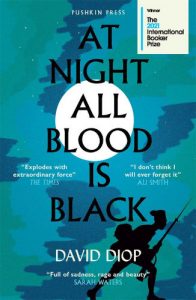

The JRB presents an excerpt from At Night All Blood Is Black, recent winner of the International Booker Prize.

At Night All Blood Is Black

David Diop (translated by Anna Moschovakis)

Pushkin Press, 2020

Read the excerpt:

My trench-mates, my war brothers, began to fear me after the fourth hand. At first, they laughed with me heartily, they enjoyed watching me come home with a rifle and an enemy hand. They were so pleased with me, they even thought of giving me another medal. But after the fourth enemy hand, they no longer laughed so easily. The white soldiers were beginning to say—I could read it in their eyes—‘This Chocolat is really strange.’ The others, Chocolat soldiers from West Africa like me, began to say—and I also read it in their eyes—‘This Alfa Ndiaye from the village of Gandiol near Saint-Louis in Senegal is strange. When did he become so strange?’

The Toubabs and the Chocolats, as the captain called them, continued to slap me on the shoulder, but their laughter and their smiles had changed. They began to be very, very, very afraid of me. They began to whisper, right after the fourth enemy hand.

For the first three hands I was a legend, they cheered me when I returned, they fed me delicacies, offered me tobacco, helped me rinse off with big buckets of water, helped me clean my uniform. I saw in their eyes that they understood. I was performing, in their place, the grotesque savage, the enlisted savage obeying orders. The enemy on the other side should be trembling in his boots and under his helmet.

In the beginning, my war brothers weren’t bothered by my stench of death, the stench of a butcher of human flesh, but beginning with the fourth hand they avoided smelling me. They continued to give me delicacies, to offer me bits of tobacco they’d collected from here or there, to lend me a blanket to warm myself, but with a fake smile plastered on their terrified soldiers’ faces. They no longer helped me rinse myself with big buckets. They let me clean my uniform myself. Suddenly, nobody was slapping me on the shoulder and laughing. God’s truth, I became untouchable.

So they set aside a bowl, a cup, a fork, and a spoon for me that they kept in a corner of our dugout. When I came home very late at night on battle days, long after the others, never mind the wind, rain, or snow, as the captain said, the cook would tell me to go get my things. When he served me soup, he was very, very careful that his ladle not touch the interior, the sides, or the rim of my bowl.

The rumor spread. It spread, and as it spread it shed its clothes and, eventually, its shame. Well dressed at the beginning, well appointed at the beginning, well outfitted, well medaled, the brazen rumor ended up with her legs spread, her ass in the air. I didn’t notice it right away, I didn’t recognize the change, I didn’t know what she was plotting. Everyone had seen her but no one described her to me. I finally caught wind of the whispers and learned that my strangeness had been transformed into madness, and madness into witchcraft. Soldier sorcerer.

Don’t tell me that we don’t need madness on the battlefield. God’s truth, the mad fear nothing. The others, white or black, play at being mad, perform madness so that they can calmly throw themselves in front of the bullets of the enemy on the other side. It allows them to run straight at death without being too afraid. You’d have to be mad to obey Captain Armand when he whistles for the attack, knowing there’s almost no chance you’ll come home alive. God’s truth, you’d have to be crazy to drag yourself screaming out of the belly of the earth. The bullets from the enemy on the other side, the giant seeds falling from the metallic sky, they aren’t afraid of screams, they aren’t afraid to pass through heads, flesh, to break bones and to sever lives. Temporary madness makes it possible to forget the truth about bullets. Temporary madness, in war, is bravery’s sister.

But when you seem crazy all the time, continuously, without stopping, that’s when you make people afraid, even your war brothers. And that’s when you stop being the brave one, the death-defier, and become instead the true friend of death, its accomplice, its more-than-brother.

~~~

- David Diop was born in Paris in 1966 and grew up in Senegal. He now lives in France, where he is a professor of eighteenth-century literature at the University of Pau. At Night All Blood is Black is his second novel. It was shortlisted for ten major prizes in France and won the Prix Goncourt des Lycéens as well as the Swiss Prix Ahmadou Korouma. It is currently being translated into thirteen languages and has already won the Strega European Prize in Italy and the Europese Literatuurprijs in the Netherlands.

Publisher information

‘So incantatory and visceral I don’t think I’ll ever forget it.’—Ali Smith, Guardian Book of the Year

‘This slight book explodes with extraordinary force—readers will not forget it in a hurry.’—Antonia Senior, The Times, Historical Fiction Book of the Month & Year

‘An extraordinary novel, full of sadness, rage and beauty.’—Sarah Waters

Alfa and Mademba are two of the many Senegalese soldiers fighting in the Great War. Together they climb dutifully out of their trenches to attack France’s German enemies whenever the whistle blows, until Mademba is wounded, and dies in a shell hole with his belly torn open.

Without his more-than-brother, Alfa is alone and lost amidst the savagery of the conflict. He devotes himself to the war, to violence and death, but soon begins to frighten even his own comrades in arms. How far will Alfa go to make amends to his dead friend?

At Night All Blood is Black is a hypnotic, heartbreaking rendering of a mind hurtling towards madness.