The JRB Contributing Editor Panashe Chigumadzi presents a new reading of the work, career and life of Dorothy Masuka, arguing that Masuka transcended simple categorisation and presented a revolutionary challenge to white supremacy and structural patriarchy alike.

1. We are not the first

We sometimes forget that we are not the first to be transgressive. Ya. We, who write of Pan-Africanism and feminism and womanism and and and and, sometimes forget that our mothers and grandmothers and great-grandmothers have been where we are. Sometimes, it’s not so much that we forget that we are not the first, it’s that we don’t know.

If we listen a little more closely, or ask questions of our mothers and grandmothers and great-grandmothers, we might be let in on grand tales of their transgressive and troublesome ways. Maybe our mothers have grown quiet, tired of deaf ears. Maybe our mothers are no longer here with us for them to tell us their tales themselves. And now, because we were arrogant or ignorant or both, we are left to ask, where do we go in search of our foremothers’ stories? Who will tell us of their troublesome and transgressive lives?

*

If we were to listen to ‘Aya Mahobo’ we would know of women who gleefully pointed at their generous breasts and buttocks as they danced and taunted men at open air parties. If we were to listen to ‘Nolishwa’ we would know of a beautiful girl who wore trousers and was seen alone with men. If we were to listen to ‘Pata Pata’ we would know of the commotion that stylish ‘good-time girls’ stirred up as they swayed along the township pavements enticing men to touch them. If we were to listen to ‘Khauleza’ we would know of ‘Shebeen Queens’ and backyard brewers of Skokiaan who urged each other to hurry up and away from the baton, only to come back and defy it again. If we were to listen to ‘Wathint’ abafazi, Strijdom’ we would know of women who marched against the searching of their bodies, the breaking of their homes and the undermining of their freedom of movement by the dompas. If we were to listen to ‘Lumumba’ we would know of women who dreamed of a new dawn for all of Africa and her children.

*

Where do we go in search of our mothers’ stories?

How will we get to know we weren’t the first to be here?

Who will tell us of their troublesome and transgressive lives?

None other than themselves.

Listen.

2. Chimanjemanje, chinyakare

In the post-war period of the early nineteen-twenties thousands of Southern African migrant workers moved between the colonial industrial centres. As a young Zambian chef served white passengers on the region’s trains, important consolidations were being made in the politics and borders of the region. In 1923, Cecil John Rhodes’s British South Africa Company (BSAC), which had annexed Southern Rhodesia in 1890, handed over administration to the government of an internally self-governing colony, after a referendum on the issue in 1922. 8,774 settlers voted for a colony, while 5,989 supported the position, favoured by former Under-Secretary of State for the Colonial Office Winston Churchill and Prime Minister of the Union of South Africa Jan Smuts, for joining the Union.

In the early nineteen-thirties the railway chef, a young man of the Lozi people, met his future wife, a Zulu woman tending the children of her white South African employers, on a train to Bulawayo. They married in South Africa before his work took them back to Bulawayo, then the railway centre and industrial capital of colonial Zimbabwe, built on the ashes of the seat of the Ndebele kingdom. The couple would have seven children, one of them a precocious Dorothy Masuka. She spent her formative years in colonial Zimbabwe, going to school in Bulawayo before moving to Salisbury (now Harare), and then to a Catholic school in Johannesburg.

With the end of World War II and the election of the National Party in South Africa, Southern Rhodesia’s white settlers enjoyed a new period of prosperity, while the economic position of Africans was seriously undermined by the deprivation of land, the primary means of production in an economy based on agriculture and mineral extraction. A manufacturing boom in the nineteen-thirties, -forties and -fifties meant that the settler economy became increasingly dependent on the urbanised black workers or, in settler parlance, ‘detribalised natives’. The urbanised black workers soon began staging industrial action, culminating in the 1945 Railway Workers’ Strike and the 1948 General Strike.

The increasing numbers of ‘detribalised natives’ posed some problems, perceived not just by anti-colonial nationalists but by Southern Africa’s settler administrators, who believed that their colonies should be ‘white men’s countries’. Crucially, there was a gendered aspect to the settler colonial mapping of time and space, as evidenced by Smuts’s declaration in ‘Native Policy in Africa’, part of his 1929 Rhodes Memorial Lectures at Oxford, that:

It is not white employment of native males that works the mischief, but the abandonment of the native tribal home by the women and children.

Where settler authorities depicted the ‘white man’s town’ as a ‘morally corrupting’ place for ‘tribal natives’, African women in particular were viewed, as Lawrence Vambe describes in his 2007 text ‘“Aya Mahobo”: Migrant labour and the cultural semiotics of Harare (Mbare) African township, 1930–1970’, as ‘inherently debased, temptresses and a hindrance to African progress because they purportedly held onto African cultural traditions described by settlers as obscurantist’. Successive laws, policies and repressive measures were to curb the mobility of what a Native Commissioner of Salisbury in 1928 called ‘the travelling native prostitute’—a term that would continue to be used by settlers and African patriarchs alike to refer to African women independent of male control.

Many African patriarchs did not challenge the settler-colonial creation of the rural-urban, traditional-modern, woman-man dichotomy, fitting so well as it did with the long-held notions underscored in the Shona proverb ‘musha mukadzi’, literally meaning ‘the home is the woman’. Often there was collusion between the colonial state and patriarchal nationalists as to the place and mobility of African women. As industrialising colonial societies drew African men into the modern wage economy of the mines and urban centres, they by implication drew African men into ‘modernity’ or ‘the future’, colloquially understood as chimanjemanje (literally: ‘things of the now’). This was while leaving behind African women, who formed the bulk of rural peasantry, thereby ‘pushing’ African women into ‘tradition’ or ‘the past’, colloquially understood as chinyakare (literally: ‘things of the past’). Treacherous though the white men’s towns were, men could be trusted to negotiate the risks and rewards of chimanjemanje, whereas women could not. And so through the act of evoking the past and tradition as a means to legitimise and assert nationalist claims, African women have often become important repositories of the ‘stable past’, and thus the burdens of national and racial authenticity begin to fall on them. It is then the figure of the ‘prostitute’ who most powerfully symbolises the ‘modern African woman’ who refuses her place in the race-gendered temporality of colonialism.

In early- to mid-twentieth century Southern Africa, the concern with this ‘prostituting’ ‘modern’ African woman and her corrupting influence on African men was so dominant that it became the subject of prominent South African journalist Rolfes Robert Reginald (RRR) Dhlomo’s An African Tragedy, the first English-language book by a Zulu writer. The 1928 novella foreshadowed the dramatic increase in the interwar period of black urban populations across South Africa, which resulted in the number of Africans in Johannesburg nearly doubling. In Dhlomo’s chronicle, a male migrant labourer, who has left his obedient Christian wife in rural Zululand to seek work in Johannesburg, finds his downfall in the arms of a prostitute, a domineering urban woman figure. Dhlomo was also the assistant editor, to Victor Selope (VS) Thema, at the ‘progressive yet moderate’ newspaper The Bantu World, which had the distinction of being South Africa’s first black daily, and which was also the first to offer ‘women’s pages’. In the interwar period, when most Africans in Johannesburg lived in close proximity to poverty, the class-conscious urbanised black elite were concerned with the promotion of a respectable urban femininity that would distinguish their daughters and wives from the disreputable urban female figures of the prostitute and ‘Shebeen Queens’ that black leaders had long associated with South Africa’s towns and townships. Thema and Dhlomo performed a sort of patriarchal ventriloquism on the ‘women’s pages’ by editing them and deploying mostly male writers for the section. ‘No nation can rise above its womenfolk’ declared ‘The Son of Africa’ (likely Thema), justifying the paper’s new focus in the inaugural women’s pages.

3. ‘The Famous Rhodesian Singing Star’

As strong as the decolonising winds of change that blew across the continent were, they could not shake the iron resolve of Southern Africa’s white settler minority regimes. By the nineteen-fifties, as Dorothy Masuka was coming of age, the establishment of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland—today’s Zimbabwe, Zambia and Malawi—briefly opened a window of hope that conditions would improve for Africans. Instead, the ‘new’ politics of racial ‘partnership’ was envisioned as a ‘horse and rider’, where Africans, predictably, were the mules of the settler state. Instead of easing, life for Africans worsened. Right-wing hardliners came to dominate the Federation Parliament, defeating efforts to end racial discrimination in public places and to reform labour and land laws.

During this time, panic over ‘influx control’ ensured heavy settler state regulation of Africans’ mobility, alongside efforts to ‘retribalise’ them by ‘fencing off’ Africans from European-designated activities and spaces, and creating designated areas and activities for ‘natives’. But far from being the bewildered tribesmen in white men’s towns the colonial authorities saw them as, Africans were staging a complex and often contradictory negotiation of chimanjemanje and chinyakare, the old and new, tradition and modernity, appropriating what worked for them and what didn’t. Africans did more than simply act out a false consciousness, they negotiated with and subverted the colonial state. They continued to engage in illicit economic activities, used colonially designated ‘recreation halls’ for their own political ends, and at a cultural level used dance, song and drama to perform and contest their embattled presence in the urban centres.

At a time when Africans were not allowed to drink distilled alcohol or ‘European beer’ in the African beer-halls, the kokotero, or cocktail bar, was an upscale place where Africans would be served ‘European’ brands such as Castle or Lion Lager.

Only ‘gentlemen’ dressed in suits and ties, and their ladies ‘dressed to kill’ in evening gowns, were allowed into the cocktail bar, the ‘kokotero’ as people used to vernacularise ‘cocktail’.

The beer was expensive, it was somewhat costly to be allowed to enter the bar. But one found the poor Africans struggling to get suits and ties in order to make it into the ‘kokotero’. In fact, it seemed, the tie was the only important item of clothing that enabled one to pass as a ‘gentleman’ at the entrance.

The kokotero was not the only way to get around the the colonial prohibition of African consumption of ‘European beer’ and the evening curfew for Africans. Jazz performer August Musarurwa flagrantly flouted the laws and dramatised Africans’s defiant production and consumption of criminalised home brew with his popular self-composed song ‘Skokiaan’, which would go on to be recorded and performed by Louis Armstrong and Hugh Masekela.

If not at the beer-halls or the kokotero, entertainment could also be found at the ‘native recreation hall’, a feature of all the major townships in Southern Rhodesia, which became the centre of African life. Bulawayo’s Makokoba had Stanley, Salisbury’s Harare African township (now Mbare) had Stoddart, Salisbury’s Highfield had Cyril Jennings, Umtali’s Sakubva had Beit Hall.

Across the colony, on Sundays after long work weeks, subversive ‘tea parties’ and ‘mabhavadeyi’ (birthday parties) were held under a respectable guise by the African elite, and for the working class, who did less to shun traditional ways of life, ‘mahobohobo’ parties were organised in the open air. In contrast to the stiffness of the kwaya (choral music) and township jazz performed at the concerts in recreation halls, mahobohobo gatherings saw the production of a new genre of urban music called masaka, and the flouting of colonial puritanism as women and men interacted freely to provocative women’s urban ‘folk’ songs such as ‘Aya Mahobho Andakakuchengetera’ (‘Here they are, big breasts and buttocks that I am keeping for you’). The song was sung to men by women, who pointed at their breasts, buttocks and vaginas during carnivalesque festivities of merriment. In his 1978 novel The House of Hunger, Dambudzo Marechera draws on the vulgar language of this song—to him, an index of the degraded conditions under which black people in Rhodesia lived—writing that ‘Kushure kwehure kunotambatamba’ (‘the buttocks of the whore shake’).

Such provocative women’s ‘folk’ songs followed in the subversive urban traditions of genres like jikinyira and mavingu, which were rooted in the complaint-based genres first transported to the city in the nineteen-forties by rural black women who sought creative ways to air their many grievances against colonial officials and African patriarchs, as well as powerful rural matriarchs such as mothers-in-law. In the nineteen-forties, ‘Vamwene Vangu’ (‘My mother-in-law’) was an instant hit at the mahobohobo parties. In it, a woman is fed up and is preparing to run away from her mother-in-law who is obsessed with extracting as much labour from her as possible and curtailing her ‘loose’ ways. A popular song in the nineteen-fifties was ‘Zirume Riye’ (‘That lazy man’), in which an African woman complains of a layabout man who follows her everywhere instead of securing employment like other men in the booming manufacturing industry. Together, these women’s ‘folk’ songs were emblematic of the ways in which, as Lawrence Vambe argues in ‘“Aya Mahobo”: Migrant labour and the cultural semiotics of Harare (Mbare) African township, 1930–1970’,

black women wove narratives that not only interrogated the new urban modernity but also critiqued African patriarchy whose material base was itself being eroded by colonial urbanism. In these ways black women altered colonial architecture from its initial intentions in ways that have left permanent physical imprints and spiritual signatures in the city.

As the broader political tensions in the country began to intensify, the usual Sunday pastimes of church, drinking and courtship at ‘tea parties’, ‘mabhavadeyi’ and ‘mahobohobo’ parties gave way to political rallies and meetings, often held in the recreation halls and organised by the firebrand young nationalists of the day. Former nationalist leader Nathan Shamuyarira recalls, in his 1965 memoir Crisis in Zimbabwe, how the nationalist leaders, deliberately shunning the Western ways encouraged for Africans in township life, revived a sort of traditionalism as ‘thudding drums, ululation by women dressed in national costumes, and ancestral prayers began to feature at meetings more prominently than before’. 3 December 1962 saw ‘one huge, coiled black snake of wriggling bodies heading for the central Cyril Jennings Hall’ of Salisbury’s Highfields township, leading to this memorable scene:

At the hall, Youth Leaguers ordered attendants to remove their shoes, ties and jackets, as one of the first signs in rejecting European civilisation. Water served in traditional water-pots replaced Coca-Cola kiosks. By the time the first speaker, a European in bare feet, took the platform, the whole square was a sea of some 15,000 to 20,000 cheering and cheerful black faces. The emotional impact of such gatherings went far beyond claiming to rule the country—it was an ordinary man’s participation in creating something new, a new nation.

Before the rise of ‘mass nationalism’ in the townships in the nineteen-sixties, there were important changes in popularly broadcast music, even as it strained under the controlling efforts of the settler regime. If the township’s loudspeakers were not summoning residents to the superintendents’ offices, calling for the parents of lost children, or blasting propaganda from the Central African Broadcasting Service and later the Federation Broadcasting Corporation, the loudspeaker would play ‘tribal music’ alongside international hits of the day—the likes of Elvis Presley, Cliff Richard, the Manhattan Brothers, Louis Armstrong and Miriam Makeba; and ‘modern’ Rhodesian acts such as De Black Evening Follies and the City Quads would perform live music largely comprising kwaya adapted from the missions, township jazz and increasingly ‘copyrights’ (covers) of popular American music. Singing was not a respectable thing for an educated woman to do, however, so there were few women performers at the time: Evelyn Juba, Virginia Sillah and Lina Mattaka. In particular, Lina Mattaka, wife to a respected musician and daughter of a pastor, personifies the respectable ‘modern girl’ who strived to attain status and express herself through both education and the patronage environment of ‘progressive’ male guardians. She and her husband became the matriarch and patriarch of Zimbabwean township music.

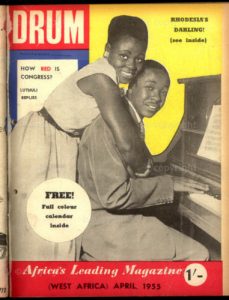

Spurning this model of respectable African womanhood was a young woman who had once been under the wing of the Mattakas—Dorothy Masuka. In 1953, Masuka scored her first big hit with ‘Hamba Nontsokolo’, a song that cemented her status as an artist who had early on distinguished herself on the Rhodesian music circuit by discarding the ‘copyrights’ and, in the tradition of urban women’s ‘folk’ songs, performing original music infused with her own life experiences and the local sounds of the region. She amplified the potency of this by capitalising on and transgressing the patriarchal Victorian and African gender conventions, boldly expressing herself beyond the mere adoptive repertoires of colonial modernity. In 1955, a coy Masuka was featured on the cover of Drum magazine, and declared as ‘Rhodesia’s Darling’. As the fifties progressed, Bulawayo’s Dorothy Masuka and Sophiatown’s Dolly Rathebe were more popular than most male vocal quartets. As the decade increasingly became a time of feminisation of fashion and dance, Masuka and her contemporaries were not only models, but also the composers and choreographers of the song and dances that offended the kind of missionary paternalism embodied by the likes of Kenneth Mattaka, who spurned the irreverent boldness of ‘naughty’ performers who went to mabhavadheyi and mahobo parties to dance, and sell and drink beer.

African Music, Power and Being in Colonial Zimbabwe

by Mhoze Chikowero)

In the year ‘Hamba Nontsokolo’ was released, 1953, Masuka joined many ‘tribal’ and and ‘modern’ African singers and dancing groups—including the Jazz Revellers, the Bulawayo Golden Rhythm Crooners, De Black Evening Follies and South Africa’s Manhattan Brothers—in participating in the ‘African Village’ section of The Rhodes Centenary Exhibition (RCE). Staged in Bulawayo in July and August 1953, and attended by the Queen Mother and Princess Margaret, the RCE was, as music and cultural historian Mhoze Chikowero describes in African Music, Power and Being in Colonial Zimbabwe (2015), ‘a poignant ritual exhibition of imperial domination that also illustrated African contestation of imperial spectacle’. Many African leaders were suspicious of the ill-fated Federation of Rhodesia’s notion of a horse and rider ‘racial partnership’ and urged people to boycott the festival. At that time, however, the eighteen-year-old Masuka did not express any reservations and would in fact go on to be crowned ‘Miss Mzilikazi’ in the RCE beauty contest, which the Follies and the Manhattan Brothers from Soweto also co-sponsored. Just seven years later, Masuka’s increasingly militant consciousness saw her join August Musarurwa, the Jairos Jiri Choir, and Louis Armstrong in refusing to record and sing white-composed songs promoting the Federation.

As predicted by African Parade magazine at the time, the young Masuka was destined for international superstardom. Where her former mentor Kenneth Mattaka, who had toured Africa as far as the Congo, was repulsed by South Africa’s ‘sinful’ image, Masuka took a shine to the City of Gold.

4. eGoli’s ‘good-time girls’

After an assignment to work on cadavers unnerved her, Masuka left nursing school in Johannesburg—the quintessential gateway to ‘modern’ African womanhood in Southern Africa—and hit the sinful Sophiatown music scene, just as South Africa was undergoing major cultural and political shifts, as the newly elected Nationalist Party officially implemented its policy of apartheid. Despite the implementation of the Natives Resettlement Act (1954), which culminated in the forcible removal of 57,000 Africans from multiracial areas such as Sophiatown, Martindale, Newclare and Pageview to Meadowlands and Diepkloof, Johannesburg townships’s half-a-million strong urban African population increased by 50,000 between 1946 and 1959. The popularity of the propaganda musical film Jim Comes to Jo’burg (1949) solidified the dream of glittering gold that lured many young men and women such as Masuka from across the country and beyond the Limpopo.

Masuka’s contemporary Dolly Rathebe, the singing sensation of Jim Comes to Jo’burg, would become emblematic of the ‘Modern Miss’, the ‘Modern African Miss’, or the ‘good-time girl’. Famed Drum writer Can Themba often narrativised the image of this township woman, who was both vital and threatening to the urban African male, and wrote of Rathebe saying:

It is true that she has had a tempestuous life. Men have floated in and out of it, some as gloomy spectres, some as rogues, some as vital, effervescent boilers. She has known and lived the violence and sordidness and stink of township life. She has drunk … and found in vino veritas, the tot of truth. People have called her all sorts of names, those who thought they were entitled to cast the first stone. But somehow none of these things stuck … If she has been a she-devil, that’s because she’s a helluva woman!

‘Feisty’ women, whether mothers, ‘Shebeen Queens’, lovers, wives, beer brewers, night club singers or ‘good-time girls’ were often depicted in the literature of the times. Themba’s short story ‘Marta’ features a once-loved and now abused ‘good-time girl’, drunk on a Monday morning, passing a bus stop:

Her baby was hanging dangerously on her back as she staggered up Victoria Road. Somebody in the queue remarked dryly, ‘S’funny how a drunk woman’s chile never falls.’

‘Shet-up!’ said Marta in the one vulgar word she knew.

She stood, swaying moment on her heels, and watched the people in the queue bitterly. A bus swung round the Gibson Street corner and narrowly missed hitting her. Three or four women in the queue screamed, ‘Oooo!’ But Marta just turned and staggered off into Gibson street, the child carelessly hanging on her back.

Subsequently, Marta is nearly strangled to death by her adulterous husband when he discovers her in her drunken state. On waking up from her stupor, she is met by a group of friends—including a man and two other good-time girls—who persuade her to go to a shebeen around the corner. While at the shebeen she dances to a stirring jazz solo of drums played by a teenage boy whom she eventually asks to escort her home. As they walk, she begs the young drummer she adores, ‘Look here, kid, I want you to promise me one thing. Promise me that you will never drink.’ The story ends with Marta relating to her friend how her husband had killed the teenage drummer he wrongly believes to be her lover. The final sentence thus ironically reads, ‘The drunk woman’s child has fallen.’

Like Dhlomo’s An African Tragedy, Themba’s story clearly depicts the anxiety that existed over the sexual behaviour of the ‘good-time girl’—an urban black woman who was simultaneously vital and threatening to the identity of urban black men. Arguably, Themba shows this anxiety most powerfully in his canonical short story ‘The Suit’, in which Philemon is so tormented by the possibility of his wife’s infidelity that he chooses the unequivocally sadistic punishment of having her serve an inanimate suit, indefinitely.

Standing in contrast to the image of the loose young woman of the townships is the capable, tough, ‘two-hundred pound weight’ entrepreneurial ‘Shebeen Queen’ Aunt Peggy depicted in ‘On the Beat’, the fictional series of Themba’s former student, Casey Motsisi. Aunt Peggy is authoritative and officious as she wobbles across the floor, her ‘beefy right arm’ held out, calling, ‘Money on the table first … or else.’ As Hugh Masekela once quipped, in Sophiatown ‘every third house was a shebeen!’ The ‘Shebeen Queen’ was a township matriarch who personified defiance of colonial urban authority and the adoptive African middle-class notions of respectability.

Linked to the anxiety over the sexuality of the ‘good-time girl’ was the anxiety over her looks. As the use of cosmetics began to spread amongst African women, the image of the ‘painted woman’ as ‘prostituting woman’ gained currency. While the black elite’s ‘economic proximity to black lower class created possibilities for, as JT Campbell describes in his text ‘TD Mweli Skota and the making and unmaking of a Black Elite (1987), ‘downward identification’ and ‘radicalisation’, it also created the ‘need for mechanisms which maintained social distance, which emphasised status within the racial caste’. Thus, the fact that cosmetics were used most ‘freely’ by African women of lesser social distinction saw ‘AmaRespectable’ men such as The Bantu World editor RRR Dhlomo, concerned as they were with class distinction, caution against the use of cosmetics, citing the ‘cheapness’ of the look. Cosmetics use became one of the most contentious issues surrounding the modern black woman because it drew attention to the phenotypic dimensions of racial distinctions’, and Dhlomo admonished African women by saying that they ‘should abandon their desire to turn themselves white’.

This is in line with the placement of the burden of race purity and authenticity on African women, particularly within the context of nationalisms, modernity, culture and identity. (The kind of problematic notion taken up by the late Hugh Masekela, who famously refused to take pictures with women who wore weaves.) There are resonances between nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century colonial photography that framed African women as erotic subjects and the photography of African women within the pages of The Bantu World newspaper. Thema’s desire to prove, presumably to a white colonial gaze that has framed Africans in general and African women in particular as unattractive, that ‘there are beautiful women and girls in Africa’ (having previously justified the paper’s new attention to women saying ‘no nation can rise above its womenfolk’) through the establishment of a magazine beauty contest, as well by championing of the ‘Miss Africa contest’, translated into the imaging of African women on the publication’s pages with what Laura Mulvey calls a ‘to-be-looked-at-ness’.

Masuka and her peers, such as Dolly Rathebe and Miriam Makeba, capitalised on and subverted this male centred ‘to-be-looked-at-ness’. Their recurring images on the covers and pages of Drum demonstrate the power of their self-imaging and self-styling, even when it was deemed threatening to patriarchal nationalist ideals. They visiblised themselves, pushing past the African male writers’ anxieties and into their popular texts and images (not to mention the films). In other words, nomakanjani, whether African male writers were made anxious by these new African women, whether they liked them or not, they had to deal with them and could not erase their presence in this modern African cityscape. While the effect of this was often problematic patriarchal narrativising, the fact of the ‘good-time girl’s’ presence is undeniable.

And so, combining the provocative image that had won her the Miss Mzilikazi crown and pages within South Africa’s Drum and Rhodesia’s African Parade, with her original self-composed songs and unique voice, Masuka catapulted herself to the top of a community of women singers that music historians Chitauro, Dube and Gunner described in their seminal 1994 text ‘Song, Story and Nation’ as forming

the vibrant black urban culture of the fifties which had Sophiatown as its hub but spread much further afield and was linked through record sales, radio and concert tours to urban centres such as Salisbury and Bulawayo and other towns of the Northern Rhodesian copperbelt.

By then, Masuka’s contemporaries in this transnational musical sorority included the Zimbabweans Faith Dauti and Susan Chenjerai, and Miriam ‘Mama Africa’ Makeba, Dolly Rathebe, Letta Mbulu, Thoko Thomo, Susan Gabashane, Thandi Klaasen and Sophie Mgcina. Some of these songstresses, especially Makeba and the jazz crooner Hugh Masekela, rose to fame partly by doing renditions of Masuka’s compositions. As Makeba wrote in her 2004 autobiography, Makeba: The Miriam Makeba Story, ‘[Masuka] wrote, sang and taught me many beautiful songs that I sang many times throughout my career.’

But Masuka had to conquer the vices of eGoli’s misogynistic and xenophobic entertainment circles. In April 1959 she told African Parade how inhospitably the city had ‘welcomed’ her during her debut at Alexandra’s King’s Theatre:

When I got on to the stage, the house was nice and fat, but as soon as it was learned that I was a Rhodesian, there were some booes and shouts of Kilimane!—a derogatory term by which our black brethren in the Union sometimes call us we who come from across the Limpopo River.

Masuka refused to be intimidated and claimed space in her audience’s heart with her song ‘Ndizulazula eGoli’. From that bold start, she toured extensively with the African Inkspots, the Manhattan Brothers, the Woodpeckers and the Harlem Swingsters, among others, and propelled herself to stardom through socially and politically conscious compositions that weaved African traditional expressive styles into the jive idiom.

Masuka’s rapid success as a ‘foreign’ female performer made her vulnerable to the underworld of zoot-suited and tsotsitaal-speaking gangsters and klevas. Fortunately, she had anticipated such trouble and surrounded herself with her own ‘boys’. As Makeba also noted in her autobiography, it was an era in which it was understood that ‘every gangster had to have a glamorous girl and every performer had to have a gangster (whether you liked him or not)’ and so, Makeba, Masuka and their contemporaries often suffered the ‘protection’ of these klevas, including routine kidnappings, stabbings and assaults.

Ever the ‘good-time girl’, after Masuka caused a furore by grabbing the attention of ‘the man to talk about in town’ on her maiden Cape Town tour with the Harlem Swingsters, she narrativised the social havoc she had triggered in her hit ‘Pata Pata’—which Makeba, Masekela and most recently Oliver Mtukudzi and the Afro Tenors all recorded. Echoing the sexual innuendo of the urban women’s ‘folk’ song ‘Aya Mahobho’, ‘Pata Pata’ signified the disruption referred to at the start of this essay: ‘good-time girls’ stirring things up as they swayed enticingly along the pavements of the townships. This and other songs, such as ‘Khauleza’, not only helped to launch and propel the careers of artists like Masuka, Makeba and Masekela; they also helped to spur on the new music craze, called kwela, based on the pennywhistle sounds pioneered by the likes of Spokes Mashiyane and Lemmy ‘Special’ Mabaso.

As was the case with Musarurwa’s ‘Skokiaan’ and the urban women’s ‘folk’ song ‘Aya Mahobho’, kwela was a metaphor for Africans’ encounters with the criminalisation of their urbanity and of their subversive survival strategies. ‘Kwela’ as it is known in Zulu, or ‘kwira’ as it is known in Shona, came to be shorthand for the all-too-often-heard command to climb into waiting police jeeps. Kwela was the subversive mimicry of the banal violence that settler police unleashed on the township’s female brewers and street hawkers as they exacted fines and other punishments. African women clasped the word and instilled in it a new significance so that, in the performance, the simulated ‘touching all over the body’ parodied the invasive body searches.

The kwela performative register was deeply implicated in the more complex gendered political economy of the underclass shebeen subculture. Through songs like ‘Khauleza’, Masuka dramatised the battles of underclass urban black women, particularly the ‘Shebeen Queens’ and backyard brewers of Skokiaan, as they stood against alcohol laws and police harassment. As Makeba explains in her autobiography, staging a powerful critique of apartheid as Masuka did demanded uncommon courage in an era when record companies colluded with the state to silence artists:

There were a few black people, so-called ‘talent scouts’, who worked for record labels. Their job would be to report us if we dared sing anything considered seditious. We could not sing anything political, which meant we could rarely sing anything directly saying what was really happening to us in our lives. It took artists like Dorothy Masuka, who was bravely singing Khauleza—saying, ‘Hurry mama, Hurry mama, Hurry up and hide because the police are coming!’

5. ‘O! Nolishwa!’

Like the urban African women who sang ‘Aya Mahobo’ and ‘Zvirume Riye’, Masuka’s ‘sextual/textual politics’ (Khan, 2008) creatively utilised these aporic tensions to inform a complex, politically conscious African agency that directly engaged the realities of its feminised colonised being. Masuka herself, easily described as a ‘good-time girl’, represented a particular form of transgressive new African womanhood, combining self-imaging in the tradition of glamorous female jazz performers with self-writing through the composition of explicitly political songs, such as the banned ‘Dr Malan’. Contesting the patriarchal gaze of both the settler state and African society, Dorothy Masuka’s ‘Nolishwa’ (1956) stands exemplary of the work of African women at the time. The song astutely reflects the personal-political through the use of two voices, namely a conservative and critical communal voice and the voice of Nolishwa’s boyfriend:

Oh! No, Nolishwa is surprising

Oh! No, she is so proud.

Oh! She stands on her own strong feet and I love her more for that.

You say you saw her with another boyfriend

But I love her as she is.

Honestly, I saw her with another man yesterday

And she was wearing trousers.

With another man and wearing trousers?

I love her still like that.

In this relatively overlooked song lay a deceptively simple story about an African woman who wore trousers and was seen around with men, which highlighted the intensifying struggle over African women’s mobility and sexuality in Southern Africa’s heavily-policed and regulated urban centres.

‘Nolishwa’ is particularly notable for its representation of a masculinity that is accepting of transgressive African femininity. Nolishwa could very well be read by the likes of Can Themba as a ‘good-time girl’, by virtue of her dressing in trousers and being seen in public by men who are not her boyfriend, and yet her boyfriend continuously remarks ‘But I love her as she is’, ‘I love her like that’. Unlike Marta’s husband, who is simultaneously attracted to and repelled by her ‘good-time girl’ behaviour, Nolishwa’s boyfriend is seemingly secure and not faced with a crisis of reconciliation. He is content with his ‘good-time girl’. Masuka thus shows us that a man, and by extension society at large, need not be so vexed or even ‘destroyed’ by the good-time girl. They need only ‘love her like that’. While the urbanising societies in which Marta, Nolishwa and their partners live have the same attitudes towards ‘good-time girls’, Nolishwa’s boyfriend stands in contrast to the figure of Marta’s husband, who, unable to control his wife’s behaviour, almost strangles her to death and later, unable to face the idea of her possible infidelity, intimated by her ‘standing with another man’, is led to kill the ‘other man’. We can imagine that if Nolishwa’s boyfriend were to meet with the same scenarios he would simply remark, ‘But I love her as she is’, ‘I love her like that’.

And so, Masuka’s composition was an important counterpoint to the figure of the ‘good-time girl’ as she was imagined by the male writers and consumers of popular print culture. In the Drum era, when reportage and short stories were an important chronicler of urban black South African life, the instances of African women’s self-writing in the pages of popular consumer publications were few and far between. Very often, as literary critic Obioma Nnaemeka argues of female fiction writing across the broader African continent, African women’s self-writing appeared in liminal spaces mediated by the knowledge of the male gaze as reader/critic. While Themba’s story of the once loved and now abused ‘good-time girl’ Marta may be read as merely ‘telling it like it is’, Masuka’s narrative offers a more emancipatory and liberatory vision for the ‘good-time girl’ to be ‘loved as she is.’

Beyond this, highlighting the timing of the release of ‘Nolishwa’ is also critical to understanding the deceptively simple song’s power in underscoring the tug of war between the wills of African men and women in Southern Africa’s urbanising settler colonies. In the nineteen-thirties, even as some African patriarchs colluded with the colonial state to introduce passes restricting African women’s movement in Rhodesia’s urban areas, African women held their space, organising campaigns, such as the 1934 Beer Hall Boycott, on their own or alongside their male counterparts. In 1956, the year ‘Nolishwa’ was released, African women living in Carter House hostel in Harare African township, now Mbare, were raped by male workers as ‘punishment’ for breaking the Salisbury Bus Boycott led by the newly formed City Youth League, the party that would be the home of young firebrand leaders such as Robert Mugabe, George Nyandoro and Edson Sithole. The women who had broken solidarity by using the buses to go to work in Salisbury, many as domestic workers and secretaries, were reportedly seen as black ‘prostitutes’ who, because of their high service fees, could afford the bus fares that were being protested. The violence provoked an unnamed mother to ask, ‘raping my daughter, is that the Bus Boycott?’ It was not surprising when The Daily News reported: ‘Harari [sic] residents enjoyed their usual Friday night dance in the recreation hall last night … fewer girls attended. This was the first dance after the riots on Monday.’ Forcing women to retreat from public space was exactly what was intended.

In the same year, just south of the Limpopo River, 20,000 women across racial lines marched to the seat of the apartheid government, Pretoria’s Union Buildings, to present a petition against passes for black women to then-Prime Minister JG Strijdom. In Women and Resistance in South Africa (1991), Cheryl Walker describes the impressive visual scene as the women filled the entire amphitheatre of the building:

Many of the African women wore traditional dress, others wore the Congress colours, green, black and gold; Indian women were clothed in white saris. Many women had babies on their backs and some domestic workers brought their white employers’ children along with them. Throughout the demonstration the huge crowd displayed a discipline and dignity that was deeply impressive.

Neither the prime minister nor any of his senior staff were there to see the women, so, as they had done the previous year, the leaders left the huge bundles of signed petitions outside Strijdom’s office door. The petition, drafted by the Federation of South African Women and the Indian Youth Congress, read as follows:

We, the women of South Africa, have come here today. We African women know too well the effect this law upon our homes, our children. We, who are not African women know how our sisters suffer. For to us, an insult to African women is an insult to all women.

That homes will be broken up when women are arrested under pass laws.

That women and young girls will be exposed to humiliation and degradation at the hands of pass-searching policemen.

That women will lose their right to move freely from one place to another.

We, voters and voteless, call upon your government not to issue passes to African women. We shall not rest until we have won for our children their fundamental rights of freedom, justice and security.

With a keen eye for political performance, Lilian Masediba Ngoyi, the staunch anti-apartheid activist who was the first woman elected to the ANC national executive committee, led the huge crowd, which had stood in absolute silence for a full half hour, in singing the African nationalist hymn ‘Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika’, followed by the woman’s freedom song ‘Wathint’ Abafazi, Strijdom!’ (‘You strike a woman you strike a rock, Strijdom!’)

Both the Carter House rapes and the 1956 Women’s March and highlight the threat that black women’s mobility, their movement and actions outside of male control, posed to the settler state and African patriarchs alike.

Together, early urban African women’s ‘folk’ songs, Masuka’s compositions, petitions and the protests can be seen as exemplary of what literary critic Susan Andrade in her seminal 2002 text ‘Gender and ‘the public sphere’ in Africa: writing women and rioting women’ identified as ‘writing and rioting women authors’ in Africa’s public spheres. Critically, Andrade argues that:

at a moment when the cultural production and political agitation of men were easily assimilated into a nationalist paradigm, women’s culture and politics were often understood as unrelated to nationalism, and therefore, as not engaged in the larger political process. Nationalism, the most visible macropolitical discourse of the continent at the moment of decolonisation, appears to occlude women’s political involvement.

Andrade argues that examining the actions of the two different classes of women—namely ‘writing women’ (‘middle class women writing novels’), and ‘rioting women’ (‘plebian women engaging in rebellions and uprising’)—in relation to each other and to ideas of the public civil sphere allows a reconception of this sphere, civil society and women’s engagement with decolonising nationalism.

We can re-examine African women’s actions in relation to both each other and the public sphere and complicate Andrade’s categorisations of ‘writing’ and ‘rioting’ women. In the first instance, the ‘writing woman’ should not only comprise ‘middle class women writing novels’ but should also privilege the contributions of women writers of a wider variety of texts, including oral texts and the individual compositions of women like Dorothy Masuka, who was a prolific songwriter, and the collective compositions of urban working women, such as ‘Aya Mahobo’ and ‘Wathint’ Abafazi, Strijdom!’ Likewise, the drafting of the petitions and manifestos, as had been done by the Federation of South African Women, forms part of the expanded categorisation of ‘writing women’. In the second, ‘rioting’ should not be limited to ‘rebellions and uprising’; Masuka staged protests through her music, and was considered such a threat to the settler colonial order in South Africa and Rhodesia that she was forced into exile several times. Similarly, Masuka’s songs such as ‘Pata Pata’ and ‘Nolishwa’ were deemed an affront to respectable African middle-class values. Further to this, the body, particularly the body acting, whether in dance or protest, or indeed both, may read as text too. And so, the dancing of the ‘mahobohobo’, the ‘pata pata’, the ‘kwela/kira’, as well as the Carter House hostel women’s defiance of the bus boycotts, the 1956 Women’s Marchers’s thirty minutes of standing silence, the Women’s Marchers’s appearance in African attire at the seat of the racist apartheid government, can be read as texts which African women have authored in the public sphere.

And so, when the dichotomy between writing and rioting is collapsed, it becomes clear that through the composition and performance of transgressive songs such as ‘Nolishwa’, ‘Khauleza’, ‘Aya Mahobo’, ‘Wathint’ Abafazi, Strijdom!’, the drafting of petitions and the staging of protest action such as the beer-hall boycotts and the Women’s March, black women were able to weave narratives that interrogated both the banalities and extremities of life in Southern Africa’s urban centres, simultaneously critiquing settler authorities, the conservative African middle class and patriarchal nationalists. In this way, women such as Masuka, the beer-hall boycotters and the 1956 marchers can all be understood as ‘(w)ri(o)ting’ women, whose words, actions, songs and performances come together to contest both dominant narratives and structures of racialised and gendered orders.

Masuka’s ‘Nolishwa’ therefore exemplifies the subversive mode of ‘(w)ri(o)ting’ that did not easily assimilate into the dominant nationalist paradigm of the nineteen-fifties Southern Africa. Through the song Masuka subtly, and yet very powerfully, underscored the ‘micro–macro’ or personal–political issues of love, courtship and sexuality presented by the ‘good-time girls’ such as herself and her peers Dolly Rathebe and Miriam Makeba, who were simultaneously threatening and vitalising to the urban African man and broader settler colonial society.

6. ‘My voice was as powerful as a gun’

As Masuka’s growing reputation as a powerful ‘(w)ri(o)ting’ woman saw her increasingly hounded across settler borders she drew on her defiant Pan-African political consciousness to defy colonial authority.

The apartheid government expelled Masuka from South Africa when she composed ‘Malan’ after the Sharpeville Massacre. Remarking on the censorship of this and many of her other songs in the docu-musical Sophiatown: Surviving Apartheid, Masuka memorably laughed, saying: ‘They should have destroyed me instead; because I can still sing.’

In a follow-up song, composed while she was in Bulawayo in 1961, Masuka extolled Patrice Lumumba in a song of the same name, ‘Lumumba’. For Masuka and many other anti-colonial activists, the Congolese Pan-African hero, after whom Masuka named her own son, represented the dawn of a new postcolonial Africa, the antithesis to the white settler regimes of the region. This song would force her into exile again.

Masuka set off for England, where she was at one time marginally involved with the touring South African jazz opera King Kong. She appeared on the BBC’s Channel 2 and at some nightclubs in London’s West End. In time, African Parade (January 1961) would declare that her songs were being ‘sold [at home] and [in London] with a speed that defie[d] all past African records’, and that Masuka was Southern Rhodesia’s ‘ambassador, just like Louis “Satchmo” Armstrong for the Americans’. Importantly, ever a self-authoring woman conscious of crafting her image, Masuka was adamant that her career trajectory did not depend on the stereotyping, exoticising, racially-overdetermined entertainment circuits of European capitals, saying: ‘I have turned down some offers because I don’t want to appear in shows where there are strip-teasers.’

Back on African soil, Masuka would make homes of Malawi and Tanzania between 1961 and 1965. In 1965, she went back to Bulawayo, but had to flee to Zambia. She would only return to Zimbabwe when it became independent in 1980. Throughout her exile, the persecution Masuka faced buoyed her spirits as a ‘(w)ri(o)ting’ woman whose voice soared beyond the confines of the settler state, as she travelled the continent with the region’s nationalist leaders, performing on platforms such as the Organisation of African Unity’s Pan-African Cultural Festival of Algiers in 1969. In a 2005 interview in The Herald, Masuka would say of her (w)ri(o)ting legacy:

I never held a gun but my voice was as powerful as a gun. It took me a few moments to send my revolutionary messages home to millions of people. When I sang ‘Tinogara Musango’ [We live in the bush] and ‘Dr Malan’, it was like being with the people.

Long into the post-independence era and the twilight of her career, Dorothy Masuka continued to tour the African continent, where, singing in languages from Shona, Ndebele, Zulu, English and Swahili to Nyanja, Lozi and Bemba, she is claimed by many nations. As music historian Mhoze Chikowero writes, Masuka’s story is

of one woman’s complex identity and aspirations, a tale of a woman who rehumanised herself and helped craft collective futures through mobility and political engagement with colonialism across its arbitrary borders, the chief immobilising instrument of its illegitimate sovereignty.

Indeed, Masuka’s power as ‘(w)ri(o)ting’ woman lay in her ability to deploy tropes of a violent and pleasurable everyday in crafting critical counter-discourses that would ultimately define her as ‘dangerous’ both to the settler regimes, the ‘respectable’ African middle class and the patriarchal nationalists of the day. As a ‘(w)ri(o)ter’ whose voice was truly ‘as powerful as a gun’, Masuka stood both among and apart from other African performers in her ability to draw from the youthful excesses of the shoulder quivers, hip jerks, the ‘pata pata’, the ‘mahobohobo’, the ‘kwela’—the pleasures of being a ‘good-time girl’—in order to redefine independence and freedom by embodying a militant woman-centred Pan-African consciousness, using music as a subversive platform to fight the settler regimes and reclaim all of the continent as her, and indeed our, home.

*

It is to Dorothy Masuka we might turn when we forget that we are not the first. Our mothers have been here before.

Listen. And you will never forget.

~~~

- Contributing Editor Panashe Chigumadzi was born in Zimbabwe and raised in South Africa. Her debut novel Sweet Medicine (Blackbird Books, 2015) won the 2016 K Sello Duiker Literary Award. She is the founding editor of Vanguard magazine. A columnist for The New York Times, her work has featured in titles including The Guardian, Chimurenga, Washington Post and Die Ziet. Her second book, These Bones Will Rise Again, a reflection on Robert Mugabe’s ouster, was published in June 2018 by the Indigo Press. She is a doctoral candidate at Harvard University’s Department of African and African American Studies. Follow her on Twitter.

References

This essay was written with reference to the following texts (although not an exhaustive list):

Andrade, S 2002. ‘Gender and ‘the Public Sphere’ in Africa: Writing Women and Rioting Women Author(s)’ in Agenda: Empowering Women for Gender Equity, No. 54 (2002), pp 45-59.

Barnes, T 1992. ‘The Fight for Control of African Women’s Mobility in Colonial Zimbabwe, 1900-1939’ in Signs, vol. 17 no. (3): pp 586-608.

Becker, R 2000. ‘The New Monument to the Women of South Africa’ in African Arts vol. 33 (4): pp 1–9.

Campbell, JT 1987. ‘TD Mweli Skota and the making and unmaking of a Black Elite’. University of the Witwatersrand History Workshop: The Making of Class. URL: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/39666694.pdf

Chadya, JM 2003. ‘Mother politics: Anti-colonial nationalism and the woman question in Africa’ in Journal of Women’s History vol. 15 no.(3): pp 153–57.

Chapman, M 2001. ‘More than telling a story: Drum and its significance in black South African writing’ in Chapman, M (ed) The Drum Decade: Stories from the 1950s. Durban: University of Kwa-Zulu Natal Press.

Chigumadzi, P 2018. These Bones Will Rise Again. London: The Indigo Press.

Chikowero, M 2015. African Music, Power and Being in Colonial Zimbabwe. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Chitauro, MB, Dube, C, Gunner, E 1994. ‘Song, story and nation: Women as singers and actresses in Zimbabwe’ in Politics and Performance: Theatre, Poetry and Song in Southern Africa, pp 111-38.

Coplan, D 2008. In Township Tonight: South Africa’s Black City Music And Theatre. Johannesburg: Jacana Media.

Foster, T 2014. ‘On creativity in African urban life: African cities as sites of creativity’ in Stephanie Newell and Onookome Okome (eds) Popular Culture in Africa: The Episteme of the Everyday. New York: Routledge.

Gamanya, HD 2009. Guerilla Girl: A Girl’s Echoing Voice in the Zimbabwe Chimurenga. Bath: Paragon Publishing.

Jaji, T 2014. ‘Bingo: Francophone African women and the rise of the gossy magazine’ in Stephanie Newell and Onookome Okome (eds) Popular Culture in Africa: The Episteme of the Everyday. New York: Routledge.

Jenje-Makwenda, Joyce 2004. Zimbabwe’s Township Music. Harare: Self-published.

Jenje-Makwenda, Joyce 2013. Women Musicians of Zimbabwe—a Celebration of Women’s Struggle for Voice and Artistic Expression. Harare: Self-published.

Khan, K 2008. ‘South-South cultural cooperation: Transnational identities in the music of Dorothy Masuka and Miriam Makeba’ in Muziki: Journal of Music Research in Africa, vol. (5) 1: pp 145–51.

Legoabe, L 2006. ‘The Women’s March 50 years later: Challenges for young women’ in Agenda: Empowering Women for Gender Equity, vol. 69 (21): 143–151.

Makeba, M 2004. Makeba: The Miriam Makeba Story. Johannesburg: STE Publishers.

Masuka, D 1956. ‘Nolishwa’ in Daymond, MJ et al (eds) 2003 Women Writing Africa: The Southern Region. Johannesburg: Wits University Press. pp 245–46.

Metrowich, F 1969. Rhodesia: Birth of a Nation. Africa Institute of South Africa.

Mlambo, AS and Raftapoulos, B (eds) 2009. Becoming Zimbabwe: A History from the Pre-colonial Period to 2008. Harare: Weaver Press.

Mutongi, K 2000. ‘”Dear Dolly’s” advice: Representations of youth, courtship and sexualities in Africa, 1960–1980’ in The International Journal of African Historical Studies, vol.33 (1): pp 1–23.

Nnaemeka, O 1994. ‘From orality to writing: African women writers and the (re)inscription of womanhood’ in Research in African Literatures, vol. 25 (4): pp 137–157.

Samuelson, M 2013. ‘The urban palimpsest: Re-presenting Sophiatown’ in Ranka Primorac (ed) African City Textualities. London: Routledge.

Shamuyarira, N 1965. Crisis in Zimbabwe. London: Andre Deutsch.

Sithole, N 1968. African Nationalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Smuts, JC 1930. Africa and Some World Problems. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Staunton, I (ed.). 1990. Mothers of the Revolution: The War Experiences of Thirty Zimbabwean Women. Harare: Baobab Books.

Themba, C 2001. ‘Marta’ in Chapman, M 2001. The Drum Decade: Stories from the 1950s. Durban: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press.

Thomas, LM (2008) ‘The Modern Girl and Racial Respectability in 1930s South Africa’ in Alys Eve Weinbaum et al. (eds) The Modern Girl Around the World: Consumption, Modernity, and Globalisation. Durham: Duke University Press.

Vambe, MT 2007. ‘”Aya Mahobo”: Migrant labour and the cultural semiotics of Harare (Mbare) African township, 1930–1970’ in African Identities, vol. 5(3): pp 355–369.

Walker, C 1991. Women and Resistance in South Africa. New Africa Books.

Yoshikuni, T 2007. African urban experiences in colonial Zimbabwe: A social history of Harare before 1925. Harare: Weaver Press.

Newsletters and Newspapers

These periodicals are cited in the text:

African Parade

The Herald