Anna Stroud chats to Jarred Thompson about The Institute for Creative Dying, his debut novel that imagines a radical alternative to life and death, which may appear less radical in time.

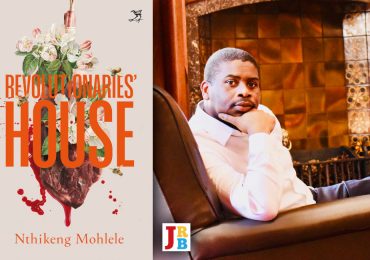

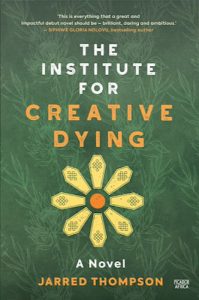

The Institute for Creative Dying

Jarred Thompson

Picador Africa, 2023

Anna Stroud for The JRB: It took me almost two months to finish reading The Institute for Creative Dying—I simply did not want it to end. I read every page, from the Dedication (would you like to tell us more about Shirley Dawn Steeneveldt?) and the quotations all the way through to the final Acknowledgements page. When I was reading the Introduction, I felt as if I was taking up residence in the unnumbered house between 8 and 10 Lancaster Drive in Northcliff. And when the narrator instructs the reader to:

Pick up your belongings with core engaged, pelvis tucked, back straight, knees slightly bent. That way you’ll be using your whole self, not just your arms.

—I felt myself sitting up a little straighter and pulling in my stomach. And for the next two months, I’d pause mid-sentence to write down a word or phrase that resonated with me. Jarred, thank you for the journey. But first, I have to know: what does your garden look like?

Jarred Thompson: Thank you so much for your hungry read of my novel. It’s comforting to know that three years of brainstorming, dreaming, honing and tinkering the story were years well spent. I wrote most of the novel at my parents’ home in Coronationville, by a window that overlooked our front garden. That garden is nowhere near the size of the one in the book, but it has its quirks and eccentricities (weaver birds and bee hotels included) that were reliable companions on my journey. I often turned to hiking and taking walks in parks to grapple with the kind of botanical expansiveness I was aiming for in the story.

Dedications, epigraphs and acknowledgments are interesting side-genres to novel writing. A dedication offers up the work as a tribute, sometimes to someone who tangentially has been pivotal in the shaping of the work. That person for me is my ouma, Shirley Dawn Steeneveldt, who at sighty-six still manages to hold on to her sense of humour even in the face of a crippling body and the early stages of dementia. My ouma is a beacon of perseverance and light-heartedness for me, someone whose story is like most stories—a distinct amalgamation of the extraordinary growing out of the ordinary. Much like what the institute attempts to show its residents, I think.

The quotations—each of which I felt I could not do without—were lines I had come across during the writing and thinking process. In their own way each quotation gestures towards some intuitive sense of what it means to be alive, whether that means leaping in hope of transformation, our inherent dependency on things outside of ourselves, our sense of deep memory in the world and the limits of our human knowing. All these questions emerged for me when contemplating issues of dying and living and how to write about them. As for dependency, a novel isn’t created in a vacuum—it emerges out of countless conversations and impressions gleaned from those nearest to you. The Acknowledgments are testament to that and so is the quote from the Introduction you mentioned above. Writing the novel made me obsessive about the body and how its postures and alignments, physical or otherwise, can cause us to pause, change our minds or feelings, and even allow us chances to be more comfortable within our own viscera. I was interested in how one works ‘with’ their body instead of ‘against’ it and the kind of patient lessons the structure of the body can continually teach us as these oscillating consciousnesses embodied in sinew and blood.

The JRB: Since its launch earlier this year, The Institute for Creative Dying has featured in Brittle Paper, 702, News24, Salaamedia, The Cheeky Natives, A Readers’ Community, and the Sunday Times, to name a few. Siphiwe Gloria Ndlovu said, ‘This is everything that a great and impactful debut novel should be—brilliant, daring and ambitious.’ And Rémy Ngamije calls you ‘one of the most promising voices on the African continent’. How does it feel to receive such positive responses to your debut?

Jarred Thompson: It feels like the culmination of a dream I’ve had since high school! One that is both humbling and daunting in equal measure. Humbling because all a writer can do is work on their craft, their process, and hope they can bring whatever is swirling within them to the page in a beautiful way. Daunting because dreams so often demand courage. To quote Koleka Putuma, ‘You owe your dreams your courage.’ A dream is one’s uncertain claim to the world; it orientates us to the future. All I hope is that I stay both grounded and courageous going forward.

The JRB: Your novel focuses on death and, inescapably, life. What texts did you read about the subject?

Jarred Thompson: I read a lot of essays on rituals of dying, limit experiences and psychedelic medicine and philosophy. Texts like Tracy K Smith’s The Body’s Question, Aldous Huxley’s The Doors of Perception, Elizabeth Grosz’s The Incorporeal: Ontology, Ethics and the Limits of Materialism and Michael Pollen’s The Botany of Desire were also influential in my approach.

The JRB: The novel centres around five people—Diane, Angelique, Lucas, Daniel and Tobias—who, with the help of Mustafa and the Mortician, discover different, more playful ways to approach dying. How does facing death challenge us to think differently about the way we live?

Jarred Thompson: To face death is, to paraphrase Tracy K Smith, to face the body as a question. What do you believe in? Do you believe that your soul is trapped inside this casing of flesh and is later released into a glorious afterlife when you die? Okay, what does that belief allow you to do in the world? How does it affect the way you relate to yourself and others? I do think our personal metaphysics—questions of existence and meaning—affect our ethics, how we act in the world. The novel is interested in posing different questions of belief about the body. Each of us face death intimately and individually and so it is this ever-present question of how you are going to narrate not only your life history but what happens to that history at the end, after you die. If we allow ourselves to think differently about the stories we tell ourselves about life—individual and planetary—I think we’ll be able to shift the way we live, even if it’s by a few degrees.

The JRB: One of the hosts, Mustafa, is deeply attuned to the environment and the people around him. Set in Joburg, a city where we are so conditioned to look away from people in need, he chooses to see and experience everything. In one scene, he gives a packet of food to a mother and her child standing at a traffic light. Driving away, he wonders to himself, ‘How to keep your heart open in hell’. Can you say more about this?

Jarred Thompson: In hell everyone has done wrong to someone else. Everyone has hurt and been hurt by someone else. The cycle of trauma is inevitably passed along for each of us to work with and hopefully subdue in some way. For Mustafa, whose life circumstances already condition him to a kind of ‘wandering in the world’, the way he works with the scars the world has inflicted on him is to remind himself to remain open to the world, to others, instead of closing himself up against others. With Mustafa, I was fascinated with how people we consider ‘holy’ have this openness to others, as if opening to others is a way for them to work on themselves. But I don’t think this ‘working on self’ is simple by any measure. Sociopolitical climates, structures of oppression and narcissistic individualism continually work, as you’ve observed, to separate us into our comfortable enclaves. Mustafa himself is no saint as he does some questionable things in the story. But I was interested in exploring this dynamic of ‘being open’ and ‘being closed’. When is it beneficial and when is it violent, not only to yourself but to others? Jean-Paul Sartre says ‘hell is other people’ but Lauren Berlant would argue that we cannot live without our need to be inconvenienced by the presence of others. Being inconvenienced by others reminds us that the fantasy of complete independence is just that, a fantasy.

The JRB: The second host, known only as the Mortician at first, understands the deep trenches that trauma leaves in the body. During her session with Angelique, a former model suffering from kidney disease, she says, ‘The body is a repository of niggles, things that have conditioned us from the outside. It’s a sponge, soaking up everything, holding onto the trauma in its tissues.’ Why is the theme of trauma important in the novel?

Jarred Thompson: I think trauma exists in gradations. It can be both ordinary and exceptional. We always seem to be living through some kind of crisis of the ordinary—loadshedding, water shedding, and so on—and that’s just us in South Africa. Trauma is that sense of the world ‘outside’ imposing itself on you in physical, emotional, and psychic ways. In part, these impositions shape us, but our response to trauma shapes us as well. Trauma is so often associated with how people get caught up in patterns of thinking, feeling and acting in the world and the institute is a place that tries to disrupt those patterns and, in that disruption, create windows for the characters to climb through to different iterations of themselves. Doing research for the book made me interested in the embodied ways in which we think and feel. How moving and manipulating parts of the body can activate moments of tenderness towards oneself that you may not have been able to access without that manipulation. Scenes of trauma call us back to the body always seeking homeostasis in a turbulent world. So I return to thinking about the body as a site where trauma is both stored but can also be released in some ways, albeit begrudgingly as trauma often instantiates the patterns of living we’ve grown accustomed to.

The JRB: Lucas is a former athlete whose successful career comes to a halt when he breaks his legs. He begrudgingly follows his partner, Daniel, to the institute and resists the Mortician’s teachings at first. Gradually, he begins to see it as a ‘place for experiment, where he was being allowed to shatter old habits and shock his system, discovering new ways to hold the world in his mind’. Would you say Lucas is the character who accepts her teachings the most in the end? Why him?

Jarred Thompson: Yes, if I were to write a sequel, I think Lucas would have to feature somewhere, especially given the reader’s final scene with him. Lucas’s history as an athlete has made him especially attuned to his body; he reminisces in one scene of his experience of entering a ‘flow state’ during a race—a kind of integrative, mind-and-body experience. His relationship to his body has been shattered when he breaks his legs and so his encounters with Mustafa help him re-understand himself; Mustafa helps him create a different story about his body. By the end, Lucas mourns the loss of a number of relationships and the Mortician stands out for him as the last person who might understand, to some extent, what he’s been through up to now. He stays for now, but that doesn’t mean he won’t outgrow her eventually.

The JRB: When speaking to Diane, a former nun who is terminally ill, the Mortician touches on the idea of ‘unconditional compassion’. Can you expand on this?

Jarred Thompson: I rewrote that conversation between the Mortician and Dianne several times. Each time it never seemed to be hitting the right notes, although now I’m reconciled to how it has ended up in the book. The reference to compassion echoes what Karen Barad calls ‘meeting the universe halfway’. There are so many unknowns in the world. Unknowns about the nature of reality. Unknowns about the most accurate picture of our psychology. Unknowns about why people feel, act and think the way that they do. When you think about the complex flows of force, matter and mind that we’re all caught up in, and from which we emanate, it can be dizzying. When the Mortician speaks about unconditional compassion, she’s speaking about grappling with the unknowns of ourselves and the world. How these state-of-affairs can surprise and disappoint us because we simply do not have as good a handle on things as we think we do all the time. This is where compassion towards our limitations on knowing comes in.

The JRB: Depression is another key theme in the novel, one that’s expressed most profoundly by Daniel, who describes it as: ‘… an unbearable stasis. A not wanting to move the pain, or the pleasure, around. When you’re in the thick of it, the simple pleasures start to look like a long arc of hurt.’ Why does he describe depression in this way?

Jarred Thompson: Daniel is the kind of depressive intellectual that rationalises feeling and phenomena in the world; he is attached to a scientific-rationalist frame of mind and the way he sees life leaves no room for wonder or surprise. So, when the pleasures of the world come along, he truly believes, in a very Schopenhauerian way, that pleasure is the exception and suffering the constant and he takes seriously the observation that all good feeling is temporary and must be continually repeated or replaced with more good feeling. This continual incitement to repeat one’s desire for greater modes of satisfaction is what wears Daniel out, to the point of an ‘unbearable stasis’. But Schopenhauer also has this idea of ‘the will to power’ that runs through everything in the world. Daniel’s depression, then, is this biologically-induced stunting of his will: a stunting of his ability to want to believe that things could be different. Daniel’s description of depression points to the ways our bodily pains and pleasures are written and understood in cultural contexts, to the ways the mind and body interpenetrate and affect one another in ways we don’t fully comprehend yet.

The JRB: One of my favourite characters, believe it or not, is the former convict, Tobias, perhaps because of his endearing relationship with the dog, Abbas. Tobias struggles to sleep in the ‘laanie hills’ of Northcliff. He describes this sleep paralysis as ‘papa waggies—when you’re asleep and you feel a spook sitting on your chest’. Where does ‘papa waggies’ come from?

Jarred Thompson: The nickname comes from a neologism I made from the famous anti-drunk driving advert that many South Africans know. In the advert a convict says to the camera, ‘Pappa wag vir jou’, as a deterrent to would-be drunk drivers. The neologism was a way for me to reference Tobias’s violent past and imagine a form of jargon passed between inmates at a prison. Throughout his life Tobias has been ‘held in place’ by his social circumstances, so much so that it even affects how he dreams and finds rest. His ‘therapies’ with the Mortician involve her own kind of ‘dreamwork’ as she attempts, not so successfully perhaps, to rid him of this haunting presence that reminds Tobias that all he’ll ever be is ex-con, scam artist.

The JRB: Tobias also says, ‘The world is too big for anyone to handle alone. I want to be done with it. Chew it up and spit it out. The same way it did me. The world’s ma se poes.’ Given all that’s happening in South Africa—loadshedding, corruption, poverty, vast inequality—how do you see joy, beauty and delight?

Jarred Thompson: Joy, beauty and delight are vital resources for living on amid the crises we find ourselves in. It goes to the heart of why all artistic forms are crucial for a functioning democratic society, I think. Such feelings, directed and informed in ways that are not solely hedonistic, can foster solidarity across difference. But the thing with joy, beauty and delight is that they’re temporary. Structures like inequality or loadshedding appear more persistent. So, while we may retreat to joy, beauty and delight as ways to lick our wounds from the overall disappointment of the political, so to speak, I think it is the continual longing for joy, beauty and delight that should make us ask tougher, more insistent, questions about ourselves and those who maintain structures of inequality for their own selfish purposes.

The JRB: Speaking of delight, I love your description of language as something that has ‘light in it, perceptible only by the objects it came in contact with. Without something to touch, something to obstruct their speed, words whizzed through space. Inert.’ How do you write? What is your process? What do you see when you put pen to paper?

Jarred Thompson: I’m not adept at any other artistic skill (although I can hold a note or two when singing) so language really is light and flesh to me. Light in the sense that writing is a way for me to really find out what I think about an idea, a character or a world. So I always approach stories from the vantage point of unknowing and wanting to ‘find out’ or be changed somehow through the writing of the story or poem. Writing adds ‘flesh’ to the ‘flash’ of inspiration that is sometimes an image, a phrase or a feeling. Language is fleshy for me in the sense that, while working on a writing project, I often walk around the room, take a walk, drive, or even exercise when I feel I need to move my body in order to think about a particular passage in another way. The editing process also features a lot of walking around and reading out loud to myself, which is where I am able to hear the cadences and rhythms of the prose.

The JRB: One of my favourite lines in the book is when Daniel decides that ‘this time he was going to write towards failure’. What does that mean?

Jarred Thompson: That line speaks to one of the epigraphs of the novel, Aldous Huxley’s observation: ‘However expressive, symbols can never be the things they stand for.’ Words are marks on a page that point to different aspects of the world and, in that, it is important to grapple with their limitations. To write towards failure is to begin the act of articulating the ineffable with the insane premise that you will already fail. Why else have poets been writing about love for centuries? We cannot help but put words to feelings. The thrill of the chase is that the ineffable always eludes. But in it eluding us it also incites us to ‘keep chase’, continually creating, seeking and imagining. This is the generative chasm of failure for me as a writer and it’s what writing the book taught me.

The JRB: In one of my favourite scenes, Mustafa watches a weaver building a nest and reflects on the fragility of life:

The nests were always temporary—torn apart by a male companion or worn down by the weather—and yet the weaver continued with the same dream, throughout the seasons, bringing the nest that much closer to perfection. Or maybe it wasn’t about perfection. Maybe it was about the thrill of imperfection: seeing how long one’s efforts held, how much of a home one made for oneself by the light one had to see by. It struck Mustafa, a tap on the shoulder, that life had a vein of insanity running through it—a desire to assail and subdue unknown wilds that always won out in the end.

What can one learn from nature on what it means to live—and to die? And could you please talk more about the ‘vein of insanity’?

Jarred Thompson: The ‘vein of insanity’ is that we, human beings, know how our stories end—with our heads blossoming into daisies. We know we all die but we keep on loving our children and pets or we keep on trying to perfect that recipe for sourdough. Deep down, I feel we have a deep care for life. Not just our own individual lives but life itself. And to be in care like that is to be implicated in understanding the need a lion has to tear into the back of a gazelle in order to feed, for instance. It is to be caught up in this ouroboros of life eating life, understanding it as a condition upon which we have evolved on this planet. As much as technology has taught us so much about comfort, convenience and the universe it has also acted as a barrier to tap into this wisdom of nature that does not speak outright in logical premises for us to easily understand. I’m not saying that ‘technology’ is bad and ‘nature’ is good as that is too simplistic, but so often technology pushes human society into extremes that have a detrimental effect on nature. To be able to make it through the Anthropocene, humanity is going to have to bridge the divide between technological convenience and nature. Biomimicry, a field of research where structures and systems are modelled on biological entities and processes, will become increasingly relevant in the future, I think. Not just for how we structure our societies but how we see ourselves in relation to the natural world, as beings intimately tethered to it.

The JRB: Finally, the novel focuses on the ethics of death and the laws governing the death industry. Why is the idea of delightful dying—and choosing how you die—such a taboo in modern society?

Jarred Thompson: I think it’s a combination of things: from the overly medicalised way that the dying and the dead are treated, to the religious doctrines that insist on holding on to life even when people are in extreme physical pain, to the multivalent effects that loss inflicts on those left behind. Willingly choosing how you want to die is not for everyone, of course, but that doesn’t mean it shouldn’t be an option for those suffering with terminal illness. On top of that, death is an expensive business and there is money to be made in coffins and the like. Really, questioning this taboo is about questioning the kinds of freedoms societies believe it can trust its citizens with. If our definition of freedom expands to people being able to ‘design their own deaths’ when they’re ready to leave, what kind of knock-on effect would it have on the responsibilities we have to stand up to social issues and make the world more hospitable for everyone? Daniel Callcut observes, if we are worried that such freedoms would make everyone want to ‘die delightfully’ then we should ask if we, as a collective human race, have made life on Earth so bad that death presents a welcome alternative. I think these are valuable questions to ask that pick apart this taboo and what traversing it might allow us to encounter. We need new communities of support for those dying or experiencing death in its many forms and The Institute for Creative Dying is my way to dramatise a radical alternative that I think will appear less radical in time.

- Anna Stroud lives and writes in Johannesburg. Follow her on Twitter.

This interview has been lightly edited for length.