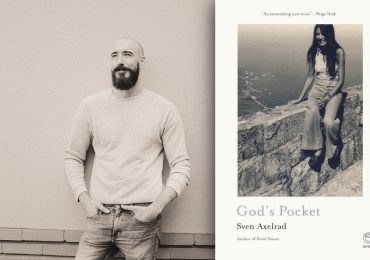

As part of our January Conversation Issue, The JRB Editor Jennifer Malec talks to Siphiwe Gloria Ndlovu about her debut novel, The Theory of Flight.

The Theory of Flight

The Theory of Flight

Siphiwe Gloria Ndlovu

Penguin Random House, 2018

The JRB: The Theory of Flight is your debut novel, but in a lot of ways it’s an atypical debut. It’s not recognisably a veiled autobiography, and it’s quite ambitious, in character and theme. How did it develop?

Siphiwe Gloria Ndlovu: I used to write screenplays in film school, and then I wrote my dissertation, but this is the first fictional manuscript that I started and finished writing. It was a long process, it took several years, because I had other things to do in between. Some parts of it are autobiographical, like the childhood scenes. The whole novel is my thinking around love and loss, because I lost someone very dear to me to HIV, so it was my way of thinking through that and figuring out what that loss means. So there’s definitely those elements. I think it also has a lot to do with my preoccupation with history, and the legacies of certain histories and violence.

The JRB: The book has been hailed for its ‘magic’ and is often cited as an example of ‘magical realism’, but it didn’t really strike me that way at all. Did you feel you were writing magical realism?

Siphiwe Gloria Ndlovu: I understand why people would categorise it like that, because Genie, the main character, does fly, and I think people see these kinds of things as existing outside of realist fiction, so when they’re there they just assume that’s what it is. I don’t necessarily agree with the label, for several reasons. Those categories make it seem that in your imagination there are these boundaries, but I think in your imagination anything can happen, that’s why we tell stories, because anything can happen in our imaginations. When you start saying this is only possible in this particular genre, that takes away from the imagination. So as a writer I have issues with the category. But as a reader, if I went into a store, I understand why the categories are there. They allow me to know where to go for what I’m looking for.

There is a way of thinking about certain types of writing that boxes them off, and when people see things that don’t happen in the rational, normal world, it must be this other thing. I don’t think that. I also don’t remember receiving stories that way myself. Stories when I was a child were just stories. I lived in a place where for a good part of my childhood one of the main stories was this ghost that would entice married men at night, and this was being published in the newspaper. No one was saying, ‘Oh, this is a ghost story.’ It was just a story, and we were all reading it. It’s not like we one hundred per cent believed it, but we understood that that was just how people told stories. There wasn’t this feeling of, ‘Oh, this is a newspaper, so it will only cover facts.’ Those boundaries just don’t exist for me when I’m thinking of a story. They may exist intellectually but definitely not creatively.

The JRB: Having said that it didn’t strike me as magical realism, the novel begins with a family history, which for me was reminiscent of Gabriel García Márquez. Were you influenced by Márquez at all?

Siphiwe Gloria Ndlovu: The truth is, and I did this very intentionally, when I started writing the novel and I sent it out, one of the reader’s notes was—’This is very Márquez-like’, which is good to hear, because it’s Márquez, right? I’d read Chronicle of a Death Foretold, but not One Hundred Years of Solitude, and I decided I wasn’t going to read it until I was done writing, and then there’s no influence. Then when I read it I was like—Wow. I don’t even know how he did it, it’s the best novel ever. There may be some elements that are the same but I don’t know that anyone else could have squeezed that kind of generational storytelling into just one book. But in terms of Márquez, my novel is part of a group of intersected novels, they feed off of each other. I can’t do it all in one book but in the end it will be this intergenerational series of novels. History really fascinates me, so the way I look at the world is very much about how the people who came before me made choices that then influenced the choices I made, whether I liked it or not. My grandmother choosing to go to a certain school, meeting my grandfather, falling in love, all those things ended up making me. You can’t start a story without saying ‘How does this person come to be?’, in my way of thinking.

The JRB: Was the novel always structured like that, or did you begin with the character and then write the history afterwards?

Siphiwe Gloria Ndlovu: It had a long life. I think because of my film background I would write and then there would be a lot of flashbacks within a character’s story. But that was very confusing. And when I realised that wasn’t working I thought, okay, why don’t I just write it as a history. Take all these things that happened before, put them where they belong, and then just tell the story after that. And that worked a lot better. But the history was always there, because I think it’s important to know the genesis of things.

The JRB: The cultural references in the book are both specific to an unnamed southern African country—the Everlasting sweets, Highlanders biscuits, the mapantsula, the Scania pushcarts—but also unapologetically global, or ‘Western’, and here I’m thinking of references to The Carpenters, Dolly Parton and so on. So there’s a very strong sense of place, but at the same time the novel feels somehow more expansive. Was this something you thought about when writing it?

Siphiwe Gloria Ndlovu: That’s a very deep question for a very shallow answer. The truth is, Zimbabwe has had this fascination, from forever, with Dolly Parton. We love her. We were waiting for her, she was supposed to come and give a concert for years, we waited, she never came [laughs]. And Don Williams. There was no household in Zimbabwe that didn’t have their records. We just loved them. Who knows why, music travels. I just remember my childhood was that music, country music.

The JRB: So it’s actually a Zimbabwean cultural reference.

Siphiwe Gloria Ndlovu: Yeah. The eighties were definitely Dolly Parton years. That would not make any Zimbabwean reader raise an eyebrow.

The JRB: Halfway through the book I took a break to watch The Carpenters’s music video for ‘Calling Occupants of Interplanetary Craft’, and it kind of blew my mind. My mother was into The Carpenters but clearly only the early stuff. How did you come across the song?

Siphiwe Gloria Ndlovu: I love that song. Again, from my childhood. The Carpenters were also big in Zimbabwe [laughs]. Fun fact: when we got independence, the first song that played on Radio 3 was a Carpenters song.

The JRB: Was it a revolutionary song—?

Siphiwe Gloria Ndlovu: No. We just really, really love The Carpenters.

The JRB: Because … Bob Marley was there [at the 1980 independence celebrations].

Siphiwe Gloria Ndlovu: We loved him too. But. The Carpenters.

The JRB: At one point in the novel, a Coloured character who has had some success as a sculptor is suddenly deemed ‘“too white” to be a truly postcolonial artist’, and his sculptures are dismantled. This after he has been named, by critics in the press, a ‘truly postcolonial artist’, and then a ‘post-postcolonial’ artist, for reasons he is unsure about. In some ways this book seems to me to be a response to that kind of categorisation that artists, especially African artists, face.

Siphiwe Gloria Ndlovu: I think I wouldn’t know how to write something that’s just an ‘African novel’. Africa exists in the world, and the world has always been in Africa. As Kwame Anthony Appiah points out, even the African fabrics I love to wear are made somewhere else, they’re not made on the African continent. They’ve been called African fabrics for centuries. We’re not the ones who make them but it’s part of who we are. So when you realise that there are all these roots and there’s all this connectivity that has been there for centuries, then you can’t write anything that’s insulated and ‘African’, because that space is already ‘contaminated’—and he uses the word ‘contaminated’ in a good way—it’s already ‘contaminated’ by all this traffic through it. So I don’t think that I’m consciously thinking about making my writing expansive or global, it already is. Music travels and all of a sudden everyone is listening to Dolly Parton. That’s just the world.

In Yvonne Vera’s The Stone Virgins she mentions this song called ‘Skokiaan’. The songwriter came from Bulawayo, where I grew up, and the song travelled all the way to America and became a hit for Louis Armstrong. That’s music. You can’t say there’s that part of the world and there’s this part of the world. Which is why the politics today is interestingly confusing because it’s like, you know that’s not true, right? People don’t just stay static, they don’t not move. And I know that it’s frustrating for some people but that’s just the way the world has always been. I know some people used to talk about how the local is global and vice-versa. But I like the idea of things like travel. Edward Said had this thing called ‘travelling theories’, where once a thing travels, it’s no longer the thing it was. It becomes what it becomes in that new space.

The JRB: Which is why Zimbabwean Dolly Parton is a different thing.

Siphiwe Gloria Ndlovu: Different from the way she’s consumed in America. So for me the world is fluid. Maybe also because I have lived in other places for long periods of time, but I cannot write as if that is not how I see the world and how I experience the world.

The JRB: I feel like a lot of Zimbabweans I’ve known have that worldview.

Siphiwe Gloria Ndlovu: Many of us are now living outside of home, a lot of us are diasporans, wherever we are, so the idea of ‘home’ has had to grow. But also I think Rhodesia and Zimbabwe, with all their faults, have always been in some ways very open, because we’re a landlocked country, so we have to open ourselves up—although we’re also very conservative, actually—but we have to open ourselves up to other things, otherwise it becomes far too insulated and uncomfortable. I think we have always been aware that there’s a lot around you and that you’re borrowing. If you think about the migrations and the mines, we’ve had people moving across borders in the southern part of Africa for over a century. You can’t tell that story as one that’s not fluid. Even the fact that in the novel Genie’s great-grandfather comes to South Africa to get a job—that’s the way the world has been. It’s not: I was born here, I stayed here, I’m going to die here.

The JRB: The novel is rooted in real historical events, but at the same time feels somehow timeless. At one point you mention a group of people engrossed in their ‘portable electronic devices’, which I thought was a great way of saying ‘iPhone’. That phrase that seems to put a distance between the authorial voice and the real world. In fact the whole book has an aura of other-worldliness.

Siphiwe Gloria Ndlovu: I don’t like iPhones.

The JRB: Samsung? Android? You do use the word smartphone at one point but ‘portable electronic devices’ seemed very a deliberate word choice. To me it almost gave the impression it was an ancestor telling the story.

Siphiwe Gloria Ndlovu: That would be nice. I hadn’t thought of that. This is not a case of defamiliarisation, but I do like taking the things that we take for granted and are familiar with and just talking about them in a way that makes you think about what they actually are. I do have those moments.

The JRB: ‘Samsung’. Very unpoetic.

Siphiwe Gloria Ndlovu: It is it’s name, but yeah. It’s very difficult to say what you’re doing in the process of writing but I think that is how I tend to talk about things. And I’m not very technologically savvy, so.

The JRB: There’s a wonderful turn of phrase in the book, some of my favourites being how a model ‘looks into the distance as if it holds a future in which she is not particularly interested’, or, ‘our eyes are not for beauty to see’, which becomes a kind of refrain. I actually googled that to see if it came from somewhere, but it doesn’t.

Siphiwe Gloria Ndlovu: It’s beautiful because I think most of the time when you’re thinking of a story you’re thinking of the overarching story, this is what’s going to happen, and then when you start writing the words just come, and there are those phrases that make you go—whoa. That’s nice. But you’re not thinking about it beforehand. It’s sort of like a gift and you don’t know where it’s coming from. One of them was ‘our eyes are not for beauty to see’, because even I’m not sure what that means. But the characters kept on saying it, so I kept on writing it. I really like the way it sounded. Where that comes from, I don’t know. If I had to spend hours thinking about it, then that’s not writing anymore, it’s something else entirely. I think the thing is to be open enough to hear that for what it is. And trust your instincts.

I just finished the first draft of the second novel. The Theory of Flight took a long time, and with this one within six weeks the first draft was on paper, and that’s when you realise that it’s really not you. Once you start writing this whole world starts unfolding, and these people are the ones telling you the story, so you have to listen. In that moment you are a conduit. Saying ‘transcriber’ makes it seem very unromantic, but you’re just basically transmitting what you’re hearing on to paper, and you just have to be faithful to that person. So part of me doesn’t want to say ‘yes, I’m the one who carves out these wonderful words’, because it’s more complicated than that. I think stories choose you because they think you are capable of telling them. But then what the story becomes is something beyond you. Something that you yourself hadn’t fully imagined, and that’s the beauty of it.

The JRB: To turn to more a secular question, at one point, one of your characters describes another’s PhD dissertation as being about ‘the history of your country, how it was never able to become a nation because the state focused belonging too singularly on the land’. Do you have any thoughts on the current land debate?

Siphiwe Gloria Ndlovu: That’s me making fun of my own dissertation. [laughs] It’s such a complicated issue. I think the land and the way we attach ourselves to it devalues it in the process. I think belonging is a much more complicated thing. My own family, where our, what we call, ekhaya is, is not where it was originally. But then my family came from Swaziland, KwaZulu-Natal, Botswana, so what do we mean by ‘home’? Zimbabweans have been migrating for quite some time. When we focus our belonging just on the land, it limits the idea of who we are. In the seventies when we went to war, it was: these are the sons of the soil, fighting to get the land back. It limits our relationship to one another, and our relationship to the country, because our relationship to those two things happens through the land, and it’s detrimental. I think it doesn’t allow us to put the country first.

What’s missing a lot in Zimbabwe right now is doing things for the country. We usually talk about how rich the land is, how many minerals it has, how certain parts of it are very good for agriculture, which is great, but you’re just thinking about what that land can give you, you’re not thinking, ‘How can I take care of this?’ And you can tell by the rapacious way that the current government is just going at the mineral wealth that they don’t have a true understanding of and true love for the land. They land is just there to give them what they want. I think if we had a healthy relationship to the land, that’s not what we would do. You would say, ‘This is ours in perpetuity and our children are also supposed to benefit from this.’ I don’t know what’s going to happen in South Africa, but in Zimbabwe I think that was definitely not the way to think about who we were, because when you’re building a nation, you have to think about the things that connect you, and we never did that. Real nation-building is saying, we have all these differences, how do we make something that we can all share in together? And that just never happened. Zimbabweans will talk about how the country is so rich in minerals, but they don’t necessarily talk about themselves as being anything of value. They don’t say ‘The country has us.’ That’s already telling you that something is wrong.

The JRB: Your PhD work focused on Sarah Baartman: you begin by recalling how when you first encountered Baartman you saw her as the ideal woman, and then ask whether it’s viable to retain this way of seeing her, as opposed to seeing her as a marker of something negative. Did these ideas inform your creative writing, at all?

Siphiwe Gloria Ndlovu: Maybe tangentially. Most of what the essay you’re referring to was about was how there’s a narrative that keeps re-abusing her. In the nineties and early-two-thousands there was this need to recuperate her, and it seemed to me that we were very happy to do that, but how we were doing it was not sufficient, not treating her with the care she deserved. So the essay was about how we need to move away from the Western narrative itself, to try and imagine who she was, in her context. Because that’s the story. Who was she, did she see herself the way that we’ve been made to see her? Obviously not. Did she see herself as a sad thing? Probably not. Did she see herself as a totally violated and abused woman when she got to Europe? Probably. But maybe not for the reasons that we seem to assume were at play at that time. So we need to understand that we are also looking at her through this lens that is going to keep hurting her over and over again, and we need to move away from that.

I don’t know if it informed this book, but intellectually I’m always about—the Western narrative is great, but we should never just assume that we’re either in response to it, or that our story has to be part of it, or that we don’t have stories ourselves. That’s why when people say ‘magical realism’, I’m like, according to who? From where I’m standing that’s just how you tell a story. But if you’re looking through a Western lens of course it’s different. I’m always very aware that it’s important to say, we have stories too, we have lives too, we experience things, and that’s just as valuable and as viable as anyone else. I’m not going to say something about the way I look because some white man two hundred years ago said that it wasn’t beautiful. What do you think it was? What do you still think it is? We do that even now. There’s all this talk about women having certain kinds of bodies, and how that’s not attractive anymore. But if seventy-five per cent of the women look like that, then you’re making them feel bad about themselves for the way they look naturally? Where is that aesthetic coming from?

The JRB: You’ve just moved back to Zimbabwe, after twenty years. How does it feel to be back home? Are you feeling a different vibe?

Siphiwe Gloria Ndlovu: I’m not the best person to ask, because I really, really love Bulawayo, where I come from, and I really don’t know much about the rest of Zimbabwe. I’m very regional in my consumption of the country. If you asked me what happens in Harare on the regular basis, I wouldn’t know. [laugh] I think people tend to have this one story, which is doom and gloom, but show me a country that’s not going through something rough right now. That’s what I wanted to show in the book, is that horrible things have been happening all the time; it’s not like people have not been enjoying life.

The JRB: I understand your next book is a crime novel?

Siphiwe Gloria Ndlovu: That’s what it said online, but no. It’s literary fiction, but part of it is there’s an investigation into someone’s death. So there’s a bit of a mystery element. But it’s not a straight-up genre novel. It’s about him and what happens in his life that leads to the moment of his death.

The JRB: And I read online that it will be a trilogy?

Siphiwe Gloria Ndlovu: It’s not actually, there’s this second novel and then there’s two other novels.

The JRB: A trilogy in four parts.

Siphiwe Gloria Ndlovu: [laughs] And they’re all interconnected.

The JRB: So we’ll see characters returning? That must be nice for you, because you know them by now.

Siphiwe Gloria Ndlovu: I felt like I knew them, but then when I started writing it was a wonderful experience. The main character is very different from who I am as a person, he’s a white guy, who’s a bit of a racist and a bit of a misogynist, and then he dies. And I was like, oh, so you’re not a nice person. But then when I started telling the story he was a very complex human being. Once you get to that point he stops being a caricature. I realised, so this is what happened to you, how do I tell your story so everyone sees it that way? I think it was because I told the story from when he was a child, once you do that there’s no way you can just paint a monster. But it was a great lesson for me in understanding the interiority of a character and empathising.

- Jennifer Malec is the Editor. Follow her on Twitter.