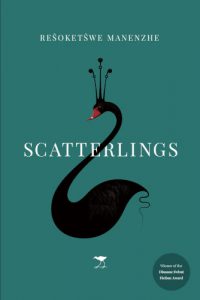

Wamuwi Mbao reviews Rešoketšwe Manenzhe’s novel Scatterlings, winner of the 2020 Dinaane Debut Fiction Award.

Scatterlings

Rešoketšwe Manenzhe

Jacana Media, 2020

There are moments of unexpected fineness in Rešoketšwe Manenzhe’s quietly poetic debut novel, Scatterlings. Here is ‘a sunless day filled with many omens’. Here is a girl interrupted in a library, ‘startled out of her busy oblivion’. Looking out on this day is a man who ‘in an upward trajectory of tragedy, or glory’, has distinguished himself in the theatre of war, but is unaware of his walk-on role as fate’s messenger.

Many debut novels—those that have not been faceted and polished by avaricious publishers—are rough gems whose surfaces only occasionally glint at their author’s future lustre. They spill over with amateur gaffes and dangling plot strands and errant pacing and wobbly dialogue, all of which have you searching the front matter for editors to blackball.

Not so with Scatterlings. It is a short but well-written historical novel that manages to not be too pleased with its own project. Pulling off a historical novel is no mean feat. There are many aspirants and precious few achievers wishing to emulate the success of Hilary Mantel. Such novels are often in thrall to size, as though to convince the reader that heft equals worthiness. Much historical fiction leaves me cold for this very reason: the idea of wading through a wearisomely large book of relentlessly recondite detail and painstakingly fettled historical pedantry is like being presented with a sandwich where either the bread or the filling is supplied in excess. Manenzhe does well to compact a twentieth-century historical tragedy into 213 pages of supple prose that draws the reader into the sulphurous white nationalist mood that choked South Africa between the wars.

The tragedy in question is the passing of the 1927 Immorality Act, a malodorous statute which typified the Nazi-understudy South African government’s abiding fascination with who people rubbed offal with in their private hours. Scatterlings begins with the news of the act being passed. Alisa and Abram van Zijl are a couple with two young daughters, Dido and Emilia. Their lives are comfortable—a manor house and farm in the Constantia Valley with staff and a chauffeured car—and sheltered, but disaster colours the horizon. Alisa is black, and the two girls are evidence of their involvement in a union that has been criminalised by the state.

A sinister functionary of the state appears at the margins, asking questions at the girls’ school, showing up unannounced, his politeness menacing as he peers into their private world. Abram is at a loss as to how to protect his young family from the grinding machinery of the law, whose worst discriminations have until now been kept at bay by the family’s economic privilege. The couple’s bond is tattered, and the disinterested finality of the new legislation severs the last threads that tie them together.

But the passing of the law is not the first act in the tragedy. As Alisa ruefully puts it, ‘Some stories start in the middle because no one wants to hear the beginning.’ The reader is left to see where the beginning might be, to where the Van Zijls became trapped in the wreckage of a collapsing world. Like early Cormac McCarthy, Manenzhe’s characters are tangled in the lines well before they learn the awful truth of their peril.

This is not a sentimental two-against-the-world love story. On the contrary, it is an affecting portrait of grief and unrelenting despair in the face of impossible circumstances. Alisa, who is Jamaican and the descendant of slaves, is adopted by a wealthy white British couple, who raise her as their child. But as she grows older and realises that the prejudices of British society make no allowance for her, she longs to find sanctuary in the world, and so she journeys to a South Africa that is just beginning to shape itself into a modern nation. Her meeting with Abram aboard the liner that transports them will, it turns out, be a fateful one. Alisa’s descent into depression is catalysed by the encroaching public mood, a gathering storm her husband chooses to ignore until it is too late.

What follows is a wrenching act of desperation that irrevocably changes the lives of the Van Zijls. Alisa unseats herself from the world, taking Emilia with her in a moment of necessity and cruelty that approaches the blood-soaked desperation of Beloved’s Sethe. Her actions force an unbearable reckoning for her husband, who must flee with the eldest daughter (Dido wakes in time to escape), not knowing where quarter will be granted. But Manenzhe defers the expected lurch into a hunt-and-seek fugitive story. It becomes, rather, an unconventionally conventional Orphic journey, in which Abram tries to reconnect with his wife in order to understand what drove her to her actions.

His shadow on this journey is his surviving daughter. Dido is of course a shadow of her mother (there is no need for a tedious retelling of the Aeneid here), and her thoughtful presence in the story allows those around her to reflect on the sorts of things adults in fiction always draw from children. The novel illuminates her guarded inner world. And if the precocious Dido is not especially believable as a child, she is nevertheless her parents’ scion, possessed of their entangled intrigues and sadness, and aware of how she is scrutinised by the outside world:

She had skin darker than her father’s and eyes as brown as her mother’s. And although her hair was long and loosely curled, she realised that people assumed this was a result of some unspeakable secret tragedy.

Scatterlings does well to keep the focus on its small band of characters. It is a novel about their fragile interiorities, not a novel about the Immorality Act. Abram, who seeks refuge in the dying embers of an old friendship, and Dido, who seeks out the love her mother has only briefly enjoyed, are flung together by circumstances that do not promise to abate. They beat on, their family a shared boat against the inexorable current of what is to come.

The back-catalogue of novels concerned with South Africa’s miscegenation laws is well populated, and they invariably harden around a key idea: that what apartheid trampled in its malevolent self-regard is the possibility and potentiality of privacy, Black privacy particularly. In this regard, apartheid echoed fascism everywhere else. Think of Robert Ley, the Nazi politician whose triumphalist boast was that in Nazi Germany there were no private individuals. To move about in an unkind world under the mark of racial blackness, as Alisa does, is to have control of public and private wrested from one, be vulnerable to surveillance and intrusion, and to be always threatened with displacement. We read this, ironically, most closely in a series of diary fragments her husband recovers, which form the middle scenes of the story. Alisa’s fear of rootlessness is a gnawing anxiety that is sensitively realised by Manenzhe’s writing. It draws fine comparison with Morrison’s The Bluest Eye, where she describes a similar exposure as ‘the end of something, an irrevocable, physical fact, defining and complementing our metaphysical condition’.

For a historical novel to read successfully, it isn’t enough simply to create a salmagundi of historical event and fictional artifice. The best of the genre are those books that invent a compelling alternative reality. Scatterlings is an intriguing read because it doesn’t feel as though it’s dutifully checking in at historical stations along the way. Nobody comes along to parade facts about the times. Where many historical novels abdicate their scaffolding to historical information, the story of the Van Zijls anchors itself to feeling. The result is a story whose emotional register is expansive and patient. We understand that Alisa’s story refuses to be summarised. Instead, it invites the reader to contemplate the unseen depths of her life: how it is formed and shaped by the torsions of racial discrimination, and what the resulting loneliness might look like if we could begin to perceive it from the inside.

The book is not perfect. Like many first novels, the plot begins to chunter and struggle to maintain its initial vitality. The title comes from a Johnny Clegg song, which will delight white South Africans of a certain age, but is artlessly tied to the actual events of the novel: a watery title is always a mistake, even more so when the novel it nameplates is convincing enough to deserve better. And some finetuning might have reduced one or two of the discordant clunks that jar the reading:

The Act has been passed, hasn’t it?

Abram nodded. Alisa slid back to the ground. She settled on her knees and tears quickly sprung into her eyes. Abram slid, too, to his knees, and held her hands.

Read that moment out aloud and see where the language stumbles. Reading this book is often a matter of leaping over the flaws to get to the lovely moments where the author sees the world as closely as the characters might. Dido chasing embers through a vineyard is an image that will stay with me, and its crafting bears the mark of a talented writer.

Scatterlings leans into a sad time, and what it finds there does much to cut a swathe through a genre—South African historical fiction—that overflows with men’s stories. The novel brings texture to a story that is more faded and more illegible than other moments in our shared history. It may be too sad for the telling, but the attempt is a worthy one.

- Wamuwi Mbao is an essayist, cultural critic and academic at Stellenbosch University. Follow him on Twitter.

This is really frustrating: I’m interested in this book, and have tried Fishpond, Amazon, the Book Depository and Zoot and they all say the book is not available.

So it that because it’s already been published and has sold out, or has it not been released yet?

It would be helpful to international readers if the JRB could include, as a matter of routine, the ISBN and other publishing details such as whether it’s available as an eBook.

Correction: “is that because” not “It that because”.

(I’m bad at proofreading my own writing).