Carey Baraka reviews The House of Rust, the latest tale from Mombasa, land of fables, and chats to its author, Khadija Abdalla Bajaber.

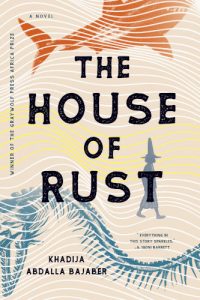

The House of Rust

Khadija Abdalla Bajaber

Graywolf Press, 2021

The writer Khadija Abdalla Bajaber is a busy person. In October 2021, her debut novel, The House of Rust, was released, a fabulist coming-of-age story set in the Kenyan coastal city of Mombasa. The book, which in manuscript form won the inaugural Graywolf Press Africa Prize in 2018, was launched at Alliance Francaise in the same city. But even before this launch she was thinking about another novel. Months prior, she had been sequestered in Tanzania (in a safe house deep in the middle of nowhere, she texted me) working on a novel, which, she said, would also be set somewhere along the East African coast.

Here now, already, was The House of Rust. A silky book, whose prose dances in an Anglicised Swahili, and whose characters battle in proverbs, it is the culmination of a dream Bajaber had long held: to write a fairy tale about the city where she’d been born and grown up. ‘How cool would it be to read a fairy tale taking place in my home town?’ she’d wondered. ‘Everywhere else gets romanticised, what about Mombasa?’

On the shores of the Indian Ocean, built on a coralline island, Mombasa has existed for centuries—perhaps a millennia, or more. Bantu communities first settled along this stretch of coast, before waves of explorers, fishermen, traders, soldiers and colonialist-missionaries came. Here a queen reigned in the time before Islam—Mwana Mkisi. The name of the settlement she founded, Kongowea, is an aberration of the word Kongo, which means ‘a place of civilisation’. Her dynasty lasted for centuries. Then came Shehe Mvita, who deposed her dynasty, and was the island’s earliest recorded Muslim ruler. In present-day Mombasa, two areas called Kongowea and Mvita still exist, anchors to an extant past.

Conventionally, Mombasa’s origins are traced back to 900 AD, but the first hint of a possible mention of the city occurs eight hundred years prior, during the first century. In the Roman historian Ptolemy’s Geography, there is the vaguest inference of it. In the book, a sailor called Diogenes, on his way to India, is blown off course to a mysterious town along the East African coast he called Rhapta. Rhapta’s true location remains lost to us, but there are theories. The strongest suggest a location on the mouth of the Rufiji River in present-day Tanzania that drains into the Indian Ocean. In Diogenes’ account, this river’s source was the Mountains of the Moon, next to the swamp that was believed to be the source of the Nile. But it could have been one of the other city-states on that stretch of seaway. Kismayu. Lamu. Malindi. Kilwa. Mombasa.

In The House of Rust, there are hints of this history: Almassi, ‘a war god, a death god’, roams the land for centuries, killing and taking as he wants, before being trapped in Mombasa by a spell. Another character offers an even older history of Mombasa. He tells Aisha, the Homeric hero of the novel, about the jinnis that were of a time before the town existed:

‘In the old time, in the long days, the jinnis of the sea moved freely and spoke and lived among the jinnis of the land. Sea and land and sky, merely provinces.’

There are many stories of Mombasa. For now, we stick with the one that gets us here. We see mentions of the town in the writing of the Arab geographer Al Idrisi in 1151. The Moroccan scholar Ibn Battuta visits in the fourteenth century, describing it as ‘a large island’ whose ‘trees are the banana, the lemon, and the citron’. Then more visitors. The Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama in 1498; and a horde of Portuguese soldiers two years later. More Portuguese attacks; the burning down of the city by the Portuguese; the building of Fort Jesus, and attempts to establish a Portuguese colony in Mombasa. These periods of Portuguese rule were interposed with periods of Omani rule, Zanzibari control, and British colonial rule. Then, in 1963, Kenya declared its independence from Britain, and Mombasa became part of the new state.

To visitors today, Mombasa takes many forms. In the most common, it is a tourist city, famous for its sunny weather and the white sand of its beaches. Its buildings are odes to different architectural traditions: sixteenth-century Portuguese architecture is distinct, as is the Middle Eastern influence of its narrow streets and high houses with carved balconies; and there are cathedrals built in Anglican and Roman styles. The oldest parts of the city lie on Mombasa Island itself, but it extends onto the mainland, separated by the stunning blue water of Port Reitz Creek to the south, and Tudor Creek to the north.

Once upon a time, there was a girl in Mombasa. She did all the things that girls like her do. She went to school. She played sports. She attended madrassa. She laughed. She cried. She imagined. She grew up.

Early on, writing was not a conscious desire. It wasn’t something that struck Bajaber as something a person could want to do. It wasn’t until she was eleven that she realised that people could write recreationally. Then she started writing. She never finished these stories, but she enjoyed the process of coming up with them. The stories she created were informed not only by the Mombasa she saw around her—the ocean, the boats and fishermen, the crows on the awnings of houses, the stray goats on the street, the oral narratives of the city—but also by the books she had started to read and like. She loved Jonathan Stroud’s The Bartimaeus Sequence, and Malorie Blackman’s books. In school, she read George Bernard Shaw’s ‘Pygmalion’ and Shakespeare’s ‘Julius Caesar’, both of which she loved, and John Fowles’s The French Lieutenant’s Woman, which she hated so much that she ended up not studying literature. There was also a big Mario Puzo phase with The Godfather books, as well as a Jane Austen phase—her favourites in the oeuvre were Mansfield Park and Persuasion but she disliked Emma (‘I know it’s the favourite of the intellectual’) and Northanger Abbey. In addition, she read a lot of books written by Asian writers, most of whose names she can’t remember.

In the period around the end of high school and the start of college, Bajaber began writing semi-seriously. She wrote poems, and read a lot of John Keats, who was a big influence on her work. In addition, she’d read and reread Joseph Heller’s Catch-22, which she found extremely funny. She’d moved to Nairobi for college, but after graduation moved back to Mombasa. There, she started sending out her work to literary magazines, first poetry, and then some fiction too. Then, one night in 2018, her big break. She was at home playing a video game on her computer when she received an email from Graywolf Press. Her first instinct was that it was a rejection. It wasn’t. The manuscript she’d sent to them—the one about a girl from Mombasa—had been selected as the winner of their manuscript prize. She cried. She called her parents on the phone. Her mother’s happiness was so pure it made her cry some more. She hadn’t told either of her parents that she was applying. A few months later, when Graywolf Press made the news public, her life changed. A deluge of calls to her phone; relatives, friends, and people from Mombasa she knew only from a distance. Remembering this period, she says, ‘I felt like my world was ending. You feel a lot of love, but also at the same time, please leave me alone. Don’t make a big fuss out of this.’

Where once Bajaber was just a girl in Mombasa, now she had metamorphosed into something larger: the city’s writer.

*

As a child, learning to swim, Bajaber had gone out every morning with her father. I ask her whether they’d swim in a swimming pool, or in the ocean. She laughs. ‘In a pool,’ she says. ‘I’m not brave enough to swim in the ocean. Asubuhi? I’ll get eaten.’

Seas, Bajaber told me once, months before the release of her book, exist to disappear the fathers of protagonists. We were talking about Yvonne Adhiambo Owuor’s The Dragonfly Sea, and how both the fathers in Owuor’s novel and her own were lost to the seas. In The House of Rust, Aisha’s father, a fisherman who made his reputation by catching deep sea fish, fails to come home one day. Rather than sit inert at home waiting for her father to return, in the manner expected from her as a girl (‘orphans, widows, women were expected to scan horizons till their eyes hurt, so that if her father came she would be there to greet him, a good daughter, a good wife, a good mother, a good host’), Aisha sets out to sea herself, sailing from the algae-mossed shore of Tudor Creek one night.

It is easy to think of The House of Rust as a feminist text (because it is, after all). Much like Tanzanian writer Elieshi Lema’s Parched Earth, its protagonist is a young woman/girl in a conservative East African community with a disdain for tradition for tradition’s sake. She talks back to adults. She refuses to get married. She expresses a desire to be a sailor, which to the local community is a man’s profession. Her father is the only person who allows her into the water, but even he has found an excuse to forbid her from going into the ocean with him. Aisha, like Parched Earth’s Doreen, rebels against the ideas of femininity she is being cloistered into by the society around her. Thinking about Aisha, Bajaber tells me, ‘You’re a girl but you’re also being prepared for entry into womanhood. You can’t just be; you have to figure out what kind of shape you’re going to take as a woman.’

Aisha’s sole companion as she ventures into the Indian Ocean is a talking cat, Hamza. Hamza hails a ship made out of bones by singing to it. Aisha rows in the stillness of the night, and the oars make no noise. The sea does not sleep, the cat tells the girl, and there are things in the water that would eat you alive. Aisha meets these things. A mysterious immortal sea creature, which had been her father’s hunting companion, and which had wanted her as its betrothed, a child bride. The Sunken King, a boy made of white marble rising from the dark depths of the water. Baba wa Papa, the king of sharks. The sea Aisha and Hamza travel to is an unnatural sea, a sea that, unlike Mombasa’s, ‘blew no wind or sail, the kind of sea in which nothing moved’. This is the undersea. In this sea is Aisha’s father, trapped, or, Aisha’s grandmother believed, already lost and dead.

The House of Rust first came to Bajaber one night during a power cut when, in the boredom of the dark, her mother asked her to tell them a story. She already had the first inklings of Aisha’s story, and she started there, then, her family enthralled by the narrative, and added more to it, spinning the fairy tale along. On this night, The House of Rust existed as an oral narrative, but soon it existed on paper too. Bajaber put all her other projects aside in favour of writing out that first chapter. When she was done, she was struck by how perfectly it fit together, so perfectly in fact that she began to doubt her capacity to end it.

Even though that night with her family had inspired her telling of the story, she kept the fact that she was writing it down a secret from them. She didn’t need the pressure, she says. Instead, she focused on the narrative, which felt like it had always existed in her. Here was a story about Mombasa, about the sea, about a girl called Aisha who was Hadhrami—Yemeni—like Bajaber herself, and going on a quest. Bajaber had always loved the sea, and loved Mombasa, but she felt that she was not good enough an oral storyteller for the story to be narrated in conversation only. Had she been, she would never have written it. Writing it was a way to find the language to express what she felt for her town, a love that had made her dizzy for most of her life.

An early draft of the book ends at what is now its halfway point, at the end of Aisha’s voyage to rescue her father. Only after Graywolf Press had acquired the novel did the location of the title, the House of Rust itself, a mysterious place in which Hamza promises Aisha she can find the secrets of life, emerge.

Even now, months after the book was released, Bajaber doesn’t think of Aisha as a hero. To her, Aisha is a navigator who thinks herself trapped, and struggles to find her way out, searching for freedom. Her quest leads her to revelations about the eerie machinations of Mombasa, but it also lets her be free to explore the sea, to explore herself. ‘I wanted wonder, adventure,’ Bajaber says. ‘Dutiful girls don’t go on adventures in the night, don’t take those wild, fairy tale risks.’

She adds,

When Aisha goes to sea, she’s scared, but she thinks something along the lines of being eaten by a monster was less dangerous than accepting the kindness of Hassan, less dangerous in that the consequences of the former were clearer and thus less insidious. She’s very wise and rather cruel to herself in that moment. And to me, that was what was most interesting—the grand adventure at sea is fun to read, or cumbersome, depending on the reader, I don’t know. But the sea adventure is not the heart of the story.

For Bajaber, the danger Aisha faces while on that boat isn’t the sea itself. Rather it is how she barters away parts of herself, sometimes knowingly, other times without understanding the risks of losing those parts. A lot of these partings appear mundane, the shoes she gives away to the sea, for instance, a minor transformation, while others are more significant, such as her eagerness to eschew the wishes her grandmother had for her life. Aisha doesn’t understand what these transformations will cost her. She has to go and rescue her father to understand.

*

In the contemporary oral history of Kenya, Mombasa exists as the land of fables, some fantastical, like those of supernatural encounters with jinn, others realist, tracing their sources to historical events. A lot of Kenyans, especially non-Coastal Kenyas, watu wa bara, have stories about a run-in with majini whose veracity they swear upon. These stories, deeply embellished, are always set in Mombasa.

My personal jinn story emerged from a secondary source when, in primary school, the school librarian, a man who had grown up in Mombasa, told us how his best friend disappeared when the two of them went swimming in the ocean one day. Presumed dead, this best friend turned up years later and asked Athumani, our librarian, if he wanted to see where he’d been. Athumani said yes. The two went to the Indian Ocean and waded in. Underneath the water, there was a dry cave, and a woman who had kept Athumani’s friend with her for years as a servant. This woman was able to make a person breathe underwater. She was an ocean jinni. She asked Athumani if he wanted to stay. He fled and swam to the surface as fast as he could.

I joke to friends that Athumani is responsible for my enduring distrust of Mombasa. It is only a half-joke. Often, majini are shapeshifters, adopting the bodies of animals when it suits them. In Kenyan media, there are multiple reports of these spirits. Here, kids in Mombasa are warned against kicking cats, dogs and rats in the daytime, lest they are attacked by majini at night. Here, tenants flee a rental property in Mombasa, claiming the houses are haunted by majini. In certain online forums, traders claim to sell majini that will help you become rich.

In Islam, the jinn is made of smokeless fires. The East African coast’s centuries-long relationship with Islam meant that certain Muslim beliefs meshed with local ones and became part of the local oral tapestry. In the Mombasa Bajaber grew up in, the tapestry of majini was very visible. She tells me about how, when she was a child, there were a lot of goats on the streets of the town, herderless. She wondered why nobody would steal the goats. Then she’d hear stories. Once there was a guy who stole the goats and put them in his truck. Driving off, he heard a commotion, so he stopped in the middle of the road. He opened the back of his truck and there were all these naked people sitting on their haunches. They looked at him and said, ‘Turegeshe pale ulipotutoa’ (‘Return us where you got us’).

‘How bizarre is that story?’ Bajaber asks me. ‘It’s so scary and so funny but completely believable.’ She laughs. ‘There’s something about it. If I could distil it. It just feels so Coast to me.’

The majini also showed up in her book. Aisha’s grandmother tells her stories of upcountry folk being punished by beautiful women with hoofs peeking beneath their buibuis, of crows throwing murderous parties and guzzling blood like palm wine, of blessed virginal heroines and their prize of a prince. There are also the goats Aisha chased, herderless goats whose master is revealed to be Almassi, the death god. Then there is the cat, Hamza. In the most common version of the Mombasa majini story in Kenyan oral tradition, cats in Mombasa are often actually jinns who will reveal themselves to you in their wrath after you give offence to them.

‘The cat, I never specified if he was a jinni,’ Bajaber tells me, ‘or just an animal which developed human consciousness and intellect.’

She was leaning towards the latter, she says, but she didn’t want to specify either side, since she didn’t want to write about things she doesn’t know about. ‘As much as you can play with fantasy elements, you need to figure out what is real and what will have consequences,’ she says.

Cats, Bajaber tells me, are chilling animals. If you hear them yowling at night, it sounds demonic. She smiles. ‘But then cats and crows, when you see them in Mombasa, I feel very at home. They’re not scary for me. You go to restaurants, or you go for nyama choma, and mapaka kila mahali. Some of them are mean, some of them try to bembeleza you for food.’

She liked the idea of a cat that lives above ideas of ownership. It’s nomadic in nature. It goes wherever it wants. It does whatever it wants. It decides if it will let you love it. So she came up with Hamza. Hamza is not a beautiful animal. He looks like a beat-up alley cat. He is skinny and scrawny. When Aisha first meets him, she takes pity on him, and leaves out food. The pair go years without seeing each other. ‘I have waited so very long for you,’ the cat says to her. ‘Have you forgotten me? Where is my share?’

Shocked to find an animal talking, Aisha thinks the cat is a devil. She prays under her breath, ‘I seek refuge with God from the accursed devil.’ The cat does not flee from the power of her prayer. ‘I am no jinni,’ he reassures her.

Reading The House of Rust, one understands that its author is winking at the reader. The fantasy is clearly fantasy, but the writer’s capacity for world-building means that the fantasy is not clearly fantasy, that everything is real. In real life Mombasa, after all, we watu wa bara know that stray cats are rarely just cats. Playing with these elements has real-life consequences. Even Bajaber, who tells me, ‘I don’t need to know about majini; I just need to respect and stay in my lane.’

This Aisha does not do. Aisha is not the kind of girl who lets things be and stays in her lane. Her mother was called Shida, Swahili for ‘problem’. Aisha is shida itself, possessed by what the regal shark hunter Zubeir calls the ‘half-feral heart’ her mother had.

Part of Aisha’s struggle is that she is fighting two fights: fighting a sea that throws different monsters at her, and fighting Mombasa’s history, the history that makes her love the city, but constricts her at the same time. In Mombasa, first, there was the dynasty of Mwana Mkisi, and the lineages that come from her—Thenashara Taifa (Twelve Nations). Aisha’s grandmother, Hababa Swafiya, comes from the native blood that traces itself to Mkisi, while Aisha’s grandfather came to Mombasa from Hadramawt in modern-day Yemen.

Hadhrami assimilation into Kenyan society came with a crucial concession, a humility, that meant, as Bajaber described it to me, they’d keep quiet, follow the laws of the country and do what was honourable. In this assimilation, they adopted local customs, ate local food and spoke Swahili. All the markers tying them were no longer in Yemen, but in Kenya. In an interview that came out just after the publication of her novel, Bajaber said,

Regardless of where the Hadhrami settled, as much as we keep our old ways, our traditions always mesh with the local traditions. The East African coast was subjected to Arabization by the Omani sovereigns, but the Arabs here were—what is the word? Swahilized? Any community that comes here ends up romanced and integrated by the strong, already-established Swahili culture. There was already a sharing of values and religion, already something in common. The Swahili culture is a poet culture, as is the Hadhrami culture. In some ways, I don’t know if any other two communities have ever suited each other better.

Yet for Aisha this marriage between two communities becomes a struggle for identity. The conflict arises less because there was a schism of tradition; rather, it is that their dalliance brings to the fore what feels to Aisha like a stricture of conservatism. When Hamza offers her the sanctuary of the House of Rust, she senses a refuge, a place to discover who she wants to be. Of course, should she choose to go into the House of Rust, she is choosing to follow the advice of a cat who may or may not be a jinn. We watu wa bara recoil in horror.

*

There were two main waves of migration from Arabia into what is now Kenya. The first, by the Omani, was more directly consequential, as they established themselves as a ruling class after the 1698 overthrow of the Portuguese in Fort Jesus, and ruled the town for the next twenty-five years. Thereafter, the Mazrui clan, originally from Oman but not loyal to Muscat, reigned over the town for a century, before the restoration of Omani rule, with a one-year break in between for the British. The second wave involved Yemeni Arabs—the Hadhrami. Unlike the Omani, who were basically rulers and gentry, the Yemeni immigrated to East Africa as labourers, traders and soldiers in search of a better life.

In the interim, there were other, smaller, waves of migration. One of these was between China and East Africa. The Dragonfly Sea concerns itself with one of these voyages. In the book, a young girl in Lamu, a town along the Kenyan Coast which, like Mombasa, was one of the city-states targeted by the Portuguese, discovers she is descended from a sailor on one of the fleets of the fourteenth century Chinese mariner Zhang He, whose expeditions brought him to East Africa. The similarities between The Dragonfly Sea and The House of Rust are patent. Both writers have an aesthetic commitment to the lushness of their language, which fosters breathless descriptions of the Indian Ocean. Both main characters, each of them Coasterian girls, are descended from a traveller to the East African coast. Both their mothers are ‘problems’ whose independence angers those around them. Both of them have fathers who are disappeared by the Ocean.

When writing The House of Rust, Bajaber made sure not to read Owuor’s novel. ‘When I was writing, I couldn’t read The Dragonfly Sea because I was scared,’ she tells me. ‘Her prose, you would be bewitched, and I know I would have been susceptible. It would have influenced how I was writing.’

Owuor is to a younger generation of Kenyan writers, especially those of us who write fiction, a beacon, a model whose writing we aspire to. Bajaber is no different. She loved Owuor’s debut, Dust. It inspired her to see what could be achieved with writing. ‘In Dust, she has such a cinematic way of writing,’ she says. ‘Like the chapter with Odidi, the chase scene. I know some people say that reading this kind of fiction is a bit difficult because you need to pay attention, but in paying attention you get drawn into it; you’re living in that world. I actually have it here.’ She reaches above her. It is the Vintage Books edition, with the orange cover, the sky above rolling purple hills. She is smiling now. She flips through the pages. ‘For example, here, page twenty-one,’ she says. She points at the page. She starts reading: ‘Outside sounds. Étude of squealing tires. Bird chirp. Machine-gun opening sequence. A scream.’

Bajaber smiles at me. ‘You can’t just write, you have to think about your approach. And the fact that she actually thought about her approach to that extent, I’m just amazed.

‘I’ve always found it interesting how she plays with structure, how she plays with pacing.’

She turns the pages. She reads sentences she loves, at random. She flips through once more. ‘When Odidi gets shot, look at how it’s structured.’ She holds up the page to the camera. ‘Can you see it? It’s like almost bullet points.’ She lowers the book. ‘I felt my heart racing during that chapter.’

Both Owuor and Bajaber are exemplars of contemporary Kenyan literary fiction, part of a chain that links back to Ngũgĩ (surely a one-namer if ever was one) and the other novelists who have defined the oeuvre over the last fifty years: Meja Mwangi, whose characters Dusman Gonzaga and Ben were our guides to Nairobi’s post-independence urban mythologies; Marjorie Oludhe Macgoye, the ghostly Paulina her appendage; David Maillu and all the sex; Margaret Ogola’s propagandist Catholicism; Charity Waciuma’s sprightly teens; all the others too numerous to name.

In October 2020, Nanjala Nyabola wrote an essay about a series of new books that pointed towards the rebirth of Nairobi’s fiction. She notes,

‘Makena Maganjo’s debut novel South B’s Finest, Billy Kahora’s short story collection The Cape Cod Bicycle War, and Nairobi Noir, a collection of crime stories edited by Peter Kimani, all published this year and last, are insightful additions to these new Nairobi narratives.’

Rightly, she praises these writers for refusing to give up on telling Nairobi stories. Over several conversations with friends, I expressed a somewhat foolish complaint: but what about non-Nairobi narratives? At the heart of my unease was the knowledge of how dominant Nairobi is in Kenyan literary tradition, even while acknowledging how endless and pointless such bickering about nano-geographical representation can get. Where were the new novels about other Kenyan locales?

Of course, one would point out that both of Owuor’s novels were for the most part not set in Nairobi, even though Dust’s Northern Kenya is a conduit for the author’s political unease about Kenya’s displaced margins, rather than being qua Northern Kenya. The release of The Dragonfly Sea brought joy; here, finally, was the Kenyan Coast brought alive in literary fiction.

This joy at representation has been amplified by The House of Rust. Bajaber told me that her writing was informed, first, by her own interests as a Coasterian, then by her interests as a Kenyan. In her shorter prose, there are hints of this decision to centre the Coast in her writing. Both ‘Gujama’, a short story published in the online literary magazine A Long House, and ‘Kiziwi’, which was published in Down River Road (also an online literary magazine), are set on the Kenyan Coast, and ‘Gujama’ features the same fantastical elements from the Coast we see in A House of Rust.

In her novel, Bajaber gives us several glimpses of her city, Mombasa. There are, of course, the goats, masterless goats, which Aisha is extolled not to be like. (‘Being masterless is supposed to be terrible?’ Aisha asks). There is the eerie spectre of the cemetery at Makaburini, where pedestrians ‘asten their step, eager to be away from it, sometimes cowed into a quick, quiet prayer’. There are the train tracks that bridge Tudor Creek, which, Zubeir tells Aisha, is the best place to hunt sharks, as they are attracted to the sparks of the trains. There are the glimpses of Sparki, where our hero lives.

But more Mombasa than all else, perhaps, are the crows.

‘In the grand green roof of Mombasa’s heart, the crows slept. Be they busying the day in Lamu, Malindi, Kwale—night flew the crows back to Mombasa like businessmen returning to their families.’

The crows sit on the beams of Marikiti, the historical former slave market turned European-and-Asians-only colonial market turned spice centre, observing the going-ons of the city. One crow, Gololi, flies over Old Town, and sees a boy enter the House of Smoke and Shadows, the so-called forbidden territories. Another crow, White Breast, finds himself under bounty, a senate of crows keen to kill him. He is advised to flee to Mecca.

In recent decades, crows, particularly the grey-breasted Indian house crow, have become ubiquitous in Mombasa. Bajaber tells me that it wasn’t the sound of crowing cocks she heard in the morning, but that of cawing crows. ‘Asubuhi, I don’t hear cockerels,’ she says. ‘I hear crows, as early as five-thirty in the morning, washaanza kupigana or to discuss whatever they are discussing.’

Encouraged by a lackadaisical approach to garbage disposal, house crows wreak havoc in Mombasa, Malindi, and other coastal towns. They are voracious predators, steal food from residents’ houses (a crow once stole money from Bajaber’s hands), hunt small reptiles and mammals, and have destroyed songbird communities, among a litany of scenes. House crows are, in these parts, considered an enemy of urban planning. Cue all the efforts to eradicate them.

Yet, to Bajaber, the birds are an important symbol of Mombasa. ‘I love the crow,’ she says. ‘When I see the crow, I feel so happy. They are a part of this community.’

*

There used to be a single, tried-and-tested path for the African writer of fiction. Write short story, submit to Caine Prize, MFA, submit to Caine Prize again, repeat last step until shortlisting, get agented, publish novel. However, the Caine Prize has paled in significance, and at the same time the proverbial path has opened up (two events that may or may not be linked), the presence of the internet playing a big part in this democratisation. Now, there are new waves of African writers whose paths to success exist largely outside the direct largesse of the Caine Prize. I am thinking of writers like Bajaber; or Eloghosa Osunde, who, though she once attended a Caine Prize workshop, has never appeared on its shortlists; or Karen Jennings; or Nana Darkoa Sekyiamah; or any number of others.

Of course, Bajaber’s journey hasn’t occurred in a vacuum. While her writing emerged at a time when the Kenyan literary scene was beginning to mourn the demise of Kwani?, she had links to other Kenyan literary platforms. Before her Graywolf Prize win, she was published in Brainstorm Kenya and Enkare Review—two departed platforms—and took part in a writing workshop organised by Jalada Africa. However, it was the Graywolf Prize for Africa, a non-Caine Prize entity, that led her to where she is.

I wonder now what role the Graywolf Press Africa Prize will have as an authenticating agent for the African writer. Its prize money is relatively insubstantial, and it lacks the razmataz that the Etisalat Prize for Literature, in its brief heyday, enjoyed as it rampaged through the continent (how many of us still remember with fondness the very emotive conflict its 2015 winner, Fiston Mwanza Mujila’s Tram 83, stoked). In her PhD dissertation, Doseline Kiguru argues that ‘in the absence of numerous literary awards on the continent, the poor publishing sector has ensured that the act of publication sometimes becomes an award in itself’. The Graywolf Prize is a double salvo, then; in the absence of both prizes and literary publishing firms in anglophone Africa, the act of publication is a prize, but the act of publication is also a Prize.

Still, there are many ways to skin a rat, and for us the very juicy rat is the global literary marketplace. Bajaber’s book is here with us, and If an Egyptian Cannot Speak English by Noor Naga, the winner of the 2019 Graywolf Press Africa Prize, was published in April this year.

I asked Bajaber what had changed for her in the wake of winning the prize. There are unexpected pleasures. Like the joy of knowing that people from Mombasa are reading her work. Some of their comments on The House of Rust reach her. ‘Sometimes they come to me through my mum. Someone’s daughter will be like, I read The House of Rust. Do you know this girl? And she’ll be like, yeah, I’m actually in the same Koran group as her mum.’

But for a person who doesn’t like revealing things about herself, the interviews and publicity have been difficult. She smiles wryly. ‘The curse of the writer. When you buy a ticket to be a writer, that’s what you get.’

- Carey Baraka is a writer from Kisumu, Kenya. His writing about literary culture, food, and politics, among other things, has appeared on Literary Hub, the Johannesburg Review of Books, Electric Literature, Serious Eats, Foreign Policy, and Gay Magazine, among other places. He sings for a secret choir in Nairobi.