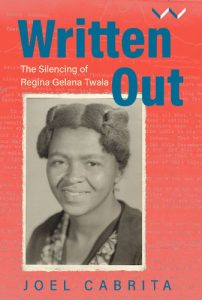

The JRB presents an excerpt from Joel Cabrita’s new book Written Out: The Silencing of Regina Gelana Twala.

Written Out: The Silencing of Regina Gelana Twala

Joel Cabrita

Wits University Press, 2023

Read the excerpt:

Wits

I am beginning to adjust myself gradually, icuriosity kubelungu iningi kabi [the whites’ curiosity about me is really terrible]

—Regina to Dan, February 11, 1943 (RTP)

Lecturers asked Black medical students at the University of the Witwatersrand to leave the room when European cadavers were cut open and splayed out for observation. They were also asked not to wear their white medical coats as they entered and left Johannesburg Hospital. This was so European patients could remain unaware that African doctors-in-training were in the building. White lecturers and professors also commonly asked their Black students to sit at the very back of lecture theatres. And when Black students used the university’s library, the authorities expected them to sit in a separate ‘Non-European Reading Room’. Swimming pools, sports grounds, and university dances were all barred to Black students. Regina may well have continued playing tennis, but regulations would have forced her to walk to a single ‘non-European’ court at the far end of the campus. Such were the realities of being a Black student at Wits in the nineteen-forties.

South Africa’s entry into World War II marked a watershed in the history of the university. This was the start of the so-called open years, a period during which the university admitted Africans into the medical school for the first time, and the number of African students in other schools also grew. This change was partly due to the fact that Black medical students had previously trained overseas—something that was now impossible due to wartime restrictions. And partly the newly permissive attitude toward admissions lay in the obviously desperate need for more doctors and social workers in Black urban communities as cities like Johannesburg grew exponentially during the war years. By 1945 there were 156 ‘non-white’ students (a designation that included African, ‘coloured’ [i.e., mixed-race], and Indian-descended students) out of a student body of three thousand.

But while in theory admission may have been possible for Black students (although not equal treatment at the university once they arrived there), the prohibitive cost of a degree meant many could not dream of entering. For Regina’s degree in social studies, tuition was probably about £50 a year, around three times the cost of her social welfare diploma from the Jan H Hofmeyr School. Her degree would take four years—years during which she would not be earning or contributing to the household’s finances. And money was still very tight for them. Despite Dan’s elevated status, he still struggled each month to reconcile his accounts—a common predicament for Black professionals in Johannesburg of the nineteen-forties. Throughout the years that he supported Regina at both the Hofmeyr School and at Wits, Dan repeatedly asked the sports club’s trustees for raises ‘in order to keep up the dignity of my position as Manager of the Club’. Their financial situation was further complicated by ongoing medical expenses for them both. Regina continued to see an army of doctors throughout for help with conception. And on Dan’s part, a devastating (and highly common) diagnosis of TB in 1942 meant new costs in connection with that: ‘The question of my health at this time when there is no £-s-d is a big problem … I only pray it may end quick, now that it has been discovered.’

Regina’s prospects for further education were saved only by the announcement in October 1942 by the Johannesburg branch of the all-white South African Association of University Women that it would be offering a ‘bursary for a degree course at the University of the Witwatersrand for a non-European woman’. However, the association required a matriculation certificate on the part of the successful applicant, something Regina didn’t have. Here, Dan and her connections to the white philanthropic world who financed these kinds of opportunities was crucial. An introduction to Wits’s influential Professor RF Alfred Hoernle—a philosopher as well as the then president of the Institute of Race Relations—seems to have secured her the scholarship. Regina proudly wrote to Dan after a meeting with university officials, ‘They say I can’t waste such brains, I must be helped to further my education. There is your wife, Twala.’

But despite the scholarship, financial worries never really receded for all Regina’s years at the university. It was only partial: amounts awarded ranged from £20 to £50 per year, meaning she and Dan still had to supply a significant sum. At least once, Regina was on the brink of being barred from attendance for late payment of fees. Such pressures were the norm among African students. The most famous example was that of Nelson Mandela, then a law student and who overlapped with Regina for nearly all her years at the university. Mandela’s studies nearly bankrupted him. He had to sell his house in Orlando—very near the Twalas’ home—as well as take out large loans. All this left Mandela ‘destitute and stranded’. Similar problems weighed on the Twalas. After several years of scrambling for fees, Regina wrote to Dan, ‘I am almost mad in the head to think about the hardships my man faces in funding my studies.’

In addition to fees, accommodations were the Twalas’ other practical worry about the degree course. Most Wits students were not residential, as the university had only limited accommodations on-site. The majority of (white) students lodged in boarding houses in the conveniently located surrounding white suburbs. Wealthier students opted for the large family homes of treelined Parktown while poorer, largely Afrikaner students lodged in the working-class area of Braamfontein, in which the university was itself located. But urban segregation laws meant neither of these options were open for Black students. They had to live much farther afield in areas like Sophiatown or even Orlando. Travel was expensive and lengthy, and various permits had to be obtained to legally move between downtown Johannesburg and Black residential suburbs at night. And even when they had the necessary documentation, conductors and drivers frequently treated Black students badly on public transport. Again, Mandela’s autobiography is illuminating. He describes being thrown off a ‘white tram’ by its driver and frequently spending the night in a jail cell while traveling back home from the university after late evening classes in the nineteen-forties.

Regina and Dan fretted over this problem at some length. Where was she to stay? They both worried that Orlando required too long a daily commute and would eat into Regina’s precious studying time. White liberals rallied once more—although in a typically ambiguous way. Ernst Jokl was a German Jewish refugee to South Africa. Jokl—a pioneering scholar of sports science—was introducing physical education to South African school curricula, including to Black schools. In connection with this, he worked closely with Dan at the sports club. Jokl and his wife, Erica, suggested a plan whereby Regina would stay in their centrally located house near the university and in exchange do housework in the afternoons and evenings after her classes were over. (The municipality offered exemptions for Africans spending the night in white areas if they were living on the premises as domestic workers.) This is Regina’s matter-of-fact account to Dan of what even Jokl recognised as a ‘humiliating’ offer:

Jokl suggested I should stay with them and help with the house, and he would bring me to school every morning. I don’t know whether this scheme will work, but I will try. Jokl suggested I go this week [to their house] and weigh the situation to find out if it will suit me because he says that Mrs Jokl thinks I might find it humiliating to take the place of a servant … The path to success is not an easy one.

Regina would ultimately refuse this offer in favour of the exhausting daily commute to Orlando—she had come too far to return to being a domestic servant in a white household. And once the logistical issues of money and accommodations were solved, Regina could prepare herself for the excitement of at last being a university student. Wits had previously offered a two-year diploma course in social studies that many of the Black individuals spearheading the new push toward social work had taken. For example, William Ngakane, husband of Mabel who headed the controversial Orlando Mothers’ Association, had completed this. By the late nineteen-thirties the university had inaugurated a new Department of Social Studies, part of the broader contemporary sense that massive urbanisation and industrialisation required a professionalised set of ‘scientific’ skills. The department was thus hybrid in nature, balancing academic sociology with practical training.

But unlike the Hofmeyr School, social studies at Wits stressed scientific methods—statistics was part of the course offerings—and religious teaching was entirely absent. It also lay at the heart of a powerful network of white liberals, leftists, and radicals at the university. It was staffed by figures like the sociologist Henry Sonnabend (whom Regina glowingly called ‘a lecturer and a half ‘ on account of his powerful oratory), an outspoken critic of the government’s policies toward Black South Africans. Social studies students also had to take courses in social anthropology with Hilda Kuper. Many South African anthropologists of the nineteen-forties—Kuper as well as Ellen Hellmann—saw their discipline as a profoundly applied one, a tool to further ameliorate Black living conditions as well as to critique the segregationist policies of the state. Kuper, for example, used her lectures to lambaste biological concepts of race as entirely lacking in scientific validity. Kuper also led groups of students to do research projects in Black townships, focusing on topics such as women liquor producers and formulating critical responses to government policy. The atmosphere could not have been more different from the stuffy, conservative Christian flavour of the Hofmeyr School.

Who were Regina’s classmates? In 1948, the year Regina graduated, there were sixty-four students in all the four years of the social studies BA programme, meaning she would have been in a cohort of around sixteen students. Most were women, part of the new influx of female students to the university during the war years. Presumably the female bias of the course also reflected the sense that welfare was a ‘woman’s career’. Regina would also have encountered a peppering of white female welfarists attending her lectures, including a doyenne of welfare work in Johannesburg: Edith Rheinallt Jones, founder of the Wayfarers, came with great dedication to lectures. And then occasionally there was a wife of a male faculty member who attended classes for they ‘had heard they may be stimulated’. Regina, moreover, was the only Black woman in the entire social studies programme and the first Black woman to ever achieve this particular degree. Almost certainly, she found few soul mates among her fellow students, most of whom were much younger than she was and many of whom were there in the spirit of a finishing school or for mental ‘stimulation’ rather than in preparation for future careers. The anthropologist Audrey Richards, who taught at the university in the late nineteen-thirties, had this to say of her female students: ‘All are very self-possessed, posé, and charming, but minds as blank as boards … The girls are beautifully dressed and I feel quite shabby, they look like a set of rose buds on a stalk.’

Rather than studying with the sweetly pink ‘rose buds,’ Regina had hoped to be placed with the African medical students for her science classes. (She was, for example, required to take botany in her first year.) There was even another woman in this group, Mary Malahlela, the first Black woman to train as a medical doctor in South Africa and who would graduate from Wits a year before Regina, in 1947. But to Regina’s dismay, a timetable clash made this impossible. So, Regina stayed with the white students for her botany classes, although with great reluctance. She told Dan a month after starting, ‘I am beginning to adjust myself gradually, icuriosity kubelungu iningi kabi [the whites’ curiosity about me is really terrible].’

Regina, however, did make at least one new friend at Wits. This was the soon-to-be-famous Ruth First, a fellow student in her social studies degree programme, with whom she would overlap with by two years. (First would graduate in 1945.) It tells us something about Regina’s burgeoning political consciousness and her rejection of white liberalism that it was First with whom Regina formed her most serious Wits friendship. First represented an entirely different kind of politics from that represented by liberals like Ellen Hellmann and Hilda Kuper. She was an active member of the South African Communist Party (her Eastern European immigrant parents had been founder members of the party in Johannesburg in the nineteen-twenties), and she was also romantically involved with a Wits Law student of South Asian descent, Ismail Meer. Both First and Meer would become important figures in the ANC. Indeed, First’s life would end violently in 1982 as she unwrapped a parcel bomb sent by South African apartheid operatives while she was in exile in neighbouring Mozambique.

Both her Communist allegiance and her interracial relationship placed First in a different world from the ‘rosebuds’ of the campus. First sat at the heart of a politically radical group at the university that included Meer, First’s future husband the Communist Joe Slovo, as well as Nelson Mandela, a fellow law student with Meer. Student politicians at Wits were inspired by the rise of populist Black-led movements in the city: First was one of several Wits students who volunteered for the miners’ strike of 1946, for example, which involved more than sixty thousand workers, and Wits students had also used their and their parents’ cars to give rides to those who boycotted the buses in 1944 (a protest against the high fares that devastated those who had to travel long distances into the city to work). In an interview with Tim Couzens in the late nineteen-seventies, Dan stated—not altogether approvingly—that it was during her Wits years that Regina ‘got mixed up with Ruth First and the Trade Unions’. This should not be exaggerated: we know from her letters to Dan that she was largely preoccupied with studies during her time at the university and that her political commitments would only come into fruition after her degree. But we can nonetheless see Wits as an important experience in exposing Regina to radical politics.

~~~

- Joel Cabrita is Susan Ford Dorsey Director of the Center for African Studies and an associate professor of African history at Stanford University and a senior research associate in the Department of Historical Studies at the University of Johannesburg. Her work focuses on religion, gender, and the politics of knowledge production in Africa and globally. She is the author of Text and Authority in the South African Nazaretha Church and The People’s Zion: Southern Africa, the United States, and a Transatlantic Faith-Healing Movement.

~~~

Publisher information

‘A bold, ambitious, and necessary project … An important and beautifully told tale of “sanctioned forgetting” and glorious remembering.’—Sisonke Msimang, author of The Resurrection of Winnie Mandela

‘A deeply compelling narrative that gives Regina Gelana Twala … the honour and recognition she deserves.’—Pamela Scully, author of Ellen Johnson Sirleaf

‘A gem of a story. Joel Cabrita … upends the notion that women are ignored because their works are obscure … Read the book to understand why.’—Shireen Hassim, author of The ANC Women’s League: Sex, Gender, and Politics

‘A significant contribution to African feminist scholarship and intellectual history.’—Ainehi Edoro, founder and editor in chief of Brittle Paper

‘Joel Cabrita has given us an exemplary historical biography that will have ramifications well beyond the boundaries of African history itself.’—Ato Quayson, Jean G and Morris M Doyle Professor in Interdisciplinary Studies and professor of English at Stanford University

Systemic racism and sexism caused one of South Africa’s most important writers to disappear from public consciousness. Is it possible to justly restore her historical presence?

Regina Gelana Twala, a Black South African woman who died in 1968 in Swaziland (now Eswatini), was an extraordinarily prolific writer of books, columns, articles, and letters. Yet today Twala’s name is largely unknown. Her literary achievements are forgotten. Her books are unpublished. Her letters languish in the dusty study of a deceased South African academic. Her articles are buried in discontinued publications.

Joel Cabrita argues that Twala’s posthumous obscurity has not developed accidentally as she exposes the ways prejudices around race and gender blocked Black African women like Twala from establishing themselves as successful writers. Drawing upon Twala’s family papers, interviews, newspapers and archival records from Pretoria, Uppsala and Los Angeles, Cabrita argues that an entire cast of characters—censorious editors, territorial White academics, apartheid officials, and male African politicians whose politics were at odds with her own—conspired to erase Twala’s legacy. Through her unique documentary output, Twala marked herself as a radical voice on issues of gender, race, and class. The literary gatekeepers of the racist and sexist society of twentieth-century southern Africa clamped down by literally writing her out of the region’s history.

Written Out also scrutinises the troubled racial politics of African history as a discipline that has been historically dominated by white academics, a situation that many people within the field are now examining critically. Inspired by this recent movement, Cabrita interrogates what it means for her—a White historian based in the Northern Hemisphere—to tell the story of a Black African woman. Far from a laudable ‘recovery’ of an important lost figure, Cabrita acknowledges that her biography inevitably reproduces old dynamics of white scholarly privilege and dominance. Cabrita’s narration of Twala’s career resurrects it but also reminds us that Twala, tragically, is still not the author of her own life story.