Eben Venter presented the world debut of his first visual exhibition, ‘Translate Yourself’, at the February Lectures conference at the North-West University’s Potchefstroom campus at the end of February.

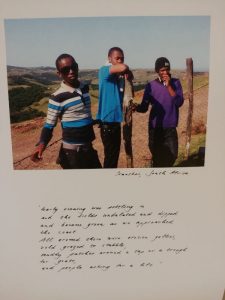

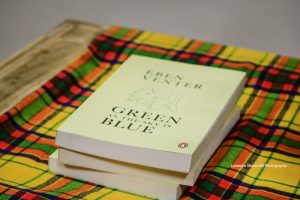

The exhibition consists of forty-nine photographs, each with corresponding text from Venter’s latest work, Green as the Sky is Blue (Penguin Random House)—the first of Venter’s novels composed in English, and thereafter self-translated into Afrikaans. Various locations and settings from the novel are recognisable in the visuals—Bali, Istanbul, Tokyo, the Netherlands, and South Africa’s Wild Coast—in unambiguous contrast to the distinctly stark architecture of the exhibition venue, the Heimatsaal (once a male hostel, and now one of the oldest and most iconic buildings on campus).

It was a homecoming (of sorts) for Venter: during the nineteen-seventies he attended NWU (then still called the Potchefstroomse Universiteit vir Christelike Hoër Onderwys). As we walk around campus—a campus which today feels joyously different from when I completed my undergraduate work at NWU ten years ago—he remembers the ultra-repressive environment: ‘Even jeans were banned’, he remarks, chuckling. The remark seems offhand, but it activates something; there is a quiver in his voice, a furtive look that betrays a very clear affective memory from the past. The nineteen-seventies saw the height of white insecurity and disinformation, and it couldn’t have been easy for more liberal-minded students, such as Venter, to navigate the masculinist constraints and Afrikaner-nationalist expectations of the campus. In a sense, it is exactly this aspect of his oeuvre that resonates most with me: the intense thematic consideration of how men navigate national frameworks of belonging.

In a similar way, the ‘Translate Yourself’ artist statement describes Venter’s process as concerning itself intimately with navigating various ways and modes of translation (between English and Afrikaans; between language and visuality) as well as with a recognition of the impact of recursive movements to-and-fro between sexuality and the linguistic; a meditation on the potentiality of movements between body, word and image.

One aspect that stands out is how much of the ‘meaning’—or even the enjoyment—a viewer constructs out of ‘Translate Yourself’ is not necessarily only in the way Green as the Sky is Blue is referenced, but in the myriad call-backs to the larger Venter literary oeuvre. I am intrigued by the potential of reading Venter’s visual work superimposed onto his books, mapping it onto my affective—and, admittedly, highly subjective—orientation toward his body of literary work. (The phrase ‘translate yourself’ being read not only as imperative statement, but also as DIY instruction.)

Over and above aesthetic considerations, then, lies a baser question on how we would construct meaning from such a very self-referential reading of the visual work, a reading so intricately constructed around the ways it refers back to the thematics, characters, and affective texture of the totality of Venter’s oeuvre. And, as the oeuvre is not explicitly referenced (barring Green as the Sky is Blue), the references we bring to the reading/viewing constitute lapses, referential spectres that work against traditional notions of word-visual translation fidelity (a fidelity that seeks to find, assign, correlate and master meaning).

Over and above aesthetic considerations, then, lies a baser question on how we would construct meaning from such a very self-referential reading of the visual work, a reading so intricately constructed around the ways it refers back to the thematics, characters, and affective texture of the totality of Venter’s oeuvre. And, as the oeuvre is not explicitly referenced (barring Green as the Sky is Blue), the references we bring to the reading/viewing constitute lapses, referential spectres that work against traditional notions of word-visual translation fidelity (a fidelity that seeks to find, assign, correlate and master meaning).

Instead, in the proud tradition of queer theory’s prodding of set identitarian assumptions (and, in keeping with the February Lectures focus on queer theory), the viewer plays with notions of fidelity, episodic moments, intimate confluence between visual and text. What do the gaps, the holes, the opacities between mediums signify? And what do they signify in terms of larger frameworks of belonging, in terms of national belonging, in terms of citizenship?

In this way, we get to read Venter’s visual work not primarily with the aim of setting up a relation of correlative fidelity between the photographs and the ‘corresponding’ passage from his narrative work. The gaps in reference echo the specific geocultural location of the Heimatsaal (the word ‘heimat’ resounding inward towards—and against—notions of homecoming and belonging) as exhibition venue. Other contrasts stand out: on a table, adorned with a bunch of bright yellow sunflowers (a shock of colour against the drab grey and browns of the building’s bureaucratic interior), lie four copies of Venter’s latest novel; the pale yellow of the covers—a paleness that emphasises that line drawing by Jean Cocteau—echoed in photographs a few metres away. It’s a spatial echo, and emblematic of how close the novel and visual works’s thematic concerns lie, especially in themes such as the forms of desire, notion of home(s), spatial belonging, and abject desire.

But for me it’s mostly male desire, in variegate forms, that runs through a large number of the forty-nine pieces, and that connects the parts of the whole. Themes of ferality and of fractured masculinities refract back; themes I read into and onto the series of photographs because that is how I’ve been reading Venter’s body of literary work. The novels, physically absent here, impact my reading of the photographic work; the assemblage-of-forty-nine becoming more than just the sum of its parts, but simultaneously incomplete without considering the oeuvre.

There’s a good dose of theory, too, to be found in the passages quoted below each photograph. A lot of Michel Foucault. In the artist statement, Venter echoes Foucault when he describes how the protagonist of his novel ‘creates a new way of being where he can invent and multiply and modulate himself, in order to translate his sexual experiences—and, most importantly, self-translate himself’. A number of the photographs echo this aim towards self-renewal, self-regeneration.

Still, I struggle to immerse myself fully in the visual work—to make sense of them affectively—without thinking of the novels. It’s a queer relationship, this, between the quoted passages and the visual elements, between present visuals and absent oeuvre. Perhaps it’s productive to read the exhibition as a series of visualisations, or translations into the visual: of the diasporic relationship to Afrikaans; of the visualisation of an autobiography; as a way of bringing into the visual a relation to the larger oeuvre. Whichever way we cut it, the approach itself is a queer move on the part of Venter, a visualised attempt to step out(side) of the recurrence of novel, novel, novel.

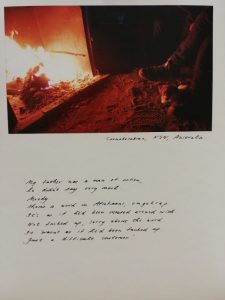

But it is also a move that breaks with the centrality of Afrikaans in the imagination of the Afrikaner diaspora. This occurs in both Green as the Sky is Blue and in ‘Translate Yourself’: instead of calling the Afrikaans version of the novel a ‘translation’, Venter sees it as a ‘second original’, while the artist statement acknowledges the ‘lilting ghost of Afrikaans’ in the quoted passages below each photograph. Some Afrikaans words stay untranslated in these passages—as when the text reads: ‘My father was a man of action, he didn’t say very much. Moody. There’s a word in Afrikaans, omgekrap.’ The use of Afrikaans and Afrikaans-isms is seen both as enabling and delimiting meaning, with the gaps between Afrikaans and English invested with meaning.

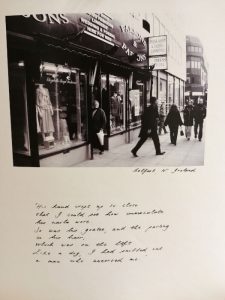

There’s also the sense that we can read the exhibition as a visualisation of an (auto)biography, a travel-writing-esque life story that seems to riff on the travels of the protagonist of Green as the Sky is Blue. But there are more gaps and lapses here: the photographs aren’t clustered neatly into corresponding spaces and, while the aforementioned cityscapes are recognisable, reference to the novel’s narrative devices that link the cities—and the corresponding making-into-a-sexual-self the protagonist undergoes in each cityscape—is lost. There are also ‘scenes’ depicted that don’t immediately correlate with events in the novel. Venter as persona is inserted too, in ways that the real Venter has always shied away from. (An implied refrain in interviews with Venter is that the novels shouldn’t necessarily be read as autobiographical.)

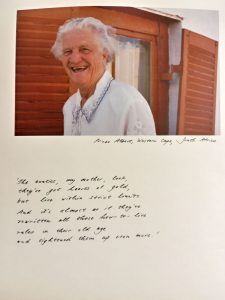

This insertion is another productive presence-as-gap: the author as persona identified by others close to him, in glimpses, for example of Venter’s mother, or of Venter’s partner Gerard Dunlop picking up a suit in Belfast. Also, some photographs are included that are simply too close to previous novels, thus disrupting clear-cut structural fidelity to Green as the Sky is Blue: the nude showering young man, for example, who could be Santa Gamka’s Lucky Marais—or not—activates in turn memories of the same novel’s Eddy and Eamonn, who might be Eben and Gerard—or might not be. With each photo, the references to the oeuvre (that I, admittedly, read into the visual work) become progressively more pronounced, and at the same time more opaque.

The meaningful gaps and productive lapses between specific visuals paired with specific chosen passages thus speak to the continuation of a decades-long creation of the authorial persona; a visualisation of a relation to the larger oeuvre intersecting with elements of a curated (auto)biography.

Numerous themes and places resonate around this intersection, but especially those associated with male fragility and feral masculinity. I’ve often found myself reading a specifically resilient fragility onto the men in Venter’s oeuvre. Oftentimes, his novels chart the particularly material how-to of male belonging, considered in all its earthy, musky molecularity, without shying away from incorporating the abject. I think immediately of the pronounced olfactory intimacy of Wolf, Wolf, or the sweaty clay-and-dirt-on-the-skin of Lucky Marais, stuck in a potter’s kiln.

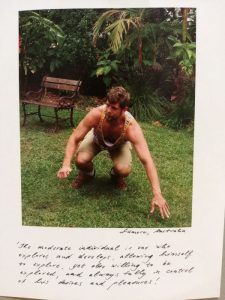

One photo stands out for its contained masculine ferality, the way it revels in the eager beauty of the male form: James Kilohertz, photographed in Venter’s back yard in Lismore, bends down on the grass to do a handstand, his vastus medialis taut and expression promising, eyes shyly upward and looking out toward the beyond of the frame, his pose and kinetic demeanour eager to please, eager to show off.

For me, perhaps inexplicably, there’s a bit of Santa Gamka’s Rooibaard in this photograph. And a bit of Wolf, Wolf’s Jack, with his dewy, mossy armpits. The garden setting brings to mind (the not yet translated) My Simpatie, Cerise. There’s even, perhaps, a bit of My Beautiful Death’s Konstant Wasserman (an affective echo—not a logical connection or direct correlate—which I haven’t yet properly processed myself). There’s definitely more than a bit of the connective ferality of Jack and Matt on Rondebosch Common. I know the Wollondilly of My Beautiful Death and the Rondebosch Common of Wolf, Wolf are completely different spaces, but in this one photograph they are both activated, resonating together with equal affective urgency.

So there’s productive meaning in the relation with the oeuvre, with affective meanings arising in the gaps, in the lilting ghosts, between the visual work on display here and the viewer’s memory of the novels.

Seeing the potentiality in the relation between photograph and quoted passage opens up to the beyond of the text, allowing us queer effractions (to use John Champagne’s term) into larger frameworks of belonging. To return to Venter’s artist statement, this work seeks to visualise ways with which to ‘invent and multiply and modulate himself, in order to translate his sexual experiences—and, most importantly, self-translate himself’. The forty-nine-and-one texts (the visuals and the literary oeuvre) here come to resemble a set of potential points of translatable reference, ways of plugging into the oeuvre. What else is an oeuvre if not a porous and malleable sequence of affective potentiality; a series of moments of potentiality?

- Wemar Strydom lectures in Afrikaans literature at NWU and is co-convenor of the February Lectures initiative.

Thought provoking article.