Adekeye Adebajo addresses the once-unthinkable question ‘Was Gandhi a racist?’, as the 150th anniversary of his birth is celebrated.

1. Gandhi at 150

On 2 October 2019, millions of Indians—and indeed much of the world—marked Mohandas Gandhi’s 150th birthday. The Mahatma (the ‘great Soul’) lived in South Africa for twenty-one years between 1893 and 1914, and honed much of his satyagraha—soul force—philosophy, including its iconic passive-resistance methods and anti-imperial tenets, on the African continent. He is widely considered to be among the greatest moral figures of the bloody twentieth century. His contributions to India’s independence struggle ensured that the sun eventually set on the British Empire, which, by 1960, catalysed the decolonisation of forty Asian and African countries with a combined population of 800 million, a quarter of the world’s population at the time. Gandhi thus helped transform international society from a Western-dominated system of ‘global apartheid’ to a more diverse one in which the ‘wretched of the earth’ now had a voice.

The Indian National Congress’s struggles against colonialism were spurred by Gandhi’s return to the sub-continent from South Africa in 1914, and inspired many West African nationalists, including Ghana’s JE Casely Hayford and Kwame Nkrumah, and Nigeria’s Obafemi Awolowo and HO Davies. The Mahatma had correctly, but somewhat patronisingly, predicted in 1924 that if Africans ‘caught the spirit of the Indian movement, their progress must be rapid’. He had also opined in 1936 that it was ‘maybe through the Negroes that the unadulterated message of non-violence will be delivered to the world’—a prophesy that Dr Martin Luther King, Jr largely fulfilled through his leadership of America’s Civil Rights struggle. Gandhi’s beliefs were to inspire seven Africans and Americans who won the Nobel Peace Prize: Ralph Bunche, Albert Lutuli, the aforementioned Dr King, Anwar Sadat, Desmond Tutu, Nelson Mandela and Barack Obama. Kenneth Kaunda and Julius Nyerere were also champions of Gandhi’s approach, though both eventually embraced armed struggle (as did Mandela, before changing tack towards the end of his imprisonment on Robben Island).

A recurring question remains, however: how much were all these admirers aware of Gandhi’s hatred towards black South Africans? Did they not know, or did they choose to ignore his deep prejudice to focus on the more positive aspects of the Mahatma’s anti-colonialism in India? Gandhi’s legacy has only recently come under much closer scrutiny. With the Mahatma’s statue having been removed from the University of Ghana’s campus in 2018, the once unthinkable question has been increasingly asked: ‘Was Gandhi a racist?’

In this essay, I address this question by focusing on Gandhi’s collaboration with British imperialism in South Africa; his parochially Indian social struggles; his avowed prejudice towards black South Africans; and his support of social segregation between blacks and Indians. We then assess the fall of Gandhi’s statue at the University of Ghana, and more recent perspectives of his legacy, which have sought to move away from his quasi-deification after martyrdom by an assassin’s bullet in January 1948. We conclude by comparing Gandhi’s legacy to that of the arch-imperialist, Cecil John Rhodes.

2. British Collusion

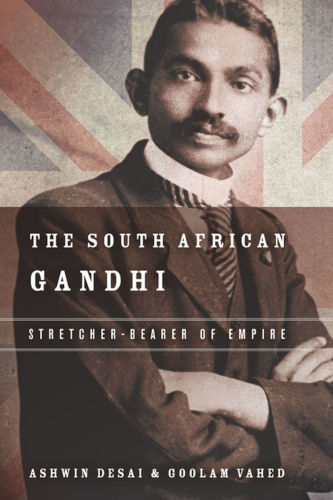

A 2015 book by two Indian South African scholars, Ashwin Desai and Goolam Vahed, The South African Gandhi: Stretcher-Bearer of Empire (Stanford University Press) provided incontrovertible evidence of Gandhi’s collaboration with the British Empire, as well as his disdain for South Africa’s majority black population. During the Anglo-Boer War of 1899–1902, determined to prove himself a loyal subject of the British Raj, Gandhi mobilised Indian stretcher-bearers as an Ambulance Corps to assist wounded British troops.

British imperialists were determined to transform the Natal Colony into a typical albinocracy that privileged the rights of white settlers over the black majority and Indian migrants, amid fears of ‘black savages’ and the ‘Asiatic Menace’. Gandhi believed strongly in the equality—intellectually, culturally and politically—of Indians with whites, and the superiority of Indians over blacks, whose cultures he detested and consistently disparaged in the most racist terms. He was an Orientalist—one of those anthropological creatures criticised by Edward Said for viewing the East through Western prisms and prejudices. As Gandhi put it in December 1893: ‘I venture to point out that both the English and the Indians spring from a common stock, called the Indo-Aryan’.

When the Zulus launched a rebellion in 1906 to resist British annexation of their lands and the destruction of their livelihoods, Gandhi once again mobilised Indians to support the imperial war effort, acting as a stretcher-bearer for the British against the oppressed blacks. About 3,500 Zulus were killed and 30,000 rendered homeless during the rebellion. When World War I broke out in 1914, Gandhi again took up his stretcher on behalf of the British Empire. Rather incredibly, the man known as the twentieth century’s greatest apostle of non-violence offered to defend the British Empire again in 1918, urging ‘full assistance’ to the effort to overthrow the Germans.

3. Parochially Indian Struggles

During his twenty-one-year sojourn in South Africa, Gandhi fought parochially Indian battles, and ignored the rights of the black majority, whom he never viewed as equals or potential partners. The anglophile Gandhi was happy to live under the British crown as a loyal subject, and regarded the imperial power as the salvation of Indians. It was only after his demands for equal rights were ignored by British mandarins that he took up the struggle for South African Indians. He fought—at the behest of Indian merchants—to restore the Indian franchise in Natal in 1894, employing non-violent resistance methods that involved provoking arrest and gracefully accepting punishment.

Gandhi started his passive resistance demonstrations after the 1906 ‘Black Act’ was passed in the Transvaal Colony, which required Indians to be fingerprinted. He still naively believed that the British would grant equal rights to Indians. The Union of South Africa in 1910—in which the British and defeated Boers effectively shared out the land and its bounty, while marginalising the black majority, Indians and ‘Coloureds’—once again confirmed the treachery of ‘perfidious Albion’.

As African American scholar Ọbádélé Kambon has noted, Gandhi later tried to whitewash his collaboration with British imperialism, his racism towards the black majority and his parochially Indian struggles, claiming, for example that he was helping wounded Zulus—instead of injured British troops—during the brutal wars of dispossession in Natal. His two autobiographies, The Story of My Experiments with Truth (1927) and Satyagraha in South Africa (1928), can be said, through their demonstration of selective memory on these issues, to be rewrites of history.

4. Kaffir-bashing

Gandhi regularly engaged in what can only be described as vituperative ‘Kaffir-bashing’. In September 1896, he revealed how deep his racism towards blacks was, complaining—deploying shockingly crude stereotypes—that whites in Natal wished to ‘degrade us to the level of the raw Kaffir whose occupation is hunting, and whose sole ambition is to collect a certain number of cattle to buy a wife with and then, pass his life in indolence and nakedness’. Gandhi thus championed the colonial trope of the ‘lazy and happy native’. The end of this quote about black nudity was ironic, considering that the British prime minister, Winston Churchill, would later notoriously dismiss Gandhi as a ‘half-naked fakir’. (The Mahatma had himself spent the last decades of his life in a semi-naked khadi in seeking to identify with India’s poor masses.)

Gandhi dehumanised blacks, noting that ‘Kaffirs are as a rule uncivilised … They are troublesome, very dirty and live almost like animals’. Continuing this repeated ‘Kaffir-bashing’, Gandhi complained in 1895 that Indians being given a lower legal standing than whites would impact them ‘so much so that from their civilised habits, they would be degraded to the habits of the aboriginal Natives’.

Many of the Mahatma’s later apologists have sought to portray his racism as that of a young twenty-four-year-old-lawyer newly arrived in a country that he clearly did not yet understand. But as late as 1908, at the age of thirty-eight, Gandhi was still spewing racist venom, noting that ‘The British rulers take us to be so lowly and ignorant that they assume that, like the Kaffirs who can be pleased with toys and pins, we can also be fobbed off with trinkets’.

5. Apostle of Social Apartheid

Even before the National Party enshrined apartheid as state policy in 1948, the South African Gandhi was a staunch believer in social apartheid. He launched several campaigns that successfully established separate public facilities for Indians and blacks. In 1895, for example, Gandhi euphorically celebrated victory for having ensured separate entrances in the Durban post office for blacks and Indians, in addition to the white entrance. It was more the lumping of blacks and Indians together that outraged Gandhi, rather than the separation of whites from the darker races.

Gandhi further noted that ‘The Boer Government insulted the Indians by classing them with Kaffirs’. In 1904, while fretting about the ‘mixing of Kaffirs with the Indians’, he expressed outrage over ‘Why, of all places in Johannesburg, the Indian location should be chosen for dumping down all the kaffirs of the town …’ These words presaged the 1950 Group Areas Act by nearly five decades. In 1905, when a plague hit Durban, Gandhi noted that the disease would persist as long as Indians and blacks were ‘herded together indiscriminately at the hospital’. In 1909, the Mahatma was still seeking to ‘ensure that Indian prisoners are not lodged with Kaffirs’. In housing, hospitals, post offices, prisons, and toilets, Gandhi very much believed in the separation of Indians and blacks. In a precursor of apartheid’s 1950 Immorality Act, he further opposed Indians having relationships with black women, which he considered to be fraught with ‘grave danger’.

Gandhi thus sought political alliances with the imperial British rather than the oppressed black majority during his time in South Africa. In his voluminous writings about this time, the Mahatma mentions just three Africans, only one of whom—African National Congress leader John Dube—he had ever met. Gandhi certainly did not have black friends, let alone acquaintances, in two decades of living among a black majority. He regarded what he termed as culturally backward and intellectually inferior blacks, as irrelevant to the future of their own country.

6. Gandhi Falls in Ghana

As earlier noted, serious reassessment of Gandhi’s legacy achieved new momentum in academia with the publication of the book The South African Gandhi: Stretcher-Bearer of Empire by Ashwin Desai and Goolam Vahed in 2015. This re-examination spilled over spectacularly into the public sphere when staff and students successfully petitioned for the removal of Gandhi’s statue from the campus of the University of Ghana’s Legon campus in December 2018. The memorial had been erected six months earlier following a state visit by the Indian president, Pranab Mukherjee. Ghana’s foreign ministry and presidency had agreed to the erection of the statue before the university had been properly consulted. Though Legon’s senior management later approved the memorial, it was clear that there had not been wide consultation among the university’s students and academic and administrative staff. This was a top-down, state-led decision imposed—many felt—on the university community.

Shortly afterwards, academics and students at the university—backed by civil society activists—successfully raised a petition of over 2,200 signatures for the removal of the statue, arguing that Gandhi had been a racist, and that the presence of his statue on the campus was a particularly odious assault on the collective psyche of black people. Gandhi’s critics also argued that there was no memorial at the university to any African heroes, which they noted would have been more appropriate.

7. Concluding Reflections: Gandhi as Heir of Rhodes?

Gandhi’s life contained three great paradoxes: first, the prophet of non-discrimination expressed some of the most bigoted views against black Africans; second, the apostle of non-violence took up his stretcher to assist the British in waging imperial wars against oppressed Zulus; and third, the most renowned anti-imperial figure of the twentieth century collaborated with British imperialists to destroy the independence of black Africans.

Many of Gandhi’s apologists, such as the Indian writer and journalist Ramachandra Guha, have tried to excuse his prejudice by noting that he was a man of his epoch. Family members like granddaughter Ela Gandhi have argued that the Mahatma was being condemned based on ‘one or two statements’. Others have sought to portray his civic activism in South Africa as having paved the way for later black struggles. These patronising views, however, ignore two and a half centuries of black and brown resistance to British and Dutch colonisers in Africa and the east, long before Gandhi ever set foot in South Africa in 1893.

A statue commemorating Gandhi’s June 1893 expulsion from the first-class, whites-only compartment of a train—often identified as the catalysing moment in his struggles against colonialism—stands in Pietermaritzburg. Another stands in Gandhi Square, Johannesburg. Based on his utterances and actions, Gandhi was, however, clearly racist towards black people, and believed them to be inferior. After 1994, post-apartheid South Africa was on a quest to play out the myth of a ‘rainbow nation’ in the country’s great national dramaturgy of reconciliation. National heroes were needed across all races, and unity was stressed over division, even as deep wounds were papered over which did not fit the new official narrative of ‘no victors, no vanquished’. South Africa’s ‘Founding Father’, Nelson Mandela, rushed to embrace India’s own revered ‘Founding Father’ in noting: ‘He was both an Indian and a South African citizen … It was here that he taught that the destiny of the Indian Community was inseparable from that of the oppressed black majority’. Similarly, Mandela’s successor, Thabo Mbeki, opined that ‘Gandhi … spent many years in South Africa … during which he used his extraordinary energies to fight racism’.

But as extensively demonstrated above, during his years in South Africa, Gandhi fought a parochially Indian struggle which was completely separate from the struggles of the black majority. He pleaded with his British oppressors to accept Indian subjects as their equal, and uttered the most vile and vulgar racial insults against black people. He also supported social apartheid, failing to interact with the black leaders of the day, who were fighting for the most basic rights of the country’s majority.

There are parallels between Gandhi and the way that post-apartheid South Africa sought to rehabilitate the racist legacy of the imperialist Cecil Rhodes. Mandela himself unwisely linked his name forever to Rhodes in the ill-judged Mandela Rhodes Foundation in 2003, viewing this monstrous marriage as an act of reconciliation between the country’s black and white races. There were clear parallels between Rhodes and Gandhi: both were migrants who moved to South Africa in search of fame and fortune; both were British-trained lawyers and admirers of British institutions; both had laudatory hagiographies written about them before more balanced assessments emerged; and both have had their legacies re-examined, and their statues removed and/or defaced in Zimbabwe, Zambia, South Africa and Ghana.

Both Rhodes and Gandhi are often said to have been ‘men of their times’, and so not to be judged by the standards of our own age, yet there were surely many white and Indian individuals during the era—such as Olive Schreiner and Yusuf Dadoo—who supported the rights of the black majority and did not utter such vulgar racist slurs, practice social apartheid, or enable acts of dispossession of oppressed people.

It must be said, though, that Gandhi was also no Rhodes. After leaving South Africa in 1914, he lived another thirty-three years in India, where he fought an innovative, relentless and ultimately victorious battle against British imperialism. He also identified with and championed the rights of the poor masses of India. While neither Gandhi nor Rhodes can be exonerated by the fatuous argument that they were ‘men of their times’—we cannot apply different moral standards to the racism of both men without drifting into sophistry—what ultimately somewhat redeems Gandhi’s legacy is the fact that he was instrumental in destroying the edifice of British imperialism, resulting in the liberation of Asia and Africa. His satyagraha inspired African and American leaders like Nkrumah, Kaunda, Sadat and King, the last of whose struggle for Civil Rights ultimately made possible the presidency of the first African American, Barack Obama. As Gandhi’s biographer Judith M Brown put it, he ‘gave the world beyond India grand visions and hopes which have become a recurring inspiration to men and women of other times, other places and other cultures’. Gandhi ultimately ended up on the right side of history; Rhodes did not.

A statue of Gandhi was erected in London’s Parliament Square in March 2015, while others have been unveiled in the United States, Germany and elsewhere, but there is no question that his brand has been badly damaged by the revelations of his racism against black South Africans. The Indian government is still, nevertheless, traversing the world seeking to offer his statues to foreign countries. Cape Town was asked by New Delhi to unveil a life-size statue of Gandhi this year; a reported 60 per cent of Cape respondents did not want the project to proceed. In 2018, over 3,000 Malawian petitioners successfully opposed a statue of Gandhi being built in Blantyre. Gandhi’s statue in Johannesburg was defaced with white paint in April 2015 by protesters condemning his racism. A Gandhi statue in Davis, California, was also the site of protests in 2018.

Will the Gandhi statues in Pietermaritzburg and Johannesburg survive the harsh verdict of history? If both memorials are to remain intact, let them be augmented: a petition, please, for the South African government to erect a statue of John Dube in conversation with Gandhi in Pietermaritzburg, and another of Lilian Ngoyi—the ANC stalwart and key leader of the 1956 Women’s March on Pretoria—in dialogue with the Mahatma in the heart of Johannesburg.

- Professor Adekeye Adebajo is Director of the University of Johannesburg’s Institute for Pan-African Thought and Conversation, and the author of The Eagle and the Springbok: Essays on Nigeria and South Africa (2017).

There are a few critical points missing here.

1. Gandhi viewed white people as superior to indian people and not as equals..

2. The now racial slurs were not slurs at the time but normal words used to denote black people.

3. He also believed that white people were correct in colonising india whose people he saw as inferior despite the fact that the British were killing and stealing from the natives in india. This is very telling that he had been ingrained with very distorted beliefs.

His belief system stemmed not from a free society but from a colonial system where white people were on top and on the other side were those who didn’t look white, in SA it was the black people, in India it was the darker skinned indians. This was a belief system that virtually everyone in the colonial world was born with. People of colour were constantly trying to be as white as possible and to avoid being “othered” aka black because being white meant that you could have a better life and being black meant having a worse life. Noone (including white, indian, coloured and black) wanted to be labelled as “other” at the time and everyone did their absolute best to avoid it. This belief is still very ingrained in today’s society.

I, myself, lived during apartheid and that was a belief that MOST people had. Despite all this, he started to undo a large part of his mental conditioning at that time and evolved more so than the average person at that time.

What I do find odd however is the large number of people (from all races groups excluding black people) who claim to be surprised and appalled at Gandhi’s racism and then continue in their daily habit of excluding black people in social situations.

I am quite certain that a time will come (soon) when all groups will be interacting harmoniously.

I would like to get in touch directly with Prof Adekoye in regards to his publication regarding Ambassador Mahiga. Specifically the article was one of the best to be written on Mahiga, however we, those of us who worked closely with Mahigafor many years in his various capacities would wish to enrich the article further by providing more information to be published by Prof Adekoye.