paintings. Top right corner. First thing I noticed,’ she said.

Lalo turned to his paintings and sure enough in the top right corner of every one, there was the form of a child with a cart. Sometimes a shadow or a cloud; a silhouette—sometimes a gap in the foliage that always formed the same shape, like some secret motif he had been tucking into his art. Except he was just observing them for the first time. He leaned in closer to inspect the form.

Until he heard the little silver bells on his door tolling, announcing the departure of the woman who had arrived at 2:14, wrapped in a leaf storm.

~~~

- Abubakar Adam Ibrahim is an award-winning Nigerian writer and journalist. His debut novel, Season of Crimson Blossoms, won the 2016 Nigeria Prize for Literature and the 2018 Prix Femina. His short story collection, The Whispering Trees (2012), was longlisted for the Etisalat Prize for Literature; its title story was shortlisted for the 2013 Caine Prize for African Writing. He is a Gabriel Garcia Marquez Fellow (2013), a Civitella Ranieri Fellow (2015) and was included in the Hay Festival’s Africa39 anthology of the most promising sub-Saharan African writers under the age of 40. His non-fiction work has appeared in publications including Granta and Berliner Zeitung.

~~~

Publisher information

When brooding artist, Yarima Lalo, encounters a moving train for the first time, two serendipitous events occur. First, it triggers memories of past lives in which he was twice murdered—once on a train. He also meets Aziza, a woman with a complicated past of her own, who becomes key to helping him understand what he is experiencing. With a third death in his current life imminent, together they go hunting for remnants of his past lives. Will they find evidence that he is losing his mind or the people who once loved or loathed him?

‘A gripping, layered, passionate and haunting novel with tones of otherworldliness. Abubakar’s prose sparkles with poetry, wisdom and compassion. This is a complex and unforgettable story that will keep you up at night.’—Bisi Adjapon