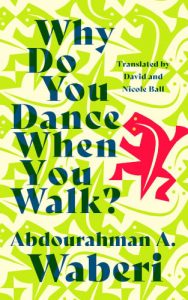

The JRB presents an excerpt from Why Do You Dance When You Walk by Djiboutian novelist Abdourahman A Waberi, winner of a 2021 English PEN Translates Award.

Why Do You Dance When You Walk

Abdourahman A Waberi (trans. from the French by David Ball and Nicole Ball)

Cassava Republic Press, 2022

Read the excerpt

I met your mother Margherita six years before you were born. It was in Rome, the city of eternal love. I had just turned forty. I was a dashing forty-year-old and I had already written several novels. Your mother, Béa, was so beautiful she looked as if she’d just stepped out of a painting by Raphael, but don’t worry, she’s as splendid now as she was on that very first day. I was starting the promotional tour for the translation of my fourth novel into the language of Dante. I was to meet the press and give a public reading as part of a series of gatherings called ‘Reading Africa’, before going to Bologna and Torino.

I met Margherita in a very small bookstore devoted to the arts and literature of the African continent that your mother had the good idea of starting, with the help of a few women friends of hers. You’re going to tell me you know all that already, Béa. But your mamma couldn’t—or wouldn’t—tell you that behind the artistic pretext for the Libreria Ebano, there was another, more prosaic reason: give an occupation to Carlotta, your future grandmother, newly retired and so prone to melancholy. Carlotta cursed Roman life, too exhausting for her taste. She wasn’t wrong, you know. Arguing with a taxi driver is enough to ruin the reputation of the papal city. A thousand jokes about the Romans are always going around in Italy. They make fun of those crude, impatient, loudmouths. Everything about the Romans is a source of laughter—their dirtiness, for starters. My favourite joke sounds like a riddle. I’ll give it to you verbatim:

Who’s more useless than a garbage collector in Rome? Einstein in the land of charlatans. From that, the jokes are strung together like pearls in a necklace. Who’s more religious than a Roman? Another Roman, of course!

Carlotta ended up leaving Rome for Milan, where Margherita was born. We go there as often as possible. From the time you were very young, we travelled a lot so your tastes and your curiosity could resonate with the diversity and the mysteries of the world. We wanted you to grow up with a wanderer’s spirit. Do you remember David and Abigail, the researchers from Boston? The couple who lived with us when you were five or six? You were very attached to them. From the very first day, you turned on the charm and in a very short time became their accomplice. Hardly had they set down their bags than you bombarded them with questions about their clothes, their country, and what they usually ate. Some people, Béa, are deeply moved by the reality of others, by their way of speaking or lighting a cigarette, or by their table manners. There are others who observe the world with a detached eye. You obviously belong to the first circle. You welcomed our American friends. You were playful and teasing, like when one of your friends came to sleep over. Sometimes they didn’t answer you because they didn’t know what to say. Once, when you asked them if they’d seen me biking in the streets of Boston, where I’d lived for two semesters just after meeting your mother, their silence grew heavier. You pretended not to notice their embarrassment. Then you tried again, diretto, as if nothing was the matter.

Americans are very gentle, especially with children. They’d listened attentively to your questions all week, prompting you with the English words missing from the vocabulary of a naughty little girl. We, your mother and I, did notice their confusion. From her post at the stove, while peeling succulent Sicilian tomatoes, Margherita was eavesdropping. As for me, I didn’t want to butt in. I limited myself to my role as host first, then guide. I wanted them to see the new Parisian spot, from Saint-Ouen to the fallow fields of Bercy. I must confess you had caught me off guard. I hadn’t imagined for a second that you were going to ask about my competence as a cyclist.

You wanted to know if they’d seen me pedalling in the Boston suburbs. I can tell you the answer Abigail and Dave couldn’t have given you. The answer is no. At five, you couldn’t be clear about it so your curiosity was natural. What’s more, you had never seen me on a bike or a scooter. Nor on a ski slope. Now you know the answer. No, I still don’t know how to ride a bike and I never had the courage to venture out on a skateboard.

The polio that weakened my right leg at the age of seven kept me from all those activities. But, as a bonus, I inherited that rolling gait. I don’t know how to ride a bike. But I like to dance. As a student in Rouen, I sometimes danced in front of the windowpane in the hall of my dorm, with a comb stuck in my Afro. Oblivious of everything else, I swayed my hips to the rhythm of the dense moaning of Otis Redding or the meowing of Michael Jackson,

Yes I like to dance. So I dance.

I dance even when I walk. Without

thinking about it. It’s second nature.

It’s my signature.

For three nights in a row, Abigail, Dave and I went club hopping. The last night, just before their departure at dawn for Logan airport, we had the time of our lives. On a barge transformed into a nightclub, we had the privilege of admiring liana-women parading before us. Each more beautiful than the last. Perched on geisha shoes that made them look like ibises on springs. I’m telling you about the ibis, Béa, because you’ve loved that royal bird ever since you discovered it at the Paris zoo when you were little. After the barge closed, we took a taxi for a last turn around the dance floor. There, we danced, again and again, jumping in the air like little brats leaving the schoolyard on the last day of the school year. No point apologizing when you bumped into someone in the crowd: the electro music was so loud that it covered the sounds and isolated the concert hall from the neighbourhood around the Bastille. Stromae didn’t have to ask us to dance. As soon as we recognized the first measures of his hit Alors on danse we threw ourselves onto the dance floor and never left it.

No need for encouragement.

I dance as I walk.

I walk as I dance.

It’s lasted for over thirty-eight years.

I’ve fully accepted my rolling walk.

To say it in Stromae’s words, I find myself fantastic. Fantastic, and

absolutely not pathetic.

In the midst of the crowd, I had eyes only for Stromae’s choreography. I knew every step, every move of the hips, every mimic of the half Rwandan-half Flemish maestro. Let me make one last confession, Béa. I had met Stromae in Rio two or three years before. We even had kept a little epistolary relationship everyone thought flattering for me. Stromae was friendly enough to send me an invitation card from Brussels. This whimsical artist is a man of his word. He had promised he’d invite me as soon as he was back in Paris. And he kept his word.

The winks of the gazelles had no effect on my friends and me. We were there to sweat blood and dance till the small hours of the morning. I don’t know if Stromae saw us. We danced like crazy, my little group and I. Our fervour increased tenfold when Stromae asked the crowd what piece they wanted to hear. Like one man, the crowd shouted: ‘Papaoutai’. This piece works like a charm. It opens hearts and unites parents and kids. Of course, the audience took up the song a cappella. Everyone knew the words. I know you love that song, too, Béa. When I was away, you’d sing it to me on Skype. Whether or not Stromae spurred us to dance, I thought of you on the dance floor, my darling. I had you under my skin, my sweet little girl!

Where’s your dad?

Tell me where’s your dad?

Without even having to talk to him

He knows what’s wrong

Oh my dear father

I was mad with joy, yelling along with the overheated audience. David and Abigail were in heaven, too. We applauded so much our hands were numb for a long time after the piece ended.

Suddenly, I thought of my parents. My mother’s features came into focus on my retina, like a non-digital photo fresh out of the stop bath. I think she was encouraging me to keep on clapping. My father looked hieratic, silently staring at me with his watery, old man’s eyes. Our non-verbal exchange stretched out and deepened. At his sides, my Grandma Cochise and my aunt were conferring. They were blessing me, I think. In the background, Ladane was there, too. Luminous. She winked at me and then sent me a burst of positive vibes, to use one of your favourite expressions. Too bad you and Margherita couldn’t witness my emotion at that moment. You were fast asleep. Margherita in foetal position and you, surrounded by your two cuddly elephants with Obama-like ears.

I danced a saraband with my parents.

Their love dissolved my old fear.

For four decades fear had been by my side.

It was high time it let go of me.

- Abdourahman A Waberi was born in 1965 in Djibouti. He teaches French literature at the University of Washington. He has written pieces for Slate Afrique, Le Monde and other newspapers and is the author of numerous books, including Le Pays sans ombre (1994), Cahier nomade (1996), Balbala (1998), Aux Etats-Unis d’Afrique (2006) and La divine chanson (2015).

~~~

Publisher information

‘Papa, why do you dance when you walk?’

When Aden’s eight-year-old daughter asks him this one morning in Paris, he is taken aback. The question is innocent, but the answer is not so simple. Unable to resist Béa’s inquisitive spirit, he moves silkily between memories of his childhood: from his silent, mysterious mother and the shanty roofs of his neighbourhood to the malicious attack that changed his life forever and the ensuing struggle that made him a man.

Anchoring his memories is a Djibouti on the cusp of independence; a land of shifting deserts and immense heat, French-from-France expats, and one immensely lonely and sick boy finding solace in books.

Why Do You Dance When You Walk is a poignant and timeless story of the complexity of family, the value of poetry and freedom, and the trauma we inherit from those who came before us.