In Beyond Babylon, by Igiaba Scego, migrants come to rebuild their lives in the midst of ruins, writes Francophone and Contributing Editor Efemia Chela.

Born in Rome in 1974 to parents from Somalia, Scego is an award-winning author in Italian, and her memoir La mia casa è dove sono (My home is where I am), published in 2010, won the prestigious Mondello Prize. Beyond Babylon was first published in Italian as Oltre Babilonia ten years ago. Aaron Robertson’s translation, published this year, is the second of Scego’s books to be translated into English. The first, of her most recent novel Adua, was translated by Jamie Richards and published by New Vessel Press in 2017, and is forthcoming from Jacaranda this month.

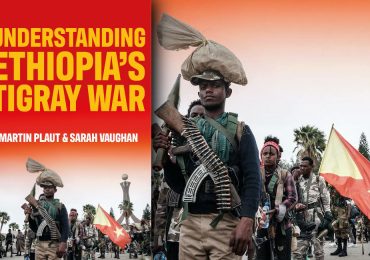

Beyond Babylon

Igiaba Scego (translated by Aaron Robertson)

Two Lines Press, 2019

I think of ghosts and haunting of just being alert. If you are really alert, then you see life that exists beyond the life that is on top. It’s not spooky, not necessarily. It might be. But it doesn’t have to be.—Toni Morrison

Igiaba Scego’s novel Beyond Babylon follows a cast of characters whose early lives are forged in the crucible of war, then spent in emotional and physical exile in Italy. This is not your traditional immigrant novel: Somali–Italian Scego creates something more shifting, more difficult to pin down. (Italy itself was not a typical colonial master, specialising in occupations rather than the indirect rule of the Belgians or more direct rule of Britain and France.) True, we find the regular anecdotes of the outsider in its pages—hair conformity troubles, menial jobs, passport worries, and so on. But Scego is more concerned with turning the telescope the other way, towards the swirling insides of quietly eccentric family members, generational debts accruing interest, and the sins of the mothers.

The narrative is shared by two sets of families, the Gonçalves and the Laamanes. When Miranda Ribero Martino takes over the storytelling, often in the form of a letter to her daughter Mar, she is identified as The Reaparecida—the one who has reappeared. She harkens back to her life in Argentina in the nineteen-seventies, before she achieved success as a poet, a dangerous time. In 1976, her brother Ernesto was abducted and tortured in a centre called Esma, like thousands of others at similar sites during the country’s gory Dirty War, which lasted until 1983. She is still haunted by him and her own survivor’s guilt. She speaks of the war, saying:

They kidnapped our neighbours and we covered our ears as forcefully as we could. The soldiers turned the radio volume up … An entire country was desaparecido [disappeared]. Everyone pretended like things were fine. You went grocery shopping, you planned parties, you watched the World Cup.

The intrigue intensifies when Miranda reveals her love affair with a notorious torturer, Carlos, in the depths of her misguided grief. It seems to be a warning to her daughter about the romantic inclinations she could inherit, albeit one that comes too late. When Mar, known as The Nus-Nus, Somali for ‘half and half’, enters the book, she’s at the end of a turbulent relationship with a woman called Patricia, who, in a melodramatic chain of events, has coerced Mar into sleeping with a man and subsequently carrying a child for the couple. A few months afterwards, in a fit of caprice, Patricia changes her mind and forces Mar to have an abortion, then commits suicide. Mar is distraught, and sees visions of her in several places.

Scego, like Toni Morrison, populates her fictional universe with crippled survivors and the ghosts that plague them. There are desaparecidos, dead lovers, and emotionally absent fathers and husbands. They exist in the minds of the women who survived them as traumatic shadows, warnings unheeded and—occasionally more positively—infinite possibilities for alternate histories and futures.

In a novel of such grand measure, the best moments in Beyond Babylon happen in its tiny corners, not on the main stage of ideas, where the action can be overblown. Mar and Miranda’s relationship, while perhaps not as fraught as in other writer family rivalries—like Kingsley and Martin Amis (father vs son), or AS Byatt and Margaret Drabble (sister vs sister)—holds lucid observations of what goes unsaid and unconsidered, when a family member devotes their life to, in this case, poetry:

Mar envied her mother’s readers, they understood her and she put in tremendous effort for them … They cried when the poet cried. They sighed when she sighed. Everyone was perfectly symbiotic. Only she, Mar, remained outside her mother’s chorus and heart.

Zuhra, who goes by the title The Negropolitan, is similarly estranged from her mother, Maryam Laamane, whose story is one of the richest in the book. It weaves in and out of all the others, giving us a layered look at the traditions of Somali society through this flawed woman, ‘overcome by the foul odour of exile’, who goes by the title The Pessoptimist. Just a year before Ernesto disappeared in Argentina, Maryam leaves Mogadishu and the violence of Siad Barre’s dictatorship to join her husband Elias in Italy. Once there Maryam retreats into gin and nostalgia for a simpler version of her past, while leaving Zuhra to raise herself in an Italian boarding school. Her chapters are confessional, spoken into a voice recorder she plans to give to her neglected daughter as an apology, but also as a record of the woman she used to be, and the woman she tried and failed to become.

The two families twist towards each other through Zuhra, who first meets Mar in Rome, where she has come on a personal quest. In a magical realist plotline that is never fully resolved, Zuhra is unable to see the colour red, owing to sexual abuse as a child. She hopes that in Rome she’ll finally encounter the mysterious colour that eludes her. She also decides to study classical Arabic as a way of reaching towards the African part of her identity, something both she and Mar struggle with, as mixed-race women. While spending time with Mar and Miranda on their travels, it turns out the group have more than just their yearning to learn Arabic in common, and all the family histories spun throughout the book begin to knit together.

Scego’s modern rendering of Rome in Beyond Babylon is neither a glamourised twentieth-century Cinecittà set nor the heart of an ancient empire. It is a gutsy city where migrants come to rebuild their lives in the midst of ruins.

A note on August, Women In Translation Month

Language is migrant. Words move from language to language, from culture to culture, from mouth to mouth.—Cecilia Vicuña

Beyond Babylon, written in Italian, and to a lesser extent Spanish, Somali and Arabic, was selected to be featured in The JRB to celebrate Women in Translation Month (#WITMonth), which is Christmas, Eid and Dezemba rolled into one for global literature fans.

Women in Translation Month occurs every August and highlights works by women writers that make their way into English translation, and thus discover a wider audience. It was the brainchild of Meytal Radzinski, an Israeli scientist, and has grown from strength to strength since it was founded in 2014. It is estimated that still only about three per cent of books in the UK and USA are works in translation, but initiatives like #WITMonth are opening the minds of editors, publishers and readers to the idea that works in translation are worth supporting and integral to bibliodiversity.

If you want to get started reading more women in translation, take a look at Meytal’s 2019 list of one hundred of the best, voted for by members of the public. She says:

The idea was to create a new canon of sorts. Every reader could send up to ten nominations of books written by women, trans, or nonbinary authors, originally written in any language other than English. Ultimately, almost eight hundred unique books were nominated. Most of the titles only ever had a single vote, but it speaks to the passion and love that readers have for women writers from around the world that we reached such a number.

- Efemia Chela is Contributing Editor. Follow her on Twitter.