Eye Brother Horn by Bridget Pitt is a South African novel immersed in our oral culture and traditions, writes Mphuthumi Ntabeni.

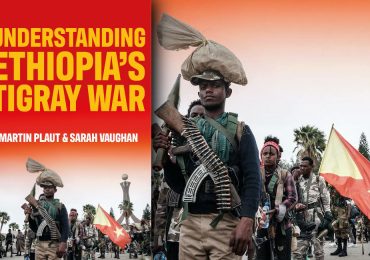

Eye Brother Horn

Bridget Pitt

Catalyst Press, 2023

Eye Brother Horn by Bridget Pitt is like an intsomi, a fable of biblical and mythological proportions. It therefore behoves me to begin writing about it in the customary manner: Kwahlala kwahlala kwang’ntsomi! A long time ago, white people were beginning to settle along the uKhahlamba (Drakensberg) mountains, along the banks of the Umfolozi River, a land forming part of the recently established Zulu empire. The land was under tremendous pressure, both natural and unnatural. It was a time of internecine colonial war and resistance to land dispossession. The white British Governor of the Cape Colony, Bartle Frere, fresh from his murderous rule of the small African island of Zanzibar, had become determined to end the protracted Zulu threat by exterminating the black tribes who refused to toil under British servitude. The events of Eye Brother Horn occur against this tense historical background, which culminated in the Battle of Isandlwana, wherein the Zulus decisively routed the British.

In those years the land was suffering a great drought, putting the numerous black villages at the foot of uKhahlamba mountains under tremendous strain to feed their people. In one of these villages, at this time, a woman gave birth to twins. There was then the widespread superstition that twin children were a bad omen for their family. In addition, the household felt it to be an impossible task to raise and feed not one but two children at the same time. As was common practice, so the story tells us, it was ordered that the weaker twin be left in the wild to die. The man who was given this task—a family member of the child’s parents—did not have the heart to dump a helpless newborn to become carrion. After wrestling with his conscience, and overtaken by pity, he resolved to face whatever consequences would follow after defying his orders. He decided to take the child to the newly established Christian missionary. There he informed uMfundisi in charge, Reverend Whitaker, that he had found the child on the banks of Umfolozi. The reverend and his wife resolved to take up Kipling’s ‘white man’s burden’, raising the boy in civilisation along with their own son, who happened to be of the same age. Imagining the child to have been found among the reeds, they named him Moses. Their own boy was named Daniel. Thus Moses, like the injured fledgling his mother rescues, which is adopted by one of their hens, becomes ‘an owl raised by chickens that still knows itself to be an owl’.

Moses grows to be of strong stature, physically and intellectually. He has a bright and curious mind that leads him to be interested in science. Daniel, on the other hand, is a sensitive and delicate type who feels deep compassion for the environment and abused animals. As a baby, he has a near death encounter with a rhino, which instead of impaling him seems to succumb tamely to his aura, leaving just a small graze on his forehead, and leading people to speak of him as ‘inkonyane likabhejane: the Rhino’s child’. On hunting parties he literally feels it in his own flesh when animals are killed. He develops a mythical connection to the land and its animals, and his life is often threatened in defending them.

When he gets older Daniel consults a sangoma for a cure to his apparent ailment. The sangoma tells him he has to kill a rhino and rub the powder from its horn into cuts on his own body:

The blood and horn will enter your skin and make you as hard and impenetrable as the rhino horn. But I warn you, it will harden you in other ways too, harden you not only to the suffering of animals but also to the suffering of other humans.

But, when presented with the opportunity, Daniel cannot do it:

He can’t harden himself to the suffering of others. He’s been chosen to carry it, this awkward, sorrowful legacy. Chosen when Joseph picked up Moses. Or when the rhino spared him—or wherever it came from. He doesn’t know what the ancestors are asking of him. But feeling the suffering of animals is part of it, for that is how they are making their own distress felt. And he knows this is his thing, and carry it he must.

Despite its themes of environmentalism and morality, Eye Brother Horn mercifully steers clear of becoming preachy, as these are not messages but details contained within the story. Even the clash of spirituality and religion is not didactic, but rather played out through the lived experiences of the characters and their development. Though the book is permeated with biblical allusions, these serve simply to form and fill the tapestry of the story, and the novel declines religious contemplation that may have become laboured.

When they grow up to be young men Moses and Daniel are required by their father to work on the sugar plantation belonging to his wealthy English cousin. This way, their father hopes, they will earn their way for Sir Roland to sponsor their further education in England. Daniel wants to become a missionary, while Moses surreptitiously wishes to become a scientist. But the moment the pair set foot outside of their Edenic existence on the mission, they are forced to encounter the reality of the world and the era. No longer is Moses allowed to treat himself as Daniel’s brother and equal. On the sugar plantation he is required to take on manual labour with other black people—which he considers preferable to lording over his fellows. He loses his honorary white privileges of dining at his master’s table or sleeping in his house. He is required to sleep with the other labourers, although Daniel visits him almost every night to escape Sir Ronald’s condescending racial and greedy capitalist attitudes:

It’s all in your attitude, my boy. If you can look at a piece of land and see ahead to the wealth that can be turned from it, if you can put in the hard work to see that wealth created, you’ll go far in life. This is what distinguishes the British from the African native. The natives are content to grow enough merely to feed themselves. A true Englishman wants more. If you don’t want more, my dear boy, you’ll get nowhere in the world.

After a time on the plantation, Moses is falsely accused of assaulting his white supervisor—a drunkard—and given six lashes. He preaches a political sermon about equality and resistance to the other farm workers, and is accused of leading the men astray. Sir Roland also believes him to harbour undue influence and power over Daniel, whom he regards as a weaker character. Moses is a threat to the white man’s hegemony, and his life is made a living hell. Daniel shows some resistance to the manner in which Sir Ronald treats Moses, which further estranges him from his uncle, but he is unable to convince Moses that the two of them should leave the farm. Moses holds an attitude of strained resignation, focusing on the bigger picture of their prospective studies in England, and adopts a compliant attitude towards his racist tormentors. Soon enough, however, the promise of sponsorship for this education is broken, and Sir Roland insists he will only pay for Daniel, his blood relative, despite Moses being, as Sir Roland admits, ‘a far worthier candidate’:

He’s not my cousin’s child in any way I recognise. And, thanks to my cousin’s misguided experiment, he is infected with an unshakeable conviction that the white man is no better than the black. I can see it in his eyes every time he looks at me. He could have been a real boon to the colonial cause, but your father has ruined him. His qualities might go far in an Englishman, but they’re disastrous in a native. He is already a danger to the colony. Educating him further would make him deadly.

Daniel revolts on his brother’s behalf, refusing to go on a hunting expedition with Sir Roland—the hunts that have been emotionally and physically scarring him. Sir Roland, who has been hunting indiscriminately, killing wild animals for sport, is in thrall to the power he has behind the rifle, and wants to kill more rhinos. Daniel calls him an ‘isiququmadevu monster who laughed in his beard while eating up the land and all that lived on it, human and non-human’.

Daniel snaps. He becomes possessed by the animating spirit of the wild, the rhino in particular, with tragic consequences:

The last time Moses saw Sir Roland, he was being sewn into a buffalo skin, his bloodied face a mask of incredulous outrage. They carried his corpse for ten days to the border authority at Nonoti, first on the shoulders of the bearers, then in the ox wagon—the men hadn’t wanted to bury him, in case they were blamed for his demise.

If this brings to mind the final demise of David Livingstone I am sure the winking suggestion is deliberate.

Moses loses everything, including his hope for educational sponsorship and the love of his adopted parents. His father, after reading Sir Roland’s last letter, which Moses honourably delivers despite knowing it wrongly condemns him, accuses Moses of paying his parents back in evil the kindness they showed him. Moses ultimately pays his own way to England, without ever seeing Daniel again.

Eye Brother Horn is narrated delicately, notwithstanding its (pleasing) anti-imperialist tone. The book reflects a Zulu worldview and culture, and plants, rivers, trees, and so on are mentioned by their Zulu names—the umsinsi tree, the umkhiwane tree, the isibhaha tree. Zulu phrases pepper the narrative, a game attempt at providing an indigenous aspect, even if sometimes it feels clunky or wrong-footed.

My main—slight—critique of the book involves the manner in which it shies away from discussing in depth the complex nature of its characters’ experiences, their inner psychological world, thus, unfortunately, sacrificing depth for comprehensiveness. The novel would have gained gravitas with a little deeper digging into the philosophical nature of its themes. As it stands, it has a tendency at times to read like a novel for younger readers. I suspect this was a deliberate authorial decision—perhaps to attract the likes of Greta Thunberg or Leah Namugerwa to its cause. That being said, the issues book tackles are pertinent and timeous. Mercifully, the novel is free of condescending anthropological assumptions about Africans, and its subversion of stereotypes is notable. Eye Brother Horn is a South African novel immersed in our oral culture and traditions, which undertakes to appreciate them from within their living spirit.

- Mphuthumi Ntabeni is a political commentator and writer who lives in Cape Town. His debut novel, The Broken River Tent, won the 2019 University of Johannesburg Debut Novel Prize. His second, The Wanderers, was published in 2021.