The Troubled Times of Magrieta Prinsloo by Ingrid Winterbach offers us one of the most chilling and fearless portraits of this present moment of local and global crisis, writes Patrick Flanery.

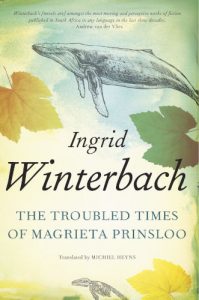

The Troubled Times of Magrieta Prinsloo

Ingrid Winterbach (translated by Michiel Heyns)

Human & Rousseau

1.

Stellenbosch. Late winter. (Or, perhaps already, early spring.)

This is the season when the sandstone mountains glow blue and grey at midday, when climate change brings weeks as scorching as an equatorial summer followed by cold fronts that arrive with howling winds, torrential rains, snow on the high peaks, and temperatures in the valleys that nonetheless stay comfortably far from freezing.

This is the season when undergraduates, returned to a city where everyone seems preternaturally fit, are always running, throwing themselves up the trails on Stellenboschberg, exercising furiously in the world-class university gymnasium, hiking in the Jonkershoek Nature Reserve, cycling off road and on. (The spirit is infectious. My husband and I join the gym and employ a personal trainer for the first time in our lives. Is it possible, I ask him, that all this physical activity is inflected by a feeling that one needs to be prepared—because this is a time when anything could happen?)

This is the season when the scent of dagga drifts through streets lined with multi-million-US-dollar mansions first thing on a Sunday morning.

This is the season when a man’s body is found on the edge of an informal settlement with legs missing and the authorities attribute his grisly death to a wild animal. Local community leaders suggest an animal would never take only the legs and leave the rest of the body. At dinner parties in the affluent suburbs, people speculate about whether it might have been the work of an elderly leopard too weak to go after buck but still hungry enough to try for a human gathering firewood. Still others hazard it might have been a serial killer. There is more than one body, isn’t there? Headlines suggest there is, and then don’t. What seems factual one moment feels, weeks later, like a trick of memory.

This is the season when, for weeks, I pass the corpse of a cat ignored by scavengers, its white body languishing in the grass outside the Jan Marais Nature Reserve, coat turning brown, skin drawing back so its teeth glint in the sun as its hindquarters become progressively less feline, more like joints of unidentifiable meat: mammalian, reptilian, even avian.

This is the season when wine farmers are reeling from the murder of one of their own by masked men, when people in the township of Kayamandi are protesting inadequate housing, and when one of their own, a community leader, is murdered in what the media describes as a ‘hit’. The press seems divided about whether this second killing is the result of factional infighting in the protest movement or might be related to the murder of the white farmer, whose death remains under investigation.

This is also the season when a friend suggests that instead of taking orders from India (i.e., the Guptas), the ANC is now taking orders from Stellenbosch, a charge echoed some weeks later by members of the EFF.

This is the troubled time through which we are living, and the troubled time of Ingrid Winterbach’s searing new novel, translated from the Afrikaans by Michiel Heyns. Which is not to suggest that Winterbach’s book is overtly preoccupied with crime, politics, or the environment, but all of these elements are inescapably present around the edges of the text as reminders of the social turbulence at play—and not only, of course, in South Africa.

2.

In the original Afrikaans, the title of Winterbach’s twelfth novel, Die troebel tyd, speaks of its temporality in the broadest sense. It is a book deeply invested in exploring the horrifying weirdness of this particularly troubled, turbid, murky time, and not only the more personally troubled times of the novel’s protagonist, zoologist Magrieta Prinsloo. (The English title of the translation suggests a certain cuteness at odds with what is arguably one of Winterbach’s most serious and accomplished works.) Its preoccupation with climate change, species loss, inequality, precarity, social unrest, neoliberalism, artificial intelligence, and the post-human makes it a book urgently of its time, one whose masterfully controlled illumination of how it feels to attempt to live an ethical or even ordinarily responsible life, to be attentive to all that is unsettling and unjust in the world around us, cannot be ignored.

Dr Prinsloo, a successful academic whose research on the prehistoric evolution of the earthworm has powered her rise to be ‘head of a laboratory with twelve people under her’, succumbs at the start of the novel to a crippling depression that causes her to torpedo her career, resign her position, and alienate her husband, Willem. When she eventually surfaces from this malaise, medicated and having regained her equilibrium after months of the depression that attacks her ‘furiously’, ‘[h]ectically’, even ‘virulently’, Magrieta goes to work for an organisation called the Bureau of Continuing Education, under the supervision of the Cape branch’s director, the enigmatic Markus Potsdam. The new job requires travel throughout the Western and Eastern Cape provinces to meet with a series of ‘Agents’, who are frequently as mysterious or as menacing as their title suggests. It is this travel, in the company of Magrieta’s young assistant, Isabel Durandt (a recently minted and amusingly foul-mouthed computer scientist specialising in neural networks), and their joint negotiation of an enervating working relationship with Potsdam—himself violently depressed—that fuels the novel’s unflinching surveying of the state of humanity now.

I say ‘surveying’ because this is a book less concerned with diagnosing what is broken in the world than in describing a landscape of places and events that bewilder and unsettle. On her first business trip in her new position, Magrieta travels to the Eastern Cape, to a thinly veiled Makhanda/Grahamstown, appearing here as ‘Albany West’, where she meets one of the Bureau’s potential new Agents, the Heidegger-reading palaeoclimatologist Jerry Oliver. Oliver, who uses a wheelchair, is the first in a series of characters that afford the novel a sustained engagement with David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest and its cohort of wheelchair-equipped Québécois separatists, Les Assassins des Fauteuils Rollents [sic].

Dogged by a ‘seeping greyness’, Magrieta registers ‘something violent brewing in the atmosphere’, ‘the sky … a treacherous greyish-pink, with sulphurous yellow undertones’, as she makes her way through the town’s crumbling, potholed streets, encountering one wheelchair user after another (Albany West, it turns out, is hosting a convention of wheelchair users; later, Magrieta will meet a group of wheelchair-equipped environmental activists). While Foster Wallace deploys his wheelchair assassins mostly for comic effect, Winterbach allows encounters with disability to illuminate how physical difference can be experienced irrationally, by someone like Magrieta, as a potential threat.

There is nothing glib about this. Rather, Winterbach manages with exceptional stylistic and narrative poise to present the theme in such a way that what first appears absurd becomes, through slow revelation, a series of encounters that are deeply affecting. As the movement of New Sincerity—of which Foster Wallace was guru and chief exponent—ostensibly eschewed the ironic without sacrificing the weird, the absurd, the surreal, or the comic, so Winterbach manages to martial such modes without relinquishing moral seriousness. And yet, at the same time, she seems to want to insist on the possibility of retaining such metafictional possibilities as New Sincerity so often refused. There are moments in The Troubled Times that speak directly to its own literary form, to the range of possibilities available to the author, including a short and arresting chapter that catalogues varieties of character trajectories and types, suggesting what Magrieta might be or do, and how we, her readers, might choose to understand her:

Characters who get into cars and drive to places where things happen to them—pleasant as well as unpleasant things. Like being shadowed by a stalker, or attacked and robbed in the street, or falling and being injured … [A] character can decide that the only way of gaining control over her life would be to go and stay for a while in isolation in a friend’s beach cottage.

The oscillation between options that seem banal and those that are cataclysmic suggest how Winterbach is constantly engaged in mining the narrative possibilities of the everyday and finding within them the kind of horror that has become so normalised as to seem banal to those who live with its daily threat.

As well as the intertextual references to Foster Wallace, there are other moments in The Troubled Times that suggest frames through which we might read Magrieta’s story, which is—it is worth repeating—less a tale of her specific time than a narrative of these times as they unravel violently around us. This is a book that engages with the everyday weirdness of contemporary life, one in which WhatsApp messages from strangers fly into Magrieta’s phone recounting events and individuals about whom she knows nothing. Winterbach mobilises Magrieta’s encounters with the sublime to animate how, in the midst of environmental crisis, experiences of wonder at the scale and beauty of the natural world have the capacity to re-sensitise us to all that we risk losing through our own greed and carelessness. This even as we rush headlong to replace nature with technological simulacra—as does the novel’s Deneys Swiegers, an academic engineer developing a ‘soft’ robotic duck.

Such elements might suggest the operation of a surreal impulse, but as with the allusion to Foster Wallace, Winterbach gives us subtle clues about how to understand what she is doing; while operating entirely on its own terms, the book nonetheless teaches us how to read it. When Magrieta meets with ‘Agent’ Nonki Jansen van Rensburg, an idealistic young English literature academic who runs a drama outreach project in the township bordering Albany West, Nonki invites Magrieta to a lecture on ‘bizarro fiction’ given by an academic, writer and musician who might or might not be the Icelandic pop star Björk. Plus ça change, plus c’est bizarre. Although Winterbach’s novel does not obviously fit within the confines of the ‘bizarro’ genre, she certainly seems attentive to that genre’s interest in the absurd, the more generally weird, the satirical (although hers is not a work of satire), and in speculative fiction (although there is nothing speculative about soft robotics, or, indeed, robotic ducks; they exist already in the world).

Alongside New Sincerity and that which might be judged bizarre or bizarro is, I think, a third key to understanding the novel in the shape of a submerged reference to Argentinian novelist César Aira’s An Episode in the Life of a Landscape Painter. Magrieta’s novelist friend Jakob (who also bears a passing resemblance to Foster Wallace) has recently read Aira’s magisterial short novel about nineteenth-century German painter Johann Moritz Rugendas. He recommends it to Magrieta, describing the way ‘a brief and dramatic incident in the Argentinian pampas … interrupts [Rugendas’] travels and brands him for the rest of his life.’ This is an understatement: in Aira’s novel, Rugendas is struck by lightning, nearly killed, and never sees the world the same way again.

Moments of comparably transformative force occur when Magrieta has two encounters with whales: one dead, one living. The first encounter begins to alter her thinking through recognition of the creature’s enormity and the tragedy of its loss (which is curiously intertwined with the discovery nearby of the body of a man who has been stabbed to death on the beach):

A dead silence descends. A silence as if under a bell jar. Magrieta gazes with awe and wonderment at the dead creature. … She looks into the milky, unseeing eye. … She lays her hand carefully on the gigantic flank. … Magrieta is overwhelmed. She is deeply moved by the presence of the gigantic apparition from the depths. The leviathan. … In her head she feels a small shift, like two tectonic plates sliding over each other.

If her confrontation with the dead colossus lays the groundwork for a radical shift in perception, the second encounter is nothing less than a direct experience of the sublime. On a beach, wheelchair-powered environmental activists present at a distance, Magrieta finds herself sole witness to a baleen whale flying from the water:

[W]hen she opens her eyes, by God, high up in the air, high, far away, some distance deeper into the sea, but clearly visible, right in front of her unbelieving eyes, a gigantic whale leaps out of the water, graceful and ecstatic, and lands back in the water with an immense splash. And not just once, but again, a second time! The long fluke clearly visible, the hide shimmering in the tremendous rain of spray, the vertical belly grooves unmistakable. … Magrieta lurches forward onto her knees on the sand, scrambles up, her mouth opens, and strange sound emanates from her throat. She has to laugh. She has to laugh in disbelief. … For her eyes only that animal leapt from the water, let himself be seen. … She has to think of Jonah. She has to think of Moses and the burning bramble bush. And thrown into the mix other miracles and revelations and annunciations—also the whore who arises from the seas in Revelations.

After this, Magrieta’s own vision of the world, like Aira’s fictionalisation of Rugendas’s, seems irreversibly altered; she is preoccupied, too, by William Blake’s The Sick Rose, with its ‘invisible worm / That flies in the night / In the howling storm’. The worm, here, for Magrieta, might be the sense of menace that haunts her world, erupting into visibility in moments that register the violence of our times, and threatening to destroy all that it meets.

Sublime, weird, sincere. Each frame for reading works on its own terms, but viewed together they allow us to see the space-time of the novel and its aims in the round. This is a work of literary cubism, requiring that we remain attentive to the way the shifting (and recombining) of its stylistic and critical frames means characters and the events they experience are legible as informed by multiple literary traditions and movements, creating a narrative location and temporality that feels utterly of its moment.

3.

In Winterbach’s rendering of the world, time is constantly, rapidly passing. Sixteen weeks fly by in a sentence, another few in a phrase, two in an instant. Suddenly it is June, August, September, then a year has passed and it’s August again. Time is passing so quickly, the book seems to be saying, that we can’t possibly get a handle on what is actually happening. The scale and pace are simply too great. But make no mistake, something is definitely happening. In an extraordinary chapter in which Magrieta has a series of encounters with a woman exhausted by Afrikaner culture who checks out of her privileged life to take up residence in a tent pitched in a Stellenbosch vineyard, the novel reminds us of the chaos in the background:

It’s an exceptionally unstable time. In spite of the rain the drought has still not broken. Never before have there been so many mountain fires. (Often the work of delinquents and arsonists.) In some towns there is no water. There are riots and demonstrations about service delivery everywhere—burning tyres in the streets, stones thrown at motorists. Schools and factories are burnt down, buses are torched. There are taxi wars and gang violence. Students demonstrate about tuition fees. Statues are vandalised. The continuing drought, the weak economy, the dissatisfaction with local municipalities and corrupt government functionaries all contribute to the tide of unrest and uprising washing over the country.

In the maelstrom of a world that seems to be rapidly coming apart and hurtling towards its own demise, one can be forgiven for searching (however vainly) for an explanation of how we have arrived in this situation, how we have allowed humanity to be hijacked by its own social formations, by our technology, and our species’ insatiable craving for progress. It is no accident that Winterbach’s novel features characters who are experts in sciences devoted to the pre-human period, people who might tell us something about how the Earth was before the Anthropocene, and what this portends. Jerry Oliver, Magrieta thinks, might offer her an explanation for ‘how an inquiry into the climate of the Cambrian explosion could shed light on future climatological developments on earth’. Such interest is an ongoing theme in Winterbach’s work. In The Book of Happenstance (2008; originally published as Die boek van toeval en toeverlaat, 2006), protagonist Helena Verbloem is preoccupied with evolution and species loss; she befriends a palaeontologist, investigates the earth’s geological periods, and thinks about astrophysics. The supposed certainty of these scientific fields, however, provides no genuine consolation, even as they stand in contrast to the ways that crimes (the theft of a collection of shells, the murder of a man) remain unsolved and seemingly unresolvable.

Perhaps in this case, the answer—the why behind the horrifyingly weird—lies in the shadowy donors Magrieta must court, men who are ‘brusque, patriarchal, moustached, with a belly, a suntanned neck, thick, hairy fingers’, men who have made their fortunes exploiting the African continent and seem touched by the spirit of a shadowy military-industrial complex. Or perhaps the answers are encrypted in the graffiti messages that seem to pursue Magrieta, koki-penned missives exhorting her to ‘BE MINDFUL OF THE LEVIATHAN’ or, more plaintively, to ‘CONSIDER THE LEVIATHAN’, always illustrated with pictograms of amoebic-looking whales. The desire for explanation and the kind of master narratives that once provided easy consolation remains acute, even as the satisfaction of explanation and resolution is endlessly and realistically deferred.

On the far right, what feels broken today is often explained by resort to conspiracy theories infected with racism, anti-Semitism, homophobia, and other reactionary biases. On the far left, our present crisis is often explained by resort to conspiracy theories marked less by bias (although anti-Semitism is certainly present in some quarters of the left) than by a diffuse hangover of nineteen-sixties paranoia. This paranoia invests national intelligence, the military, and corporations with unbridled power to pull the strings of individuals and nations in a way that makes us all twitch to a plot that remains obscure, but which, we are certain, explains the social torsions that produce inequality, injustice, precarity and environmental crisis. If only, some of us might wish, we could draw back the curtain to see the men furiously pushing and pulling the levers that control the spectacle of power that, in turn, seeks to control every decision we make.

This is, in part, what Magrieta seems also to wish for: a drawing back of the curtain to reveal the source of what is going wrong around her. But the suspicion that there is a hidden explanation for the chaos marking our time can also threaten to obscure the actual causes of events that strike characters as mysterious or inexplicable. Sometimes the answer is simple: politicians are corrupt, people steal and kill, inequality erodes the social fabric, and capitalism is destroying the planet.

4.

Winterbach has an uncanny talent for engaging with the specificity of the places she writes about (here chiefly Stellenbosch and the fictionalised Grahamstown) in a way that requires no special knowledge of the reader unfamiliar with them, while still offering those of us who have spent extended periods in either place a frisson of recognition by turns painful (Grahamstown suffers most in this regard) and hilarious.

South African fiction has often struggled to negotiate this difficult dynamic, either to do justice to the particularity of place and represent complexity with accuracy, or to write more allegorical fictions that, in aspiring to the kind of universality that might allow a novel to travel to readers in other nations and languages, flattens out details—vocabularies and everyday cultural references unique to the country. Those books that occupy the former category, great as they often are, rarely gain traction abroad, while those that do manage to travel are often criticised (usually locally) for selling out to a notional northern market.

Winterbach’s fictions seem to me neither to sacrifice the richness and particularity of their South African settings nor to be so specific that they require special knowledge. Context is always sufficient explanation for local detail. That Winterbach has not had the success abroad she undoubtedly deserves says more about literary markets and northern publishers’ (and some readers’) resistance to (only ostensibly) South African stories than it does about the work itself. Winterbach’s fiction is of equal power and sophistication to that of JM Coetzee and Nadine Gordimer, while remaining entirely its own original project, as different and accomplished as work by other writers (Zoë Wicomb and Marlene van Niekerk, for instance) who, while enjoying a measure of international recognition, have not yet won the readerships their own work also unquestionably merits. (That we do not yet have all of Winterbach’s earlier books available in English is inexcusable.) Offering us one of the most chilling and fearless portraits of this present moment of local and global crisis, The Troubled Times of Magrieta Prinsloo provides confirmation, if we needed it, that Winterbach is among the most gifted writers currently at work. She has managed to distil in the most assured and controlled style all that is dementing and bizarre (if not bizarro) about our terrible times.

The author wishes to thank the Stellenbosch Institute for Advanced Study for an Artist-in-Residence Fellowship during which this piece was written.

- Editorial Advisory Panel member Patrick Flanery is the author of four novels, most recently Night for Day (2019), as well as a hybrid creative-critical memoir, The Ginger Child: On Family Loss and Adoption (2019). He is Professor of Creative Writing in the School of English and Drama at Queen Mary University of London and Professor Extraordinary in the Department of English at Stellenbosch University.

A superb, inspired and inspiring review of this compelling novel by a writer who should be on reading lists across the world. I could not think of a better review of a writer who stands amongst the best in the world.