Moshibudi Motimele reflects on the publication of Our Words, Our Worlds: Writing on Black South African Women Poets, 2000–2018, a new anthology edited by The JRB Patron Makhosazana Xaba.

Poetic intention expresses, reveals … [what] the people have not ceased to live in reality.

—Edouard Glissant, Caribbean DiscourseOne of the most powerful tools for refusing reductive visions is to recall the hidden lineages of Black women’s writing.

—Gabeba Baderoon, Our Words, Our WorldsIt is clear that very little research has targeted Black women writers as knowledge and content producers, through the medium of books, let alone poets.

—Makhosazana Xaba, Our Words, Our Worlds

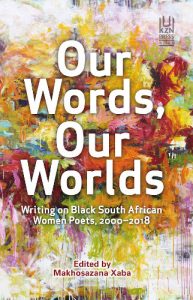

Our Words, Our Worlds

Makhosazana Xaba

UKZN Press, 2019

1. Decolonising the archive

That the modern colonial episteme is rooted in racist, sexist, ablest and heteronormative foundations is no longer a matter of contention. The question that haunts current activism around epistemic justice and decolonising universities in terms of curriculums and pedagogies, institutional cultures, hiring and promotion, assessment and student experiences is how best to confront this injustice, cognisant of the unlearning and relearning, breaking and recreating, burying and rebirthing that such a project requires. By harnessing the ‘invincible power’ possessed by Black South African women poets (Margaret Busby), OWOW—as the work under consideration here is known for short—emerges as an essential weapon in this fight.

Reading the work of radical Black women scholars such as Sylvia Wynter, Saidiya Hartman, Christina Sharpe and Hortense Spillers in her 2019 paper ‘Stolen Life’s Poetic Revolt’, Louiza Odysseos outlines three aspects of poetic revolt: i) critical fabulation, ii) world-making otherwise and iii) resignification. All three of these aspects are present in Makhosazana Xaba’s edited volume Our Words, Our Worlds: Writing on Black South African Women Poets, 2000–2018. It is an instrument of poetic revolt that simultaneously inscribes the work of Black women into epistemic archives from which they’ve been erased and creates the possibility for new threads of thought rooted in their experiences and narratives The book acknowledges the racist, male-dominated mainstream literary scene, while holding space for the ways in which Black women have disrupted its relevance by transcending their marginalisation through collective projects such as Feela Sistah!, Word N Sound and Jozi House of Poetry, and an insistence on their right to feel, speak, perform and be heard.

Following Hartman, ‘critical fabulation’ means the use of narrative to respond to archival omissions—and this is exactly what OWOW achieves. Throughout the book, different strategies are used to respond to silencing, erasure and marginalisation, as acts of revolt and resistance that respect even the agency involved in choosing not to say and address certain things. For example, in her essay ‘Black Women Poets and Their Books as Contributions to the Agenda of Feminism’, Xaba makes two powerful moves. The first is her insistence on reading Black women’s poetry collections as both ‘feminist acts’ and ‘literary events’. To Xaba, the texts read as collective works responding to and feeding from the culmination of universal feminist activism at a particular point in South Africa’s constitutional democracy. This insistence on the collectivity of the work and its feminist agenda directly confronts the trend of depoliticising and anti-intellectualising the work of Black women poets. Second, she is deliberate about the numerical representation of the material, offering it as ‘evidence’ and ‘raw data’, an act of restorative justice she proclaims, and I agree, as a tool of empowerment for young scholars such as me invested in shifting the epistemic terrain towards the visibility and veneration of the words and worlds made possible by Black women poets.

2. Homo narrans: The revolutionary subject of critical fabulation

In her essay ‘On Being a Closet Poet-Writer’, Sedica Davids shares the moment she realised ‘that to be seen, engaged and heard would not be my privilege’. The violence received by women in response to any type of non-conforming expression—be it hair, clothes, sexual behaviour or sexual orientation—was enough to discipline her and others to retreat or keep quiet about their lived experience. This is a context we know well: the policing of women, their thoughts, aesthetic, ethics and modes of expression remains a dominant characteristic of the society we live in. Against this backdrop, Tereska Muishond’s essay ‘Searching for Women Like Me’ describes her first encounter with Black women poets such as Napo Masheane and Ntsiki Mazwai, ‘vocal about a range of topics, including femininity, sexuality, politics and a variety of social themes’, which ‘galvanised my own spirit to speak my own truth and give voice to the myriad thoughts and feelings trapped inside me’. Hers is a common thread in the narratives presented in this text. The encounter with the rising voices of Black women poets post-1994 affirmed the alienation that the writers of OWOW experienced, not only vis-à-vis national culture but also in corporate spaces, institutions of learning, churches, schools and at home. Alienation was transformed into affirmation: their words made possible other ways of being Black women in the world—ways not solely defined by fear, anxiety, retreat and self-censure.

Part two of the book, entitled ‘Journeys’, comprises many personal narratives of prominent Black women poets, including Myesha Jenkins, Makgano Mamabolo, Lebo Mashile and Phillippa Yaa de Villiers. These narratives resist what Xaba calls ‘a society dominated by male poets, in which the ideology of sexism prevails’. They directly confront the erasure of Black women poets by taking up the mantle of Homo narrans—the one who tells stories—both to overcome the silence of the archives and to acknowledge the impossibility of their ever fully capturing their work. As Mashile writes, ‘It [poetry] gave many South Africans, especially women, the opportunity to participate in rewriting history, to belong, to contribute. For the first time the power seemed to be in our hands, and our voices, even outside of the political arena, worth listening to’. Thus OWOW reveals the unknown while simultaneously holding space for what cannot be known—for example, the dynamics at play in the moment of performance—capturing the essence of Hartman’s critical fabulation, what Xaba names as a stand ‘against marginalisation and erasure, speaking against epistemic violence’ and Busby summarises as ‘owning the issues, raising the questions and braving the voids’.

3. Cross-generational conversations, microworlds and Black polytemporality

Tavia Nyong’o’s book Afro-Fabulations adds to the growing work of Black scholars on the ways Black cultural life has never been totalised or precluded by ‘conditions of traumatic loss, social death, and archival erasure’. Black polytemporality succinctly exposes the complicity of static readings of time and temporality, periodisation and history in the reading of Black art and performance as out-of-time. In arguing that time is never ‘colourless’, Nyong’o emphasises that ‘Black art and culture take their own time’. VM Sisi Maqagi begins her essay ‘Leaping from Behind History’s Curtain’ with a declaration that Black women poets’ creativity ‘performs acts of deliberate insubordination as it situates itself in multiple temporalities, as it revels in breaking multiple imposed silences … declaring their discursive power and inscribing their presence, their existence’. OWOW is an encounter with this polytemporality, as the cross-generational narratives provided by these poets speak in complex and nuanced ways against the grain of simplified dichotomies such as old–young, past–present, radical–progressive, marginalised–free, us–them and colonialism/apartheid–democracy.

OWOW is intentional in offering a cross-generational conversation. Jenkins speaks with nuance of the dissonance between older struggle writers and their contemporaries in her essay ‘Feela Sistah! And the Power of Women’s Spoken Word’. Among the aspects that amplified this dissonance were the impact of hip-hop and the public nature of spoken word, which saw young ‘cats’ intentionally positioning themselves outside the literary mainstream. I think it’s important that Jenkins’s essay pays homage to collectives such as Timbila, Botsotso and WEAVE (Women’s Education and Artistic Voice Expression), which were significant in crafting a space for Black poets but might not be known by younger generations. The cross-essay conversations in OWOW are neither disjointed nor contradictory, even as they acknowledge the limitations and failures of different projects. Jenkins writes the history of how Feela Sistah! emerged, then eventually disbanded. Younger poets such as Muishond and Mashile discuss what this collective meant for their own journeys into poetry and subsequently performance and publishing. As Jenkins puts it, ‘we [Black women poets] stood together in a microworld of our own’. The intentionality behind the story of Feela Sistah! stands as a challenge to current organisational forms that also seek to create safe, non-judgemental spaces for women’s equality. Important lessons we can draw from their experiences are things such as the self-funding model and the ways they were intentional about ensuring they gave each other ‘equal speaking time to create equality’.

Jenkins reads the group as an incarnation of struggle poetry that was collective, inclusive and centred on women’s equality. Thus the group is not to be seen as a breakaway from earlier iterations of Black poetry but simply a new iteration folded into or out of an existing genealogy. With regards to the group’s break-up, Jenkins concludes, ‘At another level we had given birth to a child we didn’t know how to nurture and support.’ Can there be any clearer example of the authenticity and reflexivity with which Black women poets come in, through and out of space?

4. Poetry: A safe space for multiple consciousnesses and self-exploration

From observation, I have noted that an assumption we often make as young people in our demand for a world-otherwise is that we know who we are, where we come from and where we want to go. Our assimilation into white modes of being and rational thought have imposed ways of being that privilege certainty and deny or ignore the impact that the projects of colonialism and apartheid, and their afterlives, have left on our individual and collective being and consciousness. Often this leads to paralysis: we mute our insecurities, contradictions, trauma and pain in the hopes that radical posturing will achieve emancipatory ends.

However, the narratives of many poets in this instrument of poetic revolt, OWOW, open the door to another way, made possible by poetry. duduzile zamantungwa mabaso affirms in her essay ‘The Mother Tongue and the Poet’ that encountering poets Nomkhubulwane and Jessica Mbangeni introduced her to the power of vernacular poetry as a ‘vehicle of thought’ and demonstration of ‘the people’s self’, the space that makes self-determination attainable. Sedica Davids writes that she ‘had to find a way of being that was not reliant on physical space’—and that was poetry. Muishond describes her journey from thinking that poetry was an ‘undesirable luxury’ to the catharsis of her first poem, written in hospital while she was at depression’s brink. For Makgano Mamabolo poetry enabled not only the exploration of issues that were taboo for women but also a cross-generational conversation between her and her parents, as ‘it was through the poems that we shared that they understood me better, and I them’. The Black poets and poetry contained in OWOW empower a genre of human denied by the modern colonial episteme: that of the erotic, intellectual, labouring, sexing, writing, dreaming and creating Black woman. The same genre of human through which emancipatory futures and worlds will be birthed as she gifts us with words that forge critical socialities and rupture grammars of captivity.

It was Audre Lorde who affirmed that poetic revolt ‘is the skeleton architecture of our [Black women’s] lives … that remains when forms regarded as “real resistance” to dispossession and normalised disposability are thwarted’. Socially, politically and intellectually, narratives of the liberation movement and its nominal gains have indeed been thwarted in the current public sphere. In particular, the sustained violence and violation of Black women has been unveiled, brought forth from the interstices of secrecy and the private sphere. Wynter defines sociopoetics as ‘the generativity of social life under conditions of abjection and enslavement … the force of those who live outside of the epistemological constraints that define human life’. OWOW thus becomes the key text of South African sociopoetics in all the places where said texts have formerly not been kept.

Gabeba Baderoon reflects on reading the anthology of women’s writing Daughters of Africa in 1994 and feeling that it was an answer to a question that she had barely begun to ask. As I sit and think about OWOW, I can’t help but echo her sentiments. I know why the book is important as as a pedagogical device, as an archival submission and as an instrument of poetic revolt. But what is the question it answers? And what is the relationship between that question and our freedom? I am comfortable with not having answers to these questions. In a moment when the demand seems to be centred on rightness, righteousness, radicalness and ‘realistic solutions’, the seductive power of OWOW is that it affirms, in the words of Lebo Mashile, the world-altering nature of ‘falling in love with the uncertainty and not courting clarity straight away’.

- Moshibudi Motimele is an interdisciplinary PhD candidate at Wits University whose research and activism centre on questions of decolonising curricula and emancipating epistemologies. Follow her on Twitter.