The JRB Patron Ivan Vladislavić chats to Editor Jennifer Malec about memory, nostalgia and his latest novel, The Distance.

Ivan Vladislavić

Ivan Vladislavić

The Distance

Umuzi, 2019

Read an excerpt from The Distance here

Jennifer Malec for The JRB: You are often referred to as a ‘Johannesburg writer’, and I don’t think you’d dispute that marker, but in fact you were born and raised in Pretoria. As far as I can tell, The Distance is the first of your books to be set largely in that city. How was the experience of writing about your hometown for the first time?

Ivan Vladislavić: In some ways I found it easier than writing about Johannesburg, especially because I was dealing with the past. Over the years, I’ve spent less and less time in Pretoria and new experience hasn’t been layered over the old. Parts of the city, like the area around the station and the old Berea Park sports club, are preserved in my memory like museum exhibits, although they’ve changed enormously in reality.

There’s more of Pretoria in my work than one might think. My early stories are full of its styles and atmospheres. This is true even of the more fantastical settings which obscure their building materials. There’s a single hint in The Folly that the suburb where it’s set is in Johannesburg, but everything else suggests Pretoria.

The JRB: Do you plan to return to Pretoria in future books, perhaps to central Pretoria, where you spent your early years? For someone who values walking, I imagine the city centre of Pretoria offers quite a different experience to Johannesburg.

Ivan Vladislavić: I have been back in a story called ‘Save the Pedestals’, most of which plays out in an inner city that resembles Pretoria, including an out-of-kilter version of Church Square. There’s an opera house on the fictional square, for instance, and it’s a long time since this was true of the real city. Writing the piece allowed me to retrace some of my old paths, but only in memory. I couldn’t go back until I’d finished The Distance.

The last time I walked around that area it was looking shabby. It really irked me that the Capital Theatre, one of the grander of the old movie palaces, had been gutted and turned into a parking garage. Of course, the sense of losing parts of oneself as the skyline changes is very common in cities. This is Colson Whitehead in The Colossus of New York: ‘Maybe we become New Yorkers the day we realise that New York will go on without us. To put off the inevitable, we try to fix the city in place, remember it as it was, doing to the city what we would never allow to be done to ourselves.’

The JRB: In a conversation with SJ Naudé in Granta, you discussed the way Marlene van Niekerk and Ingrid Winterbach’s novels almost act as archives for the Afrikaans language, by including obscure words and expressions, or referencing little known songs and poems. In a way, your books do something similar, The Distance in particular. One of the reasons I can’t wait to lend the book to my mother is that I know she’ll delight, as I did, in seeing certain colloquial phrases in print: ‘she had a cadenza’, ‘don’t give me a thousand words’, ‘he was all Harry Casual’, ‘they got so het up’, and so on. Do you see yourself as an archivist of language?

Ivan Vladislavić: I hadn’t thought of myself in these terms exactly, but they seem apt. One of the pleasures of reading, especially if you have a taste for the writing of the past, is that books preserve words and phrases, and phrasings and syntaxes, that have fallen out of use. It’s one of the reasons I enjoy Stevenson or Twain, for instance. In my own writing, words and idioms are used as markers of the past, but they also give me pleasure in themselves, just for their strangeness or novelty. It’s the same bird-watching instinct that draws me to dictionaries. A few days ago, I heard a man on television say of an acquaintance that he’d ‘gone for a Burton’, and it was like hearing a joke that used to tickle me when I was a child. My parents and older relatives were treasuries of expressions like this. My grandmother used to call me ‘young fellow m’lad’ when I misbehaved, with no sense that her Victorian idiom only made things worse.

The JRB: A character called Branko appears in Portrait with Keys, and there are similarities between that Branko and the one who crops up in The Distance. Portrait with Keys is often taken as non-fiction, and I’ve seen, in reviews and so on, the two brothers in the book referred to as Ivan and Branko, with the inference being that they are real people. I’m not sure whether you really do have a brother called Branko, but I was wondering why you decided to return to the character in The Distance?

Ivan Vladislavić: Branko arose as a composite figure when I was writing Portrait with Keys: I needed a character to act as a catch-all for attitudes and opinions I didn’t want to attach to anyone else. As writers do, I concerned myself with solving a problem in the text and Branko was an efficient mechanism for doing this. It was only after the book had been published, and people began to refer to him or ask after him, that he materialised fully for me as a character, like all the others, with an imagined real-life counterpart. I was often asked: What does your brother think of the book? Sometimes I could answer quite honestly: I don’t know.

It’s easy to miss the unthinking way in which composition proceeds, especially for younger writers with reckless imaginations (a good thing, and we have Toni Morrison’s word on it). A while ago I watched a television interview with Clarice Lispector, apparently the only one she ever gave, in which an interviewer with a rather cold-blooded, lawyerly style tried to pin her down about her influences and education. Looking utterly pained, smoking intensely and playing with her cigarette packet, she valiantly evaded him: ‘I really don’t know, because I mixed everything up. I read novels for young girls and mixed it up with Dostoyevsky. I chose books by their titles and not by their authors because I didn’t know anything. I mixed it all up …’

Anyway, I realised soon after Branko went out in public that I wasn’t done with him. Or he wasn’t done with me. I remember telling my German translator Thomas Brückner that I might ask Branko to write my biography. This isn’t quite what he does in The Distance, but there’s clearly a link. His presence in the novel should signal that he’s a fiction, although the fact that some passages read like memoir might obscure this. I turned to him, initially at least, for the same qualities he showed in the earlier book: to complement or contest the views and position of the main character.

The JRB: In the conversation with Naudé that I mentioned, you said that you ‘cannot imagine writing a book with someone else’, but that ‘the bonded autonomy of a joint project does appeal to me’. In a way, The Distance is ‘written’ by its two protagonists, the brothers Joe and Branko. You have collaborated with visual artists before. Was this a kind of foray for you into collaborative writing?

Ivan Vladislavić: This is an intriguing question. I’ve often made a distinction between a collaboration, where the parties work on the same product; and a joint project, where they work alongside one another, responding to the other party’s work but responsible only for their own. I was encouraged to draw these lines by Joachim Schönfeldt, one of the artists I’ve worked with.

When I was writing Portrait with Keys, I had the idea of inviting various people to contribute stories to my book with the aim of ‘creating a sympathetic or argumentative chorus’. If the scheme had worked, these texts, interleaved with my own to create a strand called ‘The Visitors’ Book’, might have been seen as a many-headed ‘joint project’. In the event, it was ill-conceived and fell through, and I had the uncomfortable task of sending the visitors away.

Joe invites Branko into The Distance in much the same spirit. At the outset, he creates a rigid division between their contributions. You could say he presents it to his brother as a ‘joint project’: I’ll do the stuff on Muhammad Ali, he tells him, and you can handle the childhood memories. Branko is rightly suspicious of Joe’s motives. He sends the whole idea up in his comments about his brother ‘making space’ for him in the book. As it turns out, a fictional character may be no easier to uninvite than a real person. Having read the book, you know that Joe finally gets the short end of the pencil. The house guest takes over, as they sometimes do.

Stepping back for a moment, I would say that both Joe and Branko are fictional characters and my job as the writer was to move them around and get them to interact, as usual. But the novel gives voice to both characters and dramatises a struggle between them for control over the story, and my allegiances had to shift between the two sides. I sometimes felt that I was collaborating with one or other of the brothers, or, more disturbingly, with one or other idea of myself.

The JRB: Joe, the writer, the one good at ‘making things up’, is working on a book about his childhood, and approaches the more pragmatic Branko for help ‘remembering things as they actually were’. The novel itself is full of remarkable detail: the interiors of nineteen-seventies suburban Pretoria houses, the look and feel of school classrooms at that time, the games, the photocomics, the bioscopes. How did you aid your memory while writing the book? Did you keep diaries, or have discussions with family members, or are you just very good at remembering?

Ivan Vladislavić: The most direct prompt for memory was a collection of news cuttings from those years about Ali’s career. Among them are some full pages, and even entire sections from the newspapers, and they include news reports, photographs from social events, adverts and so on. The social historian Tim Couzens always argued for the value of the physical archive as a kind of time capsule. Besides the story you’re following as an historian or biographer, an archive containing documents like newspapers and letters preserves an entire world of contextual detail. Apart from reading the cuttings, and some of the other texts referred to in the novel, I decided not to do any other research. I have a fairly good memory and I tend to dwell on the past. Your memory gets sharper if you exercise it.

The JRB: In his book White Scars, Denis Hirson speaks about remembering—‘digging up’—an everyday object or experience that you hadn’t thought of for years, and how because it is not a memory that has been ‘blunted, shaped and reshaped’ in an anecdote, it tends to be ‘strangely, disproportionately alive’. Was this vitality something you aware of tapping into as you were writing The Distance?

Ivan Vladislavić: Hirson’s memory books, especially I Remember King Kong (The Boxer), recover the past in a very concentrated way. If you grew up in the same years as Hirson, more or less, as I did, reading the books is an intense, even uncomfortably intense experience, something like eating a whole box of chocolates. My editor was reminded of Hirson when we were working on The Distance and I see why.

Although I didn’t go about it consciously, during the writing I certainly uncovered things I hadn’t thought about for decades, and they do have an unusual power. Hirson writes that the ‘I remember …’ mechanism had a momentum of its own, that the more he dug, the more he turned up, and that’s also a familiar experience.

White Scars is a marvellous book, full of insights into reading and writing. He came up with a really unusual form: it’s a memoir built on a close reading of books that were important to him, complete with an apparatus of notes and glossaries. I don’t think I’ve come across quite this amalgam of critical reading and life story. There may be a parallel with the use of the news cuttings in The Distance, although Hirson is preoccupied with some fine writers—Breytenbach, Carver, Perec—whereas my crew, the scribes of the fistic kingdom, will generally be regarded as hacks.

The JRB: This is a long one. I hope it makes sense. I was chatting to a mutual friend of ours, Dave Southwood, recently, and he mentioned the parallels he’d noticed between The Distance and Jacob Dlamini’s Native Nostalgia. Dlamini’s memoir opens with a description of his whole street in Katlehong listening to their radios and cheering as Gerrie Coetzee beat American boxer Michael Dokes to win the world heavyweight title in 1983. For Dlamini, the ‘wireless’ was an important imaginative space that gave black South Africans a freedom of movement they didn’t have in reality, and it becomes a site of nostalgia, albeit a complicated one. In a way, Joe’s infatuation with Muhammad Ali seems to originate in a similar place—although interestingly he cannot recall if he ever heard Ali on the radio. As a child, Joe knows Ali only through writing, and that writing gives him access to, or even a kind of ownership of, a different imaginative space. But as an adult, when he is trying to write a book on Ali, this site of nostalgia causes Joe great frustration. I’m interested: have you read Native Nostalgia? Were any of these ideas running through your mind when you wrote The Distance?

Ivan Vladislavić: I read Native Nostalgia when it was published (2009) and enjoyed it very much. It was a bold response to a range of ideas then running through our culture: the turn towards city writing; ideas about nostalgia in the work of theorists like Svetlana Boym; the persistent echoes of earlier calls, by thinkers like Ndebele and Sachs, for new approaches to writing or making art after apartheid. Dlamini brought these currents together brilliantly. Formally the book is conventional—Hirson’s White Scars, published a few years later, is a far more adventurous formal experiment—but I admire it enormously. I see the point of a comparison with The Distance. Both books deal with memories of childhood and how to understand them in the context of a divided history. On the other hand, while I appreciate the restorative impulse that drives Dlamini’s book, I am wary of nostalgia myself. I was once interested in the notion of a ‘critical nostalgia’, but I’m no longer sure what that means. I hear Zoë Wicomb’s sceptical commentary on how easily nostalgia fades into ‘plain old fond remembrance’.

Radio is very important to people of my pre-television generation. There’s a lot about listening to the radio in Hirson’s I Remember King Kong, and the schedules of radio programmes I came across in the news cuttings are unusually evocative. Before the visual media reached into every area of our lives, there was something especially intimate about listening to the radio in your own home.

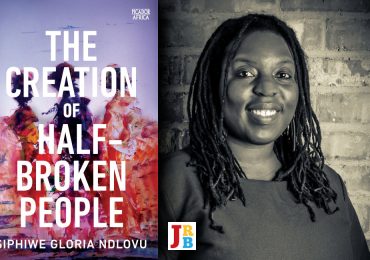

The JRB: What is also interesting is that for Dlamini and his family it didn’t matter that Coetzee was a white Afrikaner fighting a black American; they chose the Boksburg Bomber and made him their own. I interviewed the author Siphiwe Gloria Ndlovu recently about her book The Theory of Flight, which is set in an unnamed southern African country, and asked her about its references to music by The Carpenters and Dolly Parton. She said that for her Dolly Parton was not a global cultural reference, but very particularly a Zimbabwean cultural reference, because of how popular she was in that country. Do you feel similarly, at all, about the figure of Muhammad Ali in South Africa?

Ivan Vladislavić: This makes sense: culture from other places is refracted through the local and becomes something different. One can see it clearly in the music world. Pop singers and movie stars became international if not global figures before athletes and sports teams. My novel deals with the era in which new satellite broadcasting technologies began to turn sportsmen (and the focus was definitely on men) into entertainers and then into global icons.

People must have found it challenging, though, making Ali their own in very different political situations. He unsettled ideas about race, but his provocations were not straightforward. For instance, he would position himself as the black people’s champion even when he was fighting black boxers, from Floyd Patterson to George Foreman, and he liked to rile his opponents by calling them sellouts and Uncle Toms. Before the Rumble in the Jungle, he said that when they got to Africa, ‘George Foreman’s going to be the White Man and I’m going to be the Black Man.’ It’s fascinating to imagine what people made of this in the South Africa of the seventies.

The JRB: Joe’s archive, as Branko discovers, is supplemented by the snatches of news stories that appear on the reverse of the cuttings, which you have inserted as prologues to each chapter. These brief textual images add so much to the book’s atmosphere, and I was wondering if you could talk a little about why or when you decided to include them.

Ivan Vladislavić: As soon as I started to work with the cuttings, I was intrigued by the information on the reverse side. Something was always catching my eye. What appears there is totally random, which may be part of its appeal: often the detail is of the kind you would look past if you were paging through a newspaper, but as an isolated fragment it seems full of meaning. I hoped that the bits and pieces presented as ‘epigraphs’ to the chapters would be magnified in a similar way. The idea of using the ‘reverse world’ in the novel itself came quite late. Among other things, it was an unobtrusive way of creating a sketchy timeline to help the reader navigate the chapters.

The cuttings aren’t marked to show which newspapers they were taken from. When the book was finished, and I was trying to identify the sources of the quotations systematically, the reverse side of the cuttings came in very useful. Often I could figure out which newspaper I was dealing with by the typography or the formatting of datelines and so on. Regular features like radio schedules or cartoon strips also helped to identify sources. For instance, Modesty Blaise was in the Pretoria News and Calamity Gulch in the Sunday Times.

The JRB: The cover of The Distance is reminiscent of a passage from Portrait with Keys, in which the narrator is trying to picture a man he saw ‘two or three times’ outside his house. He has already written about this man, however, and he says: ‘Every time the memory man tries to come from the shadows, this written man, this invention you’ve already met, steps in front of him.’ Later on he adds: ‘There is something to be said for falling back on the fallible memory, the way one falls back on a soft bed at the end of a working day.’ Flash forward to The Distance, and it seems to me that this is Joe’s central difficulty: he is unwilling to fall back on this soft bed. His notes and annotations become, he says, ‘a shadow of obscure intent over the blank page on which a book might actually start.’ When Branko is trying to finish the book he says: ‘I can’t see the past any more. It’s a dark, bewildering place.’ Does the shadowy nature of memory interest you? How do you battle this darkness in your own work—or do you embrace it?

Ivan Vladislavić: The fallible memory is surely at the heart of writing fiction. I like to quote Graham Greene on the subject: he said something to the effect that forgetting is essential to writing fiction. Everything you forget is the ‘compost of the imagination’. Without the freedom that a faulty, inventive memory brings, novelists would all be social historians. It’s interesting that Joe, who can’t seem to get past the facts of the archive, doesn’t grant this freedom to Branko: as you noted, he wants him to remember things ‘as they actually were’. He wants him to be an historian too. But it appears that Branko cannot follow this advice.

I used to make grand claims for the imagination, but now that every crooked politician comes armed with their own facts, I can’t stop thinking about fidelity to the truth. Of course, the struggle of memory against forgetting (to resuscitate Kundera’s maxim for a moment) is not a simple struggle of the factual against the imagined, of ‘what actually happened’ against ‘what you just made up’. Narrative truth, the truth arrived at in fiction or through storytelling, is a complex notion, and needs to be defended sensibly in a time when ‘narrative’ has become a buzzword and ‘That’s just your narrative’ is the quickest way to shut down debate.

I’d forgotten the passage you quote from Portrait with Keys where the ‘written man’ obscures the remembered one. There’s a similar idea in Double Negative: that photographs sometimes annihilate memory. The writer accustomed to recasting personal experience as fiction might well find a wall of inventions rising up between him and the past. Once something has been shaped in language, it starts to feel ‘right’ and it becomes harder to see it another way. Writing reveals and conceals the past at the same time.

I’m not sure what to make of the persistence of this imagery, but there’s a ‘memory man’ in my first book. In the story ‘A Science of Fragments’, he’s described as ‘the other man, the dark one, cut off by the edge of the photograph, in shadow …’

The JRB: In the present day, Joe is determined to rely on the incomplete, erratic and crumbling ‘archive’ of newspaper cuttings he collected in scrapbooks as a child to construct his story. On the other hand, Branko wants to see Ali’s fights for himself, and ends up going down a YouTube rabbit hole for several days: ‘I spiral out into the superabundance.’ I was wondering if this reflects on your own writing practice. Are you, for example, someone who disconnects the internet while you write? Or do you whirl happily in the superabundance?

Ivan Vladislavić: The internet is a deeply disillusioning medium and I avoid it when I’m writing. Nearly all the research I do is retrospective, just to confirm or detail something I’ve imagined, and then it’s useful to have a lot of information at your fingertips. But most of the time I find the excess appealing only as a distraction.

The JRB: The short story you mention above, ‘Save the Pedestals’, has been adapted for the stage, and made its debut at the Puppentheater Halle in Germany last year, before a run at the Baxter Theatre in Cape Town in March. Could you tell us a little about how this collaboration came about, and whether there are any plans to bring the production to Joburg?

Ivan Vladislavić: Around the beginning of 2017, the South African director and choreographer Robyn Orlin, who lives in Berlin, was commissioned to develop a production with the Puppentheater Halle and the Handspring Puppet Company. She approached me to say she was interested in adapting one of my texts. I offered her ‘Save the Pedestals’, which was unpublished and felt like it lent itself to a theatrical treatment. I met the company when the workshop process started and we spoke about the story, but I wasn’t involved in the adaptation. The production will travel to Paris in the next few weeks, but there are no plans to bring it to Joburg. The story will be published early next year.

The JRB: I’ve read that it was your idea to use a different typeface for the newspaper quotations in the book. Is it unusual for an author to be involved in a book’s typesetting or design? Did you receive any resistance from your editors or publisher on this?

Ivan Vladislavić: On the drafts I started out using italics for the quotes, but I found it tiresome and switched to contrasting typefaces. I wanted a more subtle version of this in the book. My publisher Fourie Botha was happy for me to get involved and I worked closely with Umuzi’s designer Fahiema Hallam. We tried many different options, including a smaller point size in the same typeface, before settling on a solution. I think this level of involvement in the design is unusual with a trade paperback. Smaller presses doing specialised kinds of books often work more closely with their authors. Some trade publishers have run page designs past me, and I suppose my experience as an editor might have encouraged them to do so, but more often I’m not involved at all. I think most writers are happy to leave these decisions to the publisher.

The JRB: You worked for many years as an editor, so I’d like to ask you a question related to that. In an interview in our last issue, Michael Barron, an editor from Melville House in the United States, said that he is very interested in emergent South African writers, but that he often wishes the books had been ‘given a much more rigorous edit’. What would your opinion be on that?

Ivan Vladislavić: I agree. I’m not sure what the problem is, but it’s been a matter of public discussion, sometimes heated discussion, for at least ten years. Just last week, the judges of the Barry Ronge Fiction Prize mentioned badly edited books when they announced the longlist for this year’s prize. Editors need time to make a difference, and that costs money, which publishers are often short of. Writers also have to trust editors and take their advice, in the interests of arriving together at a better version of the book. I get the feeling that strong editing is not always welcomed or appreciated. Also, skilled editors can and do make an enormous difference, but they’re not magicians, and what matters most is the quality of the unedited manuscript to begin with.

The JRB: Finally, we’re always on the lookout for new (to us) or interesting authors, so we like to conclude by asking: do you have any book recommendations to make based on your recent reading?

Ivan Vladislavić: Gerald Murnane, Tamarisk Row (Giramondo); Tomas Espedal, Tramp (Seagull); Ulrich Raulff, Farewell to the Horse (Penguin); Joseph Mitchell, Up in the Old Hotel (Vintage).