The JRB presents an extract from ‘Biography’, excerpted from Human Sacrifices, the new short story collection by acclaimed Latin American writer María Fernanda Ampuero.

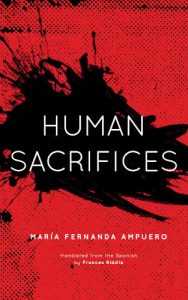

Human Sacrifices

María Fernanda Ampuero (trans. Frances Riddle)

The Feminist Press, 2023

Read the excerpt:

Biography

What a fool, she’s insane, you might say, but I want you to see me living undocumented in a foreign country carefully counting the few bills I have left to pay my rent and buy a loaf of bread and a cup of black coffee. Desperation and the internet collide, mount each other, engender monstrous beasts, aberrations.

I go online to the Seeking Employment pages and post all the kinds of jobs that they might give someone like me. Cleaning, caretaking, washing, sewing, selling, handing out, filing, picking up, stacking, restocking, growing, greeting, watching. They call and immediately ask about my papers.

‘I’m in the process of getting my residency.’

‘Call us when you have it.’

Or:

‘Papers in order?’

‘Not yet.’

‘We don’t hire illegals.’

Over and over, every day.

Anxiety creeps up my neck like a cold, crinkly black insect with a stinger. Do you know the creature I’m talking about? It’s hard to explain the feeling when it nests on your back. It’s like dying but you’re still alive. Like trying to breathe underwater. Like being cursed.

Under these circumstances, writing is the most useless thing in the world. It’s a ridiculous skill, a dead weight, a kind of hubris. I’m a foreign scribe documenting a world that despises her.

One day after countless ads offering my services as caretaker, nanny, maid, cook and hearing, ‘Not without papers, we don’t hire illegals,’ I decide to post something absurd.

Do you think that your life story is worthy of a book, but you don’t know how to tell it? Call me! I’ll tell your tale!

I didn’t think the message, with its exclamation marks, would interest anyone.

An hour later my phone rang. Unknown number.

‘I have a story that the world has to hear.’

The guy was named Alberto. He said that he lived in a small town in the north, that he could pay whatever I was asking, that he couldn’t give me more details over the phone, and that I’d have to go meet him the next day if I was interested in the job.

After a long silence, I asked for a lot of money because his voice frightened me, because I’d have to travel clear across a country that was not my own, and because I thought he would refuse to pay that amount to a stranger, not to mention a foreign stranger.

‘I’ll wire half the payment right now.’

His tone was overfamiliar, which scared me. That friendliness older men sometimes extend and you don’t know if it’s because they see you as a dumb daughter, because they want to get their hands on you, or both.

When I first emigrated here, my boss at the internet café, the one who told me I reminded him of his little girl back home, tried to rape me inside one of the phone booths where other people like me cried over their dead or consoled their living. When I resisted, he bashed my head into the telephone. With my mouth full of blood, I turned around, screamed, and spit in his face.

I ran half-naked out into the recently washed street and no one called the police because in that neighbourhood everyone knew that the police punished only undocumented people, not rapists.

My boss had his papers in order, so I’d be the one in trouble.

See me, see me. I run down the street wearing one shoe, my blouse torn open, my bra strap broken, skirt bunched up around my hips.

See me, see me. Shouting like I’ve just escaped an explosion, flames still blazing in my hair, the stench of scorched flesh, my teeth stained with black blood. I scream that I’m dying, that he’s trying to kill me.

See my neighbours, silent, on the sides of the street. Watching the procession of Our Lady of the Foreign Women, a saint who receives no offerings, whom no one gives a shit about.

I cried in the shower as my blood tinged the water red like in the movies, and the next day I started to look for a new job. I didn’t get paid for the days I’d worked at the internet café.

When this Alberto guy sent me the advance, a fortune, I had the urge to jump for joy, but something told me not to.

We undocumented immigrants have to hold our brightly coloured bills close to our chests, warming them against our hearts, treating them as if they were our children. We give birth to them with a wrenching pain the body doesn’t soon forget.

I thought about my options until my head hurt. I asked the woman who rented me a place to sleep in her living room, my only acquaintance in the city, my compatriot, and she told me that yes, it was dangerous, very dangerous in fact, but sleeping on the street would be worse.

‘Look, honey, when you emigrate you know you’re in for the worst, like going off to war. You don’t emigrate if you’re going to be scared of every little thing. Grit your teeth and clench your thighs shut and do what you have to do: you know it’s already the first of the month.’

That day, with the money Alberto sent me, I felt human for a few hours. I wired money home, I called my parents and told them to kiss my daughter for me, I went into a supermarket and bought meat and fresh fruit, I had coffee with milk on a café terrace like any normal woman.

Then fear sprayed me with its acid water. I scarfed down my dinner like a stray dog. I caught an overnight bus headed north. Somewhere along the way, I don’t know what time, I fell asleep.

I dreamed that a turkey had gotten into my daughter’s room and was pecking at the soft spot on her head. I immediately understood that the turkey was a demon and that demons feed on the pure thoughts of infants. I wanted to scream, but I didn’t have a mouth. The screams echoed through my brain, everything inside shaking like a maraca, making my heart swell until I couldn’t breathe. I didn’t have legs. I didn’t have arms to pick up my baby and take her away from the turkey. I wasn’t a person, I was an eye—an eye that cried the bloody milk of an infected nipple onto my daughter. The turkey turned around, looked at me. Its face was my face. It screamed: Run.

‘Run!’

I was woken up by my own screams, and the woman sitting beside me gave me a dirty look and changed seats. Stupid foreigner, she thought. They’re so strange, she thought. I bet she’s sick, she thought. I disgusted her.

Waiting for me at the station was a man who wasn’t Alberto but who, he said, was a ‘disciple of Master Alberto.’ He was old or looked it: toothless and so stooped that I was a full head taller. He wore a black shirt and pants and a kind of velvet cape with a hood that seemed out of place among all the people in puffer coats.

I considered saying I had to go to the bathroom, then buying a return ticket and putting the whole thing behind me, but I stayed because I wanted the other half of the payment. What had I come here for if not to make money? What had I come here for if not to try my luck? What had I come here for if not to survive no matter what?

Desperate women serve as meat for the grinder. Immigrant women are bones to be pulverised into animal fodder.

Unhardened bone. Pure cartilage. The soft spot on the head of the world.

~~~

- María Fernanda Ampuero is a writer and journalist born in Guayaquil, Ecuador, in 1976. She has been published in newspapers and magazines around the world and is the author of two narrative nonfiction titles and two short story collections: Cockfight and Human Sacrifices. In 2012 she was selected as one of the 100 Most Influential Latin Americans in Spain.

~~~

Publisher information

This acclaimed short story collection by a groundbreaking voice in contemporary Latin American literature confronts machismo, inequity, and violence.

An undocumented woman answers a job posting only to find herself held hostage, a group of outcasts obsess over boys drowned while surfing, and an unhappy couple finds themselves trapped in a terrifying maze. With scalpel-like precision, Ampuero considers the price paid by those on the margins so that the elite might lounge comfortably, considering themselves safe in their homes.

Simultaneously terrifying and exquisite, Human Sacrifices is ‘tropical gothic’ at its finest—decay and oppression underlie our humid and hostile world, where working-class women and children are consistently the weakest links in a capitalist economy. Against this backdrop of corrosion and rot, these twelve stories contemplate the nature of exploitation and abuse, illuminating the realities of those society consumes for its own pitiless ends.