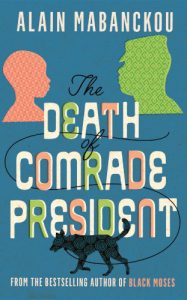

The JRB presents an exclusive excerpt from The Death of Comrade President, the new novel from Alain Mabanckou.

The Death of Comrade President

Alain Mabanckou (translated from the French by Helen Stevenson)

Allen and Unwin, 2020

Read the excerpt:

~~~

The talking tree

That’s the third time Maman Pauline’s asked us to switch off the radio because it’s time to sit down to eat. She says it’s not good to eat while you’re listening to Soviet music, you won’t appreciate the flavour of the food. Also, if you’re at table it’s better not to know what’s going on in the world, that way if you hear bad news it will be too late, you’ll already have eaten and belched.

My father and I don’t budge, even though Maman Pauline’s calling, we stay put under the old mango tree, which is one of our three fruit trees, along with the papaya and the orange tree outside the kitchen. Maman Pauline planted this tree when she bought the land; she likes to tell you how she brought the seed directly from her native village, because the best mango trees in the whole country grow there, and not in Pointe-Noire, where the mangoes look beautiful on the outside but are rotten on the inside. Besides, the mangoes from here are not as sweet as the ones from Louboulou, even the flies know that, they leave them alone.

This tree is a kind of second school for me, and sometimes my father jokingly calls it the ‘talking tree’. This is where he always comes to listen to the radio when he gets home from the Victory Palace Hotel. His work is very tiring, so at the weekends he rests here, from morning till sundown, just sitting in his cane chair, with the radio right up close. He could go and lie in his bed and take it easy, but the trouble is, the aerial doesn’t really work inside the house, it’s like you can hear the sound of popcorn bursting in boiling oil coming from inside the Grundig. Also, it’s often just when the news is really important that the voices get all jumbled up and in the end the transistor tells stories that are just not true. A radio should never lie, especially if it was really expensive, and the batteries are still new, because my father sends me to buy them at Nanga Def’s, the West African seller with a shop two minutes on foot from Ma Moubobi’s.

I’m serious about this thing with a school under the mango tree. For example, this is where my father told me lots of secrets about the war in Biafra, because the Voice of the Congolese Revolution was always talking about it. Our radio informed us that Olusegun Obasanjo, the President of Nigeria, where the war took place, had been congratulated that year by Pope Paul VI for organising a huge meeting of blacks from all over the world. Our journalists, who wanted to be in the good books of the government and Comrade President Marien Ngouabi, started off saying it was a scandal, shouldn’t they be congratulating our leader of the Revolution, who’d been working 24/7 to develop our country? They criticised President Olusegun Obasanjo, saying he never wore a collar and tie, he never smiled, he was a disgrace to our continent, and anyway, their war in Biafra was just a war between prostitutes about who was in charge of the streets in Lagos.

‘Michel,’ my father said, ‘don’t listen to them! Over two million people have died in two and a half years in this war!’ Papa Roger added that the Nigerians were all killing each other in a real civil war, because some people had decided they were going to create their own separate country, the Biafran Republic, alongside the normal country, even though this one had been clearly drawn up by the whites in geography books. Again according to Papa Roger, the government of Nigeria was opposed to splitting up the territory because otherwise people would wake up the next day with two enemy countries at war all day long. The government had closed the borders. But if you close the borders with a great big padlock, if people can’t come and go as they please any more, how do you get food in? Which is how famine came to Nigeria, with not a single bunch of bananas left to feed people’s hunger. Papa Roger had told me quietly—because it was an important secret that he’d heard from the whites at the Victory Palace Hotel—that the French had joined in the war, even though they didn’t even colonise Nigeria like they did us. Their president back then, General de Gaulle, had sent a man they called the ‘white sorcerer’. This man, whose real name I’ve now forgotten, was someone who never said very much, and who knows so many secrets about our continent that you wonder who the traitors were who gave him the information and how much he paid them for it. Most black presidents have to talk with the ‘white sorcerer’ to keep France happy. This is the man who decides who will be the president of the Republic of such and such a country that the French have colonised. And if one of these presidents that the French have put in power criticises the French too loudly at the UN, where they sort out rows between countries that are cross with each other, ‘the white sorcerer’ gets annoyed and the next day the jumped-up African is no longer president of the Republic, he’ll be put in jail, if they haven’t already killed him in a coup d’état secretly cooked up in France with other Africans who don’t understand they’re providing a rod for their own backs and continue to have their riches stolen at midnight when people are in bed dreaming about more important things than oil, which is the cause of so many of our problems.

‘So what I’m saying, Michel, is that France has poured a lot of money into this civil war. Both sides in the conflict, the official government and those in favour of dividing the country, asked France for help. And the French chose to support the divisionists and their Biafran Republic. Does that seem right to you?’

Since he’d told me that the French were happy for Nigeria to be split in two, I said to Papa Roger that it was wrong for one country to get involved in another country’s fights—if people get into fights and I don’t know why they’re beating each other up I just walk straight on by and don’t look back; I’m only going to fight if I’m provoked or if there’s no escape because there’s no short cut or the people after me have already caught up with me.

Papa Roger smiled and replied that since the French supported the creation of the Republic of Biafra-next-door, they’d employed mercenaries, who are bandits that get paid to cause turmoil in a country they don’t even know. One of these mercenaries—this is a name I do remember—was Bob Denard. He’s a real specialist in turmoil; before he popped up in the mess in Nigeria he’d been stirring up trouble for the people in Algeria, who were fighting to get their country back from the French. So this Bob Denard’s name in French is actually Robert, but Bob sounds scarier for a mercenary. Anyway, Papa Roger didn’t like this guy having the name ‘Robert’ because, he said, the little brother of some American president was also called Robert, although the American Robert had not been making trouble for the people bravely fighting in Algeria to get their country back from the French. When Papa Roger showed me a photo of the American Robert in the newspaper I was shocked: he was young and handsome. But even though he was young and handsome, the Americans assassinated him when he too could have become president of the United States like his big brother, who’d been shot in a car next to his wife, like in a film.

‘Michel, you’re dreaming again!’

Papa Roger gives me a shove with his elbow and interrupts me just as I’m sitting happily there under the mango tree with him, thinking my thoughts. He gives a nod and I turn round: Maman Pauline’s heading towards us, like an enraged bull.

‘Do I have to tell you twenty times to come and eat, instead of sitting around listening to lousy music? Well, you can just eat the radio today! Bon appétit!’

I don’t want to eat the Grundig or the Soviet music inside it. I want to eat what she’s prepared, especially as she announced yesterday that she was going to cook something special for me because she was proud of the good marks I’d got in my second term at middle school.

Papa Roger tries to calm her down.

‘We’re coming, Pauline, just give us a few more seconds …’

She zooms back into the house. First we hear the sound of her opening the old cupboard, then of plates smashing on the floor.

‘What on earth is your mother doing?’ Papa Roger says.

‘I think she’s punishing the plates instead of punishing us …’

~~~

About the book

A poignant tale of family and revolution in postcolonial Africa, from one of the continent’s greatest living novelists.

In Pointe-Noire, in the small neighbourhood of Voungou, on the family plot where young Michel lives with Maman Pauline and Papa Roger, life goes on. But Michel’s everyday cares—lost grocery money, the whims of his parents’ moods, their neighbours’ squabbling, his endless daydreaming—are soon swept away by the wind of history. In March 1977, just before the arrival of the short rainy season, Comrade President Marien Ngouabi is brutally murdered in Brazzaville, and not even naive Michel can remain untouched.

Starting as a tender, wry portrait of an ordinary Congolese family, Alain Mabanckou quickly expands the scope of his story into a powerful examination of colonialism, decolonisation and dead ends of the African continent. At a stroke Michel learns the realities of life—and how much must change for everything to stay the same.

About the author

Alain Mabanckou was born in 1966 in Congo and currently lives in Los Angeles, where he teaches literature at UCLA. His previous novels, in English, include Black Moses, The Lights of Pointe-Noire, Tomorrow I’ll Be Twenty, Black Bazaar, Memoirs of a Porcupine, Broken Glass, African Psycho and Blue White Red. Among his many honours are the Academie Francaise’s Grand Prix de literature and the 2016 French Voices Award for The Lights of Pointe-Noire. Mabanckou is a Chevalier of the Legion d’honneur, was a finalist for the 2015 Man Booker International Prize and has featured on Vanity Fair’s list of France’s fifty most influential people.