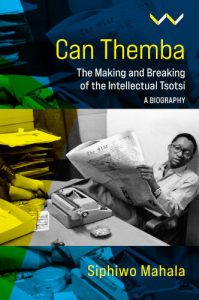

The JRB presents an excerpt from Siphiwo Mahala’s new biography, Can Themba: The Making and Breaking of the Intellectual Tsotsi.

Can Themba: The Making and Breaking of the Intellectual Tsotsi, a Biography

Siphiwo Mahala

Wits University Press, 2022

Read the excerpt:

~~~

A Quest for Shared Identities

Can Themba came to maturity and established himself as a voice to be reckoned with at the same time that apartheid was formally entrenched and extending its reach. As a fresh graduate from the University of Fort Hare, Themba effectively became part of the new black elite. His going to Johannesburg, living in Sophiatown and becoming part of the first generation of the historic ‘Drum Boys’ placed him in the precarious position of navigating the reality of his blackness in an oppressive state.

His generation added another layer to the so-called New African phenomenon, but, like the generations before them, they confronted challenges that were brought about by the realities of being black and Western-educated in a white world that did not fully welcome them, and a black world that did not fully accept them. They belonged to both communities, yet were tolerated only uneasily or reluctantly, if not downright resented. Some members of the white community, the police in particular, felt threatened by their progress in life, and made it their mission to remind them that they remained black and inferior, while members of their own black communities felt that they represented Western and modern white values that had a corrupting influence in black societies.

This is what led to the new black elite being called ‘the situations’, described by Bloke Modisane as ‘something not belonging to either’; fence-sitters who stood a chance to benefit from either side, but also ran the risk of falling onto the wrong side. Modisane goes on to describe the ‘situation’ as follows: ‘The educated African is resented equally by the blacks because he speaks English, which is one of the symbols of white supremacy, he is resentfully called the Situation, something not belonging to either, but tactfully situated between white oppression and black rebellion.’

The African intelligentsia became ‘situations’ without necessarily embracing white values or espousing the ideals of their white liberal friends. They earned the label by virtue of their perceived position ‘on the fence’ and were therefore labelled and classified as such by their own African communities, as well as elements of the white community, to which they were close by virtue of education and class.

Although there are several factors that led to this kind of categorisation, the fundamental differentiating factor was education. It was through education that ‘New Africans’ got better-paid jobs, spoke the language of the white man, and therefore could attend parties and events organised by white liberals—they could even occasionally have a taste of consensual carnal exchange across the colour bar.

In the years prior to the introduction of apartheid as an official system of governance in 1948 in South Africa, the government elevated educated Africans within their own communities. They were given special privileges, such as permission to buy bottled liquor and the relaxation of certain laws regarding official documentation. However, with the coming of grand apartheid came blanket oppression. In his essay ‘A Question of Identity’, Lewis Nkosi speaks of the levelling effect of apartheid, wherein the entire black population had to endure the effects of apartheid equally. The black intelligentsia was no longer spared, but suffered alongside the uneducated:

During the rule of the United Party, which was dominated by English-speaking white South Africans, educated Africans, mostly teachers, were exempted from the humiliation of carrying ‘passes’ or identity documents, which they would be asked to produce at street corners of the city by an official Tom, Dick and Harry. However, the subsequent Boer administrations have discarded any such discretion, and once again the life of the educated class is as insecure as those of the illiterate and semi-literate masses of our people.

Nevertheless, the social distinctions remained within communities. Since the establishment of mission stations and schools, there was a visible demarcation between educated blacks and those who were either non-literate or not educated according to Western standards. This subject is interrogated in great detail in Zakes Mda’s seminal novel, The Heart of Redness, where the Xhosa people are divided according to the binary of ‘Believers’ and ‘Unbelievers’. In this hierarchy, educated blacks occupied the upper echelons of black society, even though they remained lower than the lowest white. One result was class hostility within the black population. It was in this context that the black intelligentsia were resented by sections of both black and white communities.

The view that they were ‘Black Englishmen’ was perpetuated by the perception that they aspired to emulate the life of whites by befriending them and attending their parties. In his paper ‘Can Themba, Storyteller and Journalist of the 1950s’, Michael Chapman expands on this:

They were over-enamoured with the fads of Western culture, they were regarded as curiosities by a paternalistic white-liberal intelligentsia, and were isolated from any purposeful mass-based activity. Accordingly, Themba’s own substance and style are … denuded of experiential necessity and seen as ideologically ‘unhealthy.’ As the u-Clever of Sophiatown, who claimed to speak no African language, and whose education in English Literature at Fort Hare had seemed to manifest itself in the frustration of his writing tales of intrigue, violence and wish fulfilment, Themba is typified as an alienated ‘situation.’

One can argue that this generation of African intelligentsia lived a dual lifestyle: one that related to their people in the townships, and another that was suitable for their white liberal friends.

So, on the one hand, Themba was a journalist famed for his ability to capture in words the heartbeat of township life, a connoisseur of shebeens, a man who dodged the police and provided poetry to tsotsis. At the same time, he and his peers, including Modisane, Nakasa, Nkosi and others, would attend social gatherings organised by progressive whites such as Nadine Gordimer and Helen Suzman.

In her biography of Nat Nakasa, author Ryan Brown tells the story of how Nakasa, while attending a party organised by Francie Suzman (daughter of anti-apartheid MP Helen Suzman), gave himself a tour of the house. Later, Nkosi found him sleeping in the main bedroom. When Nkosi asked his friend for an explanation, Nakasa’s response was that he wanted to see how the other half lived. This statement shows that even when cultural figures such as Nakasa immersed themselves in the lifestyles of white liberals, they remained acutely aware of their differences and critical of the system and the roles, deliberate or not, of their white counterparts, even as they attempted to build bridges between races.

Their criticisms came at different stages of their personal journeys and in different forms. Jean Hart claimed that Can ‘kept the real, objective complexities in front of him, as a kind of barrier, because that was one way of being honest with himself’. It may be argued that Themba’s outspokenness about matters of race was his way of coping with the status quo. Hart went on: ‘Can … would say [it] outright. He would say, You and I can never be real lovers, you and I can never be real friends, because our power-base is unequal. Bloke would avoid it and say, We love one another, there’s nothing society can do to us.’

Bloke Modisane, who in his book Blame Me on History appears to be bitter about his own social collusion, initially appeared to be docile, almost naive concerning the racial dynamics of his time. Jean Hart felt that Modisane was insincere; that he tried to suppress his opinions for the sake of belonging. In his autobiography, Modisane confirmed these assertions; he confessed to having done things to impress or spite his supposed detractors. In his book, he tells the story of how he bought some Russian caviar at an exorbitant price, simply for the sake of ensuring that he was not thought of as an unsophisticated and uncivilised African. The worst was that he did not particularly like caviar, but his act of buying what he confessed to be a pretentious luxury was ‘a bourgeois symbol of social affectation and palatal sophistication’. Modisane’s bitterness reveals him to be probably the angriest among his peers. He does not seem to have enjoyed the parties to which he was invited: ‘I am instead insulted with multiracial tea parties where we wear our different racial masks and become synthetically polite to each other, in a kind of masquerade where Africans are being educated into an acceptance of their inferior position.’

Themba, his remarkable ability to straddle the fault lines between social strata notwithstanding, had no such issues with making his true feelings and opinions known. As Hart pointed out above, he could be blunt, even harsh, in acknowledging the reality of racial differences in a racist society. Tom Hopkinson was also on the receiving end of Themba’s frank views on identity politics. In one of their engagements, which bordered on confrontation, Themba put Hopkinson in a corner, trying to force him to be unequivocal about the side he would take in a racial war rather than assume the nebulous stance often taken by white liberals—which Themba found patronising. Hopkinson reports that Themba asked:

‘When the shooting war starts—which side will you be on then, black or white? Because one day the whites will start it for sure.’

I made no answer, but Can pressed. ‘Which side will you be on?’

‘Depends on who starts it, what the issues are, and where I’m standing at the time.’

Can snorted and went out. Our talk had been unsatisfactory to him as it had to me.

As well as the clarity of his views, this reveals Themba’s appetite for debate. He was willing to tackle anyone. In his short story ‘Crepuscule’, Can Themba, the narrator, who is also a character in the story, presents his case to the tsotsis of Sophiatown after they side with his erstwhile girlfriend, Baby, who reported him to the police for having an affair with another woman—who happened to be white. The tsotsis initially side with Baby, but change their minds after Can explains that going out with a white woman is in fact a revolutionary act of retaliation by a black man—unlike others who freely procured their black sisters for white men.

His capacity to relate to everyone and anyone is eloquently articulated by Musi: ‘Can could talk to a professor in the morning, a beauty queen at lunch-time and a gangster in the afternoon. And have everyone laughing and eating out of his hand.’ This illustrates that while every individual possesses multiple identities, Themba’s identity ethos was particularly sophisticated and flexible. Where we are fortunate in trying to trace the construction of Themba’s identity is the time and context in which he lived, in which he and peers like Modisane and Nakasa deliberately analysed and reflected on their situation in their historical moment. Even more useful, they wrote about each other, giving opinions and insights about themselves and their peers.

In Blame Me on History, for instance, Modisane refers to both Themba and Nakasa; likewise, Nakasa talks about his relationship with Themba in a number of published pieces. It is perhaps in Themba’s tribute to Nat Nakasa, ‘The Boy with the Tennis Racket’, that we get the most intimate glimpse of the author’s sincere views about his contemporaries:

The bitterest commentary on the South African is typified by Nat. All those South Africans who wanted to be loyal, hard-working, intelligent citizens of the country are crowded out. They don’t want to bleach themselves, but they want to participate and contribute to the wonder that that country can become. They don’t want to be fossilised into tribal inventions that are no more real to them than they would be to their forefathers.

Nat’s was such a voice. Sobukwe’s is that of protest and resistance. Casey Motsisi’s that of derisive laughter. Bloke Modisane’s that of implacable hatred. Ezekiel Mphahlele’s that of intellectual contempt. Nimrod Mkele’s that of patient explanation to be patient. Mine, that of self-corrosive cynicism. But Nat told us: ‘There must be humans on the other side of the fence; it’s only we haven’t learned how to talk.’

The above excerpt does more than provide snapshots of the various individual characters; it also gives context and clarity to their identity journeys. When Themba wrote this piece after the passing of Nakasa in 1965, he was exiled in Swaziland, just as Nakasa had been exiled in the United States. One might have expected his piece to be filled with anger and frustration, given that, like him, Nakasa had been forced to leave the land of his birth. Instead, Themba’s piece is a nostalgic one that journeys down memory lane, recapturing his first encounter with Nat and reflecting on their lives in Sophiatown. The first paragraph cited alludes to their refusal to be reduced to tribal subjects, while simultaneously rejecting the idea of being turned into white (‘bleached’) subjects. While they believed in and shared the broad quest for identities beyond tribal and ethnic confines, on an individual level their differences were notable. These differences have been astutely and concisely captured by Themba, who, in this excerpt, lists prominent black South African intellectuals who shared common backgrounds and yet differed widely ideologically.

- Siphiwo Mahala is an award-winning novelist and short story writer, playwright and literary critic. He is a senior lecturer in the Department of English at the University of Johannesburg and a research fellow at the Johannesburg Institute for Advanced Study. He is the editor of Imbiza Journal for African Writing.

~~~

Publisher information

An engaging read, well-researched and accessible. It offers new insights not only on Can Themba—the subject of the book—but on his era, his peers, and the movement that later became known as the Sophiatown Renaissance. Mahala captures the period and its politics so vividly that he makes the reader critically aware of how it felt to be in those events, rather than merely chronicling them.

—Professor Zakes Mda, novelist, poet and playwright, Professor Emeritus of English, Ohio University and Creative Writing Lecturer, Johns Hopkins University.A satisfying chemistry radiates from every page of Siphiwo Mahala’s biography of Can Themba. Mahala’s clarity, vivid narration, and fi rm touch do full justice to the life and work of Themba, a brilliant artist who was mercurial and troubled in equal measure. The result is an affectionate and astute biography that reaches across the generations.

—Professor David Attwell, author and Professor of English, University of York and Extraordinary Professor, University of the Western Cape.

This rich and absorbing biography of Can Themba, iconic Drum-era journalist and writer, is the definitive history of a larger-than-life man who died too young. Siphiwo Mahala’s intensive and often fresh research features unprecedented archival access and interviews with Themba’s surviving colleagues and family.

Mahala’s biography takes a critical historical approach to Themba’s life and writing, giving a picture of the whole man, from his early beginnings in Marabastad to his sombre end in exile in Swaziland. The better-known elements of his life—his political views, passion for teaching and mentoring, and family life – are woven together with an examination of his literary influences and the impact of his own writing (especially his famous short story ‘The Suit’) on modern African writers in turn. Mahala, a master storyteller, deftly follows the threads of Themba’s dynamic life, showcasing his intellectual acumen, scholarly aptitude and wit, along with his flaws, contradictions and heartbreaks, against a backdrop of the sparkle and pathos of Sophiatown of the nineteen-fifties.

Can Themba’s successes and failures as well as his triumphs and tribulations reverberate on the pages of this long-awaited biography. The result is an authoritative and entertaining account of an often misunderstood figure in South Africa’s literary canon.