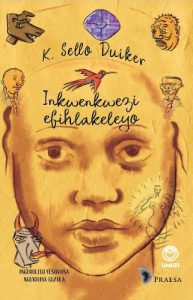

The JRB presents an excerpt from Inkwenkwezi efihlakeleyo, the new isiXhosa translation of the late K Sello Duiker’s modern South African classic The Hidden Star. Find the excerpt in its original English following the isiXhosa text.

The Hidden Star, Duiker’s third novel, was first published posthumously in 2006. This isiXhosa edition is translated by Xolisa Guzula.

Inkwenkwezi efihlakeleyo

K Sello Duiker (translated by Xolisa Guzula)

Penguin Random House South Africa, 2023

The following excerpt describes Nolitye going underwater to meet Noka, the Queen of the River, who tells her where Kwena has hidden her parents. Xolisa Guzula, who translated the book, says:

‘I have chosen this extract because this is one of the areas where folklore (both oral storytelling and riddles) is integrated into this contemporary writing. For anyone who has been immersed in African stories, this comes as a point of making text-to-text connections between written language and oral folklore.

‘For me, especially, this is where we can create a bridge from oral language to written language for children learning about written literacy. The value of this is in valuing what children already know from oral literature and using it as a foundation to teach written literature. It is also about showing what fantasy or fantastic texts look like in African languages.’

More information about the translation follows the excerpt.

Read the excerpt in isiXhosa:

~~~

UNolitye ukhulula izihlangu neekawusi zakhe azinike uMaglasana, othe yena nabanye abantwana bamlandela bekunye nemvubu.

‘Awukwazi ukusuka ungene nje,’ uBheki uyalumkisa. ‘Siza kuthini ukuba awubuyi?’

‘Uza kubuya,’ uMvu utsho.

UBheki uwola uNolitye, ampampathe ubhaka awuxwayileyo aze amsebezele athi: ‘Ukuba yonke into ayihambi kakuhle, uze usebenzise ilitye.’

UNolitye uxelela abanye ukuba bangaxhalabi kuba uza kubuya ngokukhawuleza. Uphefumla nzulu, elindele ukuba kuza kufuneka ewubambile umphefumlo emanzini. Ungena emanzini, aze ehle, ehle, ehle, de eme emazantsi esiziba. Wothuswa kukufumanisa ukuba uyakwazi ukuphefumla ngaphantsi kwamanzi. Edada endaweni enobumnyama, ufikelela emlonyeni womqolomba omkhulu okhanya ngokuqaqambileyo. Uyangena ngoloyiko. Wothuswa nakukufumanisa ukuba iimpahla zakhe zomile. Ujonga eluphahleni aze aqaphele iqela lamalulwane abambelele kumphezulu orhabaxa. Kwikona emnyama ubona kuvela ixhegokazi elibi nelizithe wambu ngelaphu nje kuphela lisiza kuye. UNolitye ufikelwa yingcinga yokuba ajike abaleke, kuba ingalo yasekunene nomlenze wakhe wasekhohlo weli xhegokazi azikho. Lingcileza kane lifike ecaleni kukaNolitye. Isikhumba seli xhegokazi sishwabene yaye sichachambile, kangangokuba siyaphuqeka ezingqinibeni nasemadolweni.

‘Ndiyazazi ukuba ndimbi kwaye ndimdala, mntwan’ am,’ utsho. ‘Nokuba ungahleka, sokuze ndikubeke tyala.’

‘Dumela, Mama,’ uNolitye uyaphendula. ‘Ndingakuhleka njani njengokuba intliziyo yam ilusizi ngawe?’

‘Ukuba into oyibonayo ayikonyanyisi, mntwan’ am, ngoko ke nceda undikhothe ezi zilonda zam ngolwimi lwakho olunyangayo,’ utsho lo makhulu.

UNolitye akathingazi aze enze njengoko eyalelwa. Ixhegokazi liqalisa ukungcangcazela nokushukuma. Emangaziwe, uNolitye uyabukela ngelixa ixhegokazi litshintsha. Liqala ngokukhula ingalo, kulandele umlenze. Ubuso bakhe buqalisa ukukhangeleka butsha kwaye bubebuhle, neempahla ziqalise ukuligquma. Uma phambi kukaNolitye, ombethe ingubo yabeSotho eneepateni ezintle egxalabeni lakhe lasekhohlo, entloko ethwele umnqwazi omile okwekhowuni owolukwe ngengca. Intamo yakhe nezihlahla zakhe zihonjiswe ngamaso anxitywa ngamakhosazana kuphela. Uphethe umsimelelo onentloko yendlovu oqingqwe ngobuchule esiphelweni sawo—umqondiso wobukhosi.

‘NdinguNoka,’ uyazazisa, ‘Ukumkanikazi weMimoya yoMlambo, kwaye ndizibonakalisa kuphela kubantu abafanelekileyo. Unentliziyo entle, mntwan’ am, kwaye uluphumelele uvavanyo. Ndingakuvuza ngantoni?’

‘Igama lam ndinguNolitye, Mama, kwaye ndikhangela abazali bam. UNcitjana wababamba wabavalela kubuhlanti bakhe, kodwa abasekho phaya. Kuthiwa, uNcitjana wanikezela ngomama wam kwiMimoya yoMlambo ukuze afumane amandla ongezelelweyo, kwaye mna ndizama ukubafumana,’ uNolitye uyachaza. ‘Ungandinceda?’

‘Ndayiva into eyenziwe nguNcitjana, mntwan’ am. Wajika uyihlo wamenza umthi webaobab okhula kufutshane namangcwaba eendlovu, waze wanikezela ngonyoko kuKwena, ingwenya, ukuze abenamandla okulawula iZim. UKwena ufihlile unyoko ndaweni ithile kwezi ngxondorha ziphantsi kwamanzi. Kodwa andazi ncam ukuba ndawoni. Kuza kufuneka umlinde mntwan’ am. Eyona ndlela yokuba ubone unyoko kwakhona kukucela umngeni uKwena. Ukuze ufumane uyihlo ke, kuza kufuneka uye kumangcwaba eendlovu.’ UNoka uyayeka ukuthetha, ajike intloko yakhe ukuze amamele, aze athi, ‘UKwena sele ezakubuya.’

Uthi egqiba ukuwatsho nje la magama suka kuthi gqi ingwenya eyoyikekayo ibhukuleka iziveza. UNolitye utsala umoya ngokukhawuleza xa ebona indlela amkhulu ngayo uKwena. Amazinyo akhe akhule aphumela ngaphandle aze agcwala ubulembu, kwaye uyagquma ngelixa ebuthuma, umzimba wakhe ungamanga kakuhle. Amaxolo akhe asabumdaka ngebala ayashukuma yaye ugqunywe ngudekede. Imilenze yakhe mifutshane, yaye ityebile, kwaye uneenzipho ezinde ezigobileyo.

‘Mhmmm, inyama yomntu emnandi endilindileyo,’ utsho uKwena, evula amabamba akhe oyikekayo.

‘Lo mntwana uzokulanda unina,’ uNoka uyangenelela. ‘Lo mfazi umfihle apha. Ndandikulumkisile ukuba le mini iyakuze ifike.

‘Akukho mntu uza kumfumana! Ndenza isibhambathiso noNcitjana.’ Aze uKwena abethekise umsila wakhe osindayo kumgangatho onesanti.

‘Kwena, uyawazi umthetho,’ uNoka utsho ngqongqo.

‘Ewe, ewe, akunyanzelekanga ukuba undikhumbuze.’

‘Wuphi wona umthetho?’ uNolitye usebezela uKumkanikazi woMlambo.

UNoka uyachaza: ‘Eyona ndlela yokuhlangula nabani na kwilizwe lemiMoya yoMlambo kukuphendula iqashiso.’

‘Kodwa ukuba lo mntwana umncinci akaliphenduli ngokuchanekileyo iqashiso, naye kuzakufuneka ahlale apha.’ UKwena ungqavula amazinyo akhe ukubonisa ugxininiso lwakhe lwesilumkiso.

UNolitye uyabhekabheka, ecinga ngendlela emoyikisa ngayo into yokuba kungenzeka avaleleke apho naphakade. Kufuneka aphendule iqashiso ngokuchanekileyo! Kufuneka abafumane ze ababuyise abazali bakhe! ‘Lithini iqashiso?’ uyabuza.

UKwena uyasondela, erhuqa umzimba wakhe kumgangatho onomhlaba. Umphefumlo wakhe unuka kakubi kwaye ubukho bakhe nje emqolombeni budala uloyiko. ‘Qaqhi-qashi ndinanto yam ikho kwindawo yonke esingqongileyo kwaye iyazifihla kwikona nganye, nakwiindawo ezibuncinci obulungana ne-ertyisi …’ Iingqanda zamehlo kaKwena ziyakhula zibe nkulu ngelixa ejonge kuNolitye, ezama ukumvavanya. ‘Itshatyalaliswa yinto enye kuphela, ukukhanya. Yintoni?’

‘Yicingisise ngononophelo, mntwan’ am. Okanye nawe uyakuvaleleka apha unaphakade,’ utsho uNoka.

UNolitye uziqhekeza intloko ezama ukufumanisa impendulo echanekileyo yeqashiso. Ucinga ngelulwane, kodwa ilulwane alikwazi kuzifihla kwi-ertyisi. Ujonga kuNoka, ezama ukumcenga ngamehlo akhe, kodwa uyazi ukuba uKumkanikazi woMlambo akanakumnceda. Akakwazi nokubuza ilitye elingcwalisekileyo, kuba uKwena uza kumbona xa elikhupha kubhaka ilitye.

‘Ndilindile!’

‘Mnike ixesha, Kwena!’ uNoka uyamyalela.

UNolitye uzixelela ukuba kufuneka ethobe umoya. Uyacimela ukuze acinge ngcono. Ucinga ngonina wokwenene ohleli yedwa ebumnyameni ndaweni ithile. Uvakalelwa ngokufudumeleyo luthando aze ayibone impendulo ngokucacileyo. ‘Ndiyifumene!’ uyakhwaza.

‘Ke ngoku?’ uKwena usondelela kufutshane.

‘Eyona nto enokutshabalalisa ubumnyama kukukhanya. Kwaye ubumnyama bungazifihla endaweni encinci ngokulingana ne-ertyisi.’

‘Wenze kakuhle, mntwan’ am,’ uKumkanikazi woMlambo utsho. ‘Ndiyazile ukuba uza kuyichana.’

‘Ukopile! Ukopile!’ uKwena utsho ngomsindo. Ungqavula amazinyo akhe aze abethekise phantsi umsila wakhe.

‘Kwena, uyayazi into yokuba khange akope. Ebelapha. Khulula unina phambi kokuba ndikugxothe unaphakade kulo mlambo.’

‘Kulungile!’ uKwena utsho equmbile. Amehlo akhe ayancineka njengoko ezirhuqa nzima ukuya ngasemva komqolomba aze aqalise ukomba. UNolitye noNoka bambukela ekhaba isanti nomhlaba ngemilenze yakhe eyomeleleyo. Uyacotha kodwa ngenzame nganye ayenzayo ususa inqumba yomhlaba. Emva kwethuba, kuvela iqanda elikhulu elimthubi. UNolitye uthatha amanyathelo asondele azokujonga. UKwena wemba ngocoselelo emacaleni eqanda, ngelixa embombozela esithi uNolitye ukopile.

‘Nanku unyoko,’ uyambombozela, eqengqa iqanda elikhulu ngononophelo elizisa ngakuye. UNolitye akazi ukuba makathini. Akazazi ukuba uziva kanjani; uchulumancile kodwa uyoyika. Aze afikelwe ziinkumbulo: wayelibonile iqanda elifana neli, kodwa lilincinci kuneli—kunye nomthi webaobab!—ekhukhanyeni kwelitye lomlingo ngala mini yena noBheki babethengisa amagwinya kwisitishi setreyini saseMogale. Zange aqonde ukuba ilitye lalimnika umqondiso ngento eyenzeke kubazali bakhe. UNolitye ujonga kuNoka, intliziyo yakhe ingongoza ngamandla.

‘Kwena, mncedise alivule,’ uKumkanikazi woMlambo uyalela isirhubuluzi esikhulu.

Ingwenya equmbileyo, iqhekeza iqokobhe leqanda ngocoselelo ngamazinyo ayo amakhulu iqalise ukuliqhekeza nangona ikwenza oku ingathandi. Kuqala, uNolitye noNoka babona iinyawo ezimbini, baze xa uKwena elixobula kakhulu iqokobhe, babone iingalo, imilenze kunye nentamo; umama kaNolitye ulele ezisongile oku kanye kosana olungekazalwa. Lithi lakuba liqhekezwe lonke iqanda, uKwena akrwece uThembi ngemhemfu yakhe ende. Uyaqalisa ukushukuma, ezidlikidla kancinci. Aze aphulule ubuso bakhe, azamle ngathi ebekobude ubuthongo. UNolitye akakwazi kuma bhunxe luchulumanco. UThembi uphakama ngokucothayo aze azolule. Kukho udekeda kancinci ebusweni bakhe.

UNolitye ufikelwa ziimvakalelo ezininzi. Wonwabe kakhulu kangangokuba ufuna ukulila, kodwa uyazibamba iinyembezi. Uyalithanda aze alimamelisise eli thuba lokubona unina wokwenyani emi phambi kwakhe. Ngoku uThembi umile kwaye wolula ilokhwe yakhe, ilokhwe yelaphu elimdaka ngombala. UNolitye akakholelwa ukuba ithuba ekukudala elilindele lifikile. Amatyeli aliwaka ebesoloko ezenzela umfanekiso ngqondweni wokuba aungaziva njani na xa embona unina wokwenyani kwakhona, kwaye ngoku ami phambi kwakhe, akayikholelwa indlela anexhala ngayo. Nendlela aneentloni ngayo. Indlela aziva ngayo ifana nqwa nokudibana nomntu ongamqhelanga.

‘Yiya kuye,’ uNoka u sebezela uNolitye.

UNolitye uthatha inyathelo eliya phambili, isisu sakhe sixuxuzela.

UThembi ukhangeleka ediniwe yaye edidekile. Uyaqhwanyaza ekukhanyeni komqolomba. Kumthatha ixesha ukukuqhela ukukhanya. UKwena uyakhalaza.

‘Ndiphi?’ uThembi utsho ngelizwi eliphantsi, ejonge kuNoka nakunoNolitye ukufumana impendulo. Abathethi. UThembi uza kubo aze athi xa ephakama, kubekho umothuko ebusweni bakhe.

‘Ayikwazi kwenzeka le nto,’ utsho, esondelela kufutshane.

UNolitye uma apho engcangcazela; akazi nokuba makenze ntoni.

‘Nolitye nguwe lo?’ uThembi uyabuza, emjonge ntsho. Uyambombozela aze awe phantsi emadolweni akhe xa eqonda ukuba ujonge intombazanana yakhe ekukudala yamlahlekela. UNolitye ubaleka aye kunina aze aphose iingalo zakhe kuye. Bobabini baqalisa ukulila, bekhala iinyembezi zovuyo. Unamehlo anothando nto leyo emqinisekisayo uNolitye ukuba ngenene lo ngunina wokwenyani. Zonke iinkxwaleko abadibene nazo zikhangeleka zingenamsebenzi ngoku; aze ancamathele kuThembi, ebulibala bonke ubunzima.

‘Noli, bendicinga ukuba andisokuze ndiphinde ndikubone,’ utsho uThembi, embambe emqinisile.

UKumkanikazi weMimoya yoMlambo ubasikelela ngoncumo ngelixa uKwena ebhukuleka esimka efutha.

‘Mama, kufuneka sihlangule uPapa,’ uNolitye uyakhumbula. ‘Ukumangcwaba eendlovu. UNcitjana umjike wangumthi webaobab.’

~~~

Read the excerpt in English:

Nolitye tells the others not to worry because she will soon be back. She takes a deep breath, expecting to have to hold it. She submerges herself, sinking down, down, down, until she stands on the bottom of the pool. To her amazement she can breathe underwater. Groping in the half-darkness she ends up at the mouth of a large, brightly-lit cave. She enters timidly. To her surprise she finds that her clothes are dry. She glances up at the roof and notices bunches of bats clinging to the rough surface. From a dark corner at the back an ugly old woman, wearing just a simple loincloth, emerges. In large hops the woman bounds towards her. Nolitye is tempted to turn her head away, because the woman’s right arm and left leg are missing. In four hops she is at Nolitye’s side. The old woman’s skin is wrinkled and cracked, peeling at the elbows and knees.

‘I know I am ugly and old, my child,’ she says. ‘You may laugh, I will not blame you.’

‘Dumela, Mama,’ Nolitye answers. ‘How can I laugh when my heart goes out to you?’

‘If the sight of me doesn’t put you off, my child, then let the balm of your kind healing tongue heal me by licking my wounds,’ the old woman says.

Nolitye doesn’t hesitate and does as she asks. The old woman starts shivering and shaking. Fascinated, Nolitye watches as she changes. First she grows an arm, and then a leg. Her face takes on a youthful beauty and clothes start covering her body. She stands before Nolitye, an elaborately patterned woollen Basotho blanket draped elegantly over her left shoulder, her head covered by a conically shaped hat of woven grass. Her neck and wrists are decorated with beads only queens wear. She holds a staff with an intricately carved elephant’s head at one end—the sign of royalty.

‘I am Noka,’ she introduces herself, ‘Queen of the River Spirits, and I show myself only to deserving souls. You have a compassionate heart, my child, and have passed the test. How can I reward you?’

‘My name is Nolitye, Mama, and I’m looking for my parents. Ncitjana imprisoned them in his kraal, but they are no longer there. You see, Ncitjana offered my mother to the River Spirits to get more power, and I am trying to get her back,’ Nolitye explains. ‘Can you help me?’

‘I have heard of what Ncitjana did, my child. He turned your father into a baobab tree that grows near the elephant graveyard, and offered your mother to Kwena, the crocodile, to have power over the Zim. Kwena has hidden her somewhere in these underwater caverns. But I don’t know where. You will have to wait for him, my child. The only way you will ever see your mother again is if you are willing to confront Kwena. To find your father, you will have to go to the elephant graveyard.’ Noka stops talking, turning her head in order to listen, and says, ‘Kwena is about to return.’

No sooner has she uttered the words than a hideous crocodile waddles into sight. Nolitye pulls in her breath sharply when she sees how big Kwena is. His teeth are overgrown with moss and he heaves as he crouches, his body misshapen and ungainly. His brownish scales are loose, covered in slime. His legs are short and stubby, with long curved nails.

‘What delicious human flesh awaits me,’ Kwena says, opening his dreadful jowls.

‘The child has come to get her mother,’ Noka intervenes. ‘The woman you keep hidden here. I warned you this day would arrive.

‘No one will have her! I made my deal with Ncitjana.’ And Kwena slams his heavy tail on the sand floor.

‘Kwena, you know the law,’ Noka says sternly.

‘Yes, yes, you don’t have to remind me.’

‘What law?’ Nolitye whispers to the Queen of the River.

Noka explains: ‘The only way to rescue anyone from the River Spirit world is by answering a riddle.’

‘But if the young one doesn’t answer the riddle correctly she too will have to stay here.’ Kwena snaps his jaws shut to underline his threat.

Nolitye looks about her, considering the frightening prospect of being trapped here forever. She must answer the riddle correctly! She must get her parents back! ‘What is the riddle?’ she asks.

Kwena moves closer, dragging his body along the sandy floor. His breath smells foul and his presence fills the cave with gloom. ‘It is everywhere around you and hides itself in every corner, even in places the size of a pea … ’ The pupils of Kwena’s reptilian eyes grow bigger as he looks at Nolitye, sizing her up. ‘It is only destroyed by one thing and that is light. What is it?’

‘Think about it carefully, my child. Or you will be stuck here forever,’ Noka says.

Nolitye wracks her brains trying to figure out the riddle. She thinks of a bat, but a bat can’t hide in a pea. She looks at Noka, pleading with her eyes, but she knows that the Queen of the River dare not help her. And she can’t ask the sacred stone, because Kwena would see if she took it out of her bag.

‘I’m waiting!’

‘Give her time, Kwena!’ Noka orders him.

Nolitye tells herself to calm down. She closes her eyes so she can think better. She thinks about her real mother alone in the dark somewhere. A warm feeling of love comes over her as she sees the answer clearly. ‘I’ve got it!’ she shouts.

‘Well?’ Kwena edges closer.

‘The only thing that can destroy darkness is light. And darkness can hide itself in a place as small as a pea.’

‘Well done, my child,’ the Queen of the River says. ‘I knew you could figure it out.’

‘She cheated! She cheated!’ Kwena says angrily. He snaps his jaws and thrashes his tail about.

‘Kwena, you know she didn’t cheat. I was right here. Release her mother before I banish you from this river.’

‘Alright!’ Kwena sulks. His eyes become mere slits as he sluggishly drags himself to the back of the cave and starts digging. Nolitye and Noka watch him kicking back the sand and soil with his powerful hind legs. He is slow but with every stroke he moves a whole heap of earth. After a while a large, pale-yellow egg appears. Nolitye steps closer to take a look. Kwena carefully digs around the egg, all the while grumbling that Nolitye cheated.

‘Here’s your mother,’ he mutters, cautiously rolling the huge egg towards her. Nolitye goes blank. She doesn’t know what she feels; she’s excited but scared. And then a memory comes to her: she saw this same egg, just smaller—and a baobab tree!—in a flash of light from the magic stone the day she and Bheki sold fatcakes at Mogale station. She didn’t realise then that the stone was giving her a hint as to what had happened to her parents. With a thumping heart, Nolitye looks at Noka.

‘Kwena, help her open it,’ the Queen of the River orders the enormous reptile.

The grumpy crocodile reluctantly, but with great care, cracks the shell of the egg with his huge teeth and starts breaking it open. First Nolitye and Noka see a pair of feet, then as Kwena peels away more shell they see arms, legs and a neck; Nolitye’s mother sleeps curled up like an unborn baby. When the egg has been broken open completely, Kwena pokes at Thembi with his long snout. She starts moving, wriggling a bit. Then she rubs her face and yawns as though she has been in a deep sleep. Nolitye can’t stand still with excitement. Thembi gets up slowly and stretches. There is a bit of slime on her face.

A flurry of emotion goes through Nolitye. She’s so happy that she wants to cry, but she swallows back the tears. She savours the moment of seeing her real mother before her eyes. Now Thembi is standing up and straightening her dress, a plain mud-coloured cotton dress. Nolitye can’t believe this moment has arrived. A thousand times she has imagined how she would feel when she saw her true mother again, and now that she is standing in front of her she can’t believe how nervous she is. How shy she feels. It is like meeting a stranger.

‘Go to her,’ Noka whispers to Nolitye.

Nolitye takes a step forward, her stomach doing somersaults.

Thembi looks groggy and confused. She blinks her eyes against the light in the cave. It takes a while before she gets used to it. Kwena moans to himself.

‘Where am I?’ Thembi says softly, looking at Noka and Nolitye for an answer. They say nothing. Thembi walks towards them and then she stops, a look of shock on her face.

‘It can’t be,’ she says, stepping closer.

Nolitye stands there trembling; she doesn’t know what to do.

‘Nolitye is that you?’ Thembi asks, looking intently at her. She utters a low moan and falls to her knees when she realises that she’s looking at her lost daughter. Nolitye runs to her mother and flings her arms around her. They both start weeping with joy. Thembi strokes Nolitye’s dreadlocks. There is a gentleness in her eyes that affirms to Nolitye that this is her real mother. All the ordeals that she’s been through no longer seem to matter; she clings to Thembi, forgetting every hardship.

‘Noli, I thought I’d never see you again,’ Thembi says, holding her tightly.

The Queen of the River blesses them with a benign smile while Kwena waddles out in a huff.

‘Mama, we have to save Papa,’ Nolitye remembers. ‘He is at the elephant graveyard. Ncitjana turned him into a baobab tree.’

~~~

- At the time of his untimely death in January 2005, K Sello Duiker had published various short stories and two novels: Thirteen Cents, which was awarded the Commonwealth Prize for a first novel (Africa Region), and The Quiet Violence of Dreams, which won the Herman Charles Bosman Prize for English Literature. For many aspiring South African writers, he served as a role model, someone who fearlessly tackled unconventional themes and explored new terrain. For an older generation of writers his work epitomised the best of post-1994 South African black writing. He spent a large part of his childhood in Soweto, where he was born on 13 April 1974. Further education followed in England when his father took up a position with an international company. After obtaining a degree in journalism at Rhodes University, he worked as a copywriter in advertising and as a scriptwriter for the television soap operas Backstage and Isidingo.

- Dr Xolisa Guzula is a Senior Lecturer in Applied Language and Literacy Studies, with a focus on multilingual and multiliteracies education, at the University of Cape Town. She specialises in multilingual education, especially in teaching children to speak, read and write in two or more languages. She is one of the founders of a network of reading clubs growing across the country starting from the Vulindlela Reading Clubs to Nal’ibali Reading Clubs and the Stars of Today Literacy Club. She has written several children’s books, including the recent series of Imbokodo: Women Who Shape Us, and has translated a number of children’s books from English to isiXhosa, including books by award-winning authors such as Astrid Lindgren’s Brothers Lionheart, as well as books by Niky Daly, Sihle-isipho Nontshokweni, Refiloe Moahloli and Nicholas Maritz. She won an IBBY/Exclusive Books award for best translation of The Elders at the Door by Shale and Maryanne Bester to Iinkonde eMnyango. Her translation of Wendy Hardie’s book The Singing Stone/Ilitye Eliculayo made the honour list of IBBY 100 recommended books across the world. Xolisa is a member of Bua-lit Language and Literacy Collective, working on social justice in language and literacy education. She is also the Vice Chair of the Western Cape Committee of the Literacy Association of South Africa.

~~~

Publisher information

For the first time, K Sello Duiker’s well-known The Hidden Star is now available in isiXhosa.

Dr Xolisa Guzula, who translated the book, describes it as a form of repatriation. ‘Writing in English is both a choice and at most times the only option for black authors because of the poor publishing of writing in African languages.’ For Guzula, this means bringing back what should have been written in African languages in the first place.

She credits the idea of translating the book to Carole Bloch and Arabella Koopman, both from the Project for the Study of Alternative Education in South Africa, PRAESA. As part of the Culture of Reading Project, books were created for isiXhosa readers via translation since publishers were still hesitant about publishing original literature. Added to that, original writing in isiXhosa children’s literature was still in its infancy and there was a shortage of isiXhosa reading books. While the translation of The Hidden Star is the continuation of that work, it also switches focus to translating a black South African author writing in English, after years of translating white authors writing in English.

‘I see this not only as a transformative project but also the development we have been wishing to see; the growth of South African black authors writing for children in any language,’ Guzula says.

Duiker’s use of myth really excites Guzula: ‘The folklore that Duiker weaves into the book is an example of bringing African stories to the contemporary novel, one detailing urban life in a shanty town in Soweto. As a translator, it was easy for me to predict what was going to happen next in certain parts of the book because I could recognise the rich folklore of African stories told to me as a child.’

Inkwenkwezi efihlakeleyo is published by Penguin Random House South Africa.

Delighted to find this!