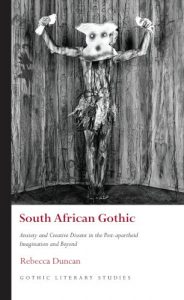

The JRB presents an excerpt from South African Gothic: Anxiety and Creative Dissent in the Post-apartheid Imagination and Beyond by Rebecca Duncan, part of the the University of Wales Press’s Gothic Literary Studies series.

From the blurb: ‘As the first sustained exploration of Gothic impulses in South African literature, this book accounts for the Gothic currents that run through South African imaginaries from the late-nineteenth century onwards’. For more on the book, scroll to the end.

In the following excerpt, Duncan uses SL Grey’s Downside trilogy as a lens to focus on the ‘mineral necropolis’ that is gothic Johannesburg.

~~~

South African Gothic: Anxiety and Creative Dissent in the Post-apartheid Imagination and Beyond

South African Gothic: Anxiety and Creative Dissent in the Post-apartheid Imagination and Beyond

Rebecca Duncan

University of Wales Press, 2018

Johannesburg

SL Grey’s Downside trilogy, marketed as the inaugural South African excursion into the field of horror, is an extended critical parody of neoliberal forces in an uneven post-apartheid South Africa that mobilises a lurid bodily aesthetic along with a ‘subterranean Gothic’ topography to skewer the ramifications of the neoliberal turn. The series sets up a dualism between the recognisable world of contemporary Johannesburg, and another society which exists ‘Downside’, below its surface. This universe acts as a grim distortion mirror for what is above, reflecting the unequal demographics, eroded state institutions and privatising impulses of post-apartheid South Africa in the language of exaggerated violence, nodding frequently, as it does so, to material continuities between past and present. Indeed, in the context of Johannesburg, the subterranean locus itself signals a particular relationship to the past: the city of Johannesburg is subtended by the craterous colonial and apartheid legacy of the goldmine. As Grey’s narratives chart the violences of the neoliberal agenda in post-apartheid South Africa in these bowels of the city, they thus suggest a linkage between the millennial moment and colonial capitalist endeavours in the age of mineral revolution. The mine—its coercions, exploitations and frequently fatal working conditions—is invoked in the Downside narratives as the heritage of contemporary economic protocols, participating in the constitution of a post-transitional gothic vocabulary that is local to Johannesburg.

Johannesburg is the largest city in South Africa, founded on the extraction of gold, and today—home to the Johannesburg Stock Exchange—the seat of financial power in the country. Under apartheid, like all South African settlements, it was rigorously segregated, organised by laws ‘aimed at driving noncitizens (i.e., blacks) out of sight, relegating them to the forgotten subterrains of the outer city’. Post-apartheid Johannesburg, in part as a result of its status as the local foothold of multinational enterprise, is a geography in motion. The city is ‘undergoing massive spatial re-structuring’, which, on the one hand—and to the extent that it entails the building of extravagant shopping complexes or luxury gated communities—participates in ‘setting up new boundaries and distances increasingly based on class’. On the other, as Mbembe points out, the reconfiguration of Johannesburg’s geography is also occurring visibly in more rhizomatic and unpredictable terms:

It is possible to observe such development in present-day central Johannesburg or in Hillbrow. For the most part the white population has abandoned these areas, leaving behind an infrastructure now occupied, inhabited or used by blacks in ways sometimes radically different to its original purpose … In the process Johannesburg loses its original contours.

What emerges from these diverse, uneven modes of restructuring is what Mbembe with Sarah Nuttall calls Johannesburg’s ‘Afropolis’: ‘an entanglement of the modern and the African … a city that has developed an aura of its own, a uniqueness’, and in which ‘the formal and the informal, official and unofficial, cohabit and at timesbecome entangled so that the city resembles now Los Angeles, now Kinshasa or Cairo, now all three at the same time’.

The dynamism of all of this notwithstanding, Johannesburg remains witness to the economic inheritance of apartheid: the disproportionate and racialised distribution of privilege and precariousness continues to structure the lives of its populations—those driven to the informal reclamation of inner-city infrastructure represent one example—and it is to this that Grey alerts us in narratives that play out in Johannesburg’s ‘underneath’, where there ‘lies a system that was based on a rigidly hierarchical division of labor, an original violence’. In Grey’s novels there is what Mbembe and Nuttall term ‘a subliminal memory of life below the surface, of suffering, alienation … the powerful forces contained in the depths of the city’; but there is also an insistence that such suffering is not only a memory, that it exists, resurgent, in mutated form. The space of the mine below the city is, in these narratives, the site of accumulated histories of ruination; it is a zone in which the injurious effects of layered pasts and presents are laid bare in gothic terms.

The vision of Johannesburg’s ‘necropolis’ is a signature topos in post-transitional gothic imaginings of the city, but it is one that recurs, too, across earlier South African writing in terms that prefigure its millennial reactivation as a locus of horror. In his 1946 Mine Boy, Peter Abrahams had already set out, in frequently visceral terms, the fatal ramifications of mine work on the bodies and minds of black miners: he presents, indelibly, the scene of ‘the man who spat blood’, dying of silicosis from the inhalation of dust, but working nonetheless so that his family will not be left destitute. In Maishe Maponya’s ‘The Hungry Earth’ (1978), the apartheid-era mine is figured as a cavern that ‘had opened to swallow the black man’. ‘I looked back into the tunnel where my brothers were being eaten by this hungry earth’, Matloko, the central voice in the play, tells: ‘I cursed the white man … for it was my sweat and bones and blood that made Egoli what it is today’ (p. 21). The cavities forged by such bones and blood are conjured in properly gothic terms in Marlene van Niekerk’s post-apartheid Triomf, where Treppie tells his family that the city is ‘hollow on the inside. Not just one big hollow like a shell, but lots of dead mines with empty passageways and old tunnels … that’s why it’s become so expensive to get buried in Jo’burg. There just isn’t enough solid ground left for graves.’ Johannesburg is also gothically hollowed out in Lauren Beukes’s Zoo City (2010), to which I will return in greater detail later in this chapter: the novel reiterates something of Treppie’s connection between the mine and a past that cannot properly be laid to rest, but explores this relation in terms of the active debris of apartheid in the present. Beukes’s mine is the vast, abyssal receptacle for the detritus of the city, which includes a gang of dangerously desperate and homeless teenagers, intent on harvesting the protagonist for her saleable parts.

Grey’s Downside series, unfolding in the historically freighted proxy-space of the mine, deploys the lexicon of horror in an analogous way: to signal and expose the violent concatenations and continuities of past and present. The Downside world is overseen by a shadowy government of sadistic, besuited ‘Management’ characters, emblematic of the privatising rise of the ‘country as company’, whose legislations take the form of hyper-capitalist imperatives to consume ‘to … quota’ and who preside over a rigorously stratified population, the classification of which recalls the artificial taxonomies of apartheid, but translates these into economic terms. For example, in The Mall (2011), the first novel in the series, Upsiders Rhoda and Dan encounter a radically uneven society of ‘Shoppers’ (p. 164), ‘Customer Care Officers’ (p. 165) and—most notably—‘Browns’ (p. 175), representative, respectively, of consumers, workers and a homeless, starving, scavenging demographic not formally incorporated into either of these categories, and which is evocative of Davis’s ‘surplus humanity’: that population relegated to conditions of acute vulnerability, in a world where stable employment and state support are equally elusive, and where the material prerequisites for life—land, water, food, sanitation—are rendered increasingly inaccessible through insistent privatisation.

The Mall, in which the whole world is—as the title suggests— precisely a shopping precinct, also registers especially clearly the post-apartheid decline in material production that is one key contributor to increasing and apparently irremediable unemployment in South Africa, and which in turn generates conditions of deep precariousness in the aftermath of democracy. The only workers present in the subterranean geography are ‘Customer Care Officers’, their designation as such exemplary of the sanitised corporate speak in which all Downsiders communicate, and whose exclusively immaterial labour testifies to an economy founded not on industry, but on the provision of services. The characterisation of these workers also frames this development as peculiarly violent, beginning to evidence the trilogy’s wider manipulation of horror for critical ends. Dan, for example, is inducted as a Customer Care Officer through a grisly ritual, in which a hole is bored into his skull: despite his urgent pleas for mercy ‘the drill goes in, smooth and hard, like a screwdriver into a rubber doll’ (p. 196). In the first instance, the cavity enables his literal plugging into the Downside ideology, with the result that he becomes a vacant-eyed ‘zombie’ (p. 207), who witters neoliberal mottos in the language of hard work, corporate ladders and ‘high-percentile sales’, all the while bleeding from the perforation in his head (p. 211). In the second, however, it also introduces into the narrative’s parodic restaging of post-apartheid unevenness a particular vision of the body as fleshy material, which is physically and thus emphatically vulnerable before the system in which it is placed. The same sense is reiterated in the characterisation of Shoppers, who reflect, with disturbing literality, Baudrillard’s comment that in the consumer society ‘bodies and objects’ become indistinguishable from one another. Shoppers are hypostatised flesh, interpreted in commodity terms as ‘depreciat[ing]’ entities (p. 204): the women are ‘starved and bleached and blue veined to hell’ (p. 215), and men have ‘skin [that] strains over pecs and abs … too defined to be real’, and which is covered in the ‘criss cross scars’ of surgical reconstruction (p. 199). Modifications proliferate in the novel, becoming increasingly more bizarre: cranial bone grafts, implants forced under the skin in unlikely places and a clefted chin into which can be fitted several fingers, all realised crudely and clumsily so that the signs of the scalpel and the saw remain visible.

On the one hand, Grey is clearly satirising a postmodern vision of identity, inherited from the likes of Baudrillard, and explored in horrific terms, by, for example, Bret Easton Ellis’s infamous Patrick Bateman, with his inability to differentiate between sentient bodies and the commodities he compulsively consumes. The hyper-objectified Shoppers materialise the construction and transmission of selfhood through commodity objects-signs, incarnating, with their complex artificial appendages, augmentations and extensions, the imperative to excess—reflective of the imperative to consume issued by the novel’s Management—that Botting identifies as a signature aesthetic in gothic fictions written under conditions of late capital. On the other hand, and more profoundly, however, the obvious corporeal violence etched on the consuming bodies of the Downside Shoppers participates in the trilogy’s wider investment in laying bare, by translating it into immediate and physical terms, the pervasive structural violence of macroeconomic neoliberalism as this operates in South Africa after the turn of the millennium.

This programme is especially evident in the second book in the series—The Ward (2012)—which is set in (and below) a state hospital, ironically named ‘New Hope’. The hospital is not hopeful. It is instead a grim indictment of post-apartheid government health care: it is filthy, overcrowded, understaffed, chaotic and filled with the desperately poor, for whom there is no alternative possibility for medical attention. This last is emphasised in the narrative, because Farrell—the protagonist—is not poor: he is young and successful, and, since he is covered by expensive private health insurance, only finds himself in New Hope—he believes—as the result of some kind of mix up following an accident. As it turns out, there is no mix up: Farrell is in New Hope because it is from this particular hospital that Downside operatives glean Upside inpatients, taking them below where they are marked as uncategorised Browns and given the ominous status of ‘Donor’ (p. 118). The cobbled-together appearance of the Shoppers that populate Grey’s subterranean mall now takes on a new, unpleasant significance: the elaborate distortions, extensions and artificial implants that signal the excesses of the Shopper class are revealed to originate, in a reactivation of Marx’s famous vampiric analogy for capital, in the bodies of unclassified Browns.

The scenario carries echoes of the practice, routine under apartheid as Nancy Scheper-Hughes points out, in which ‘human tissues and organs were harvested from black and mixed race bodies without the family’s knowledge or consent and transplanted into the bodies of more affluent white patients’. At the same, it bears traces of a black market for human organs in contemporary South Africa, which springs up, as the Comaroffs suggest, in response to circumstances of inexplicable and devastating degradation. The narrative is imprinted by these histories of biomedical exploitation and occult violence, but it also mobilises the scene of unwilled organ harvest metaphorically, translating contemporary conditions of material precariousness—indexed in the appalling presentation of the government hospital and reiterated as Farrell is coded as Brown within the Downside order—into immediate bodily vulnerability, shaped in the text with recourse to the setting and conventions of surgical horror. As he is situated on a gurney in the Downside theatre, a ‘Butcher’ standing over him, ready to extract ‘muscle, tissue, [and] bones’ (p. 255) for rehoming in the depreciating bodies of the economic elite, Farrell presents the novel’s category of ‘Brownness’ as what Foucault, in his work on biopolitics, figures as the disposable, indeed necessarily killable, body, whose death sustains the ‘species body’—makes it ‘healthier and purer’—of a particular population.

Biopower designates the ‘calculated management of life ’, a propagation effected through a set of ‘regulatory controls’ enacted through state institutions, of which the hospital is a pre-eminent example. However, as Foucault argues, it also structurally entails the production of a territory of death, in which are located all those bodies that if they were to remain alive might present ‘a threat to … the improvement of a species’. Biopolitics thus becomes a politics of death when, as in Farrell’s particular situation, death will benefit the population under biopower’s protection. And, as Foucault points out, death in the field of biopower should not be taken ‘to mean simply murder as such, but also every form of indirect murder: the fact of exposing someone to death, [and of] increasing the risk of death for some people’.91 As it approaches conditions of post-apartheid vulnerability through the topos of the government hospital, the narrative already raises questions about the uneven distribution of wealth and privilege in the biopolitical mode—questions that derive from the fact that ‘New Hope’ is presented precisely as a site at which life is exposed to death, and not one at which it is propagated. These circumstances are reiterated and emphasised in horrifying terms in the surgical procedures that take place Downside: Farrell’s fatal experience on the Butcher’s operating table translates what is framed in the novel’s upside world as Foucault’s ‘indirect murder’ into a ‘direct’ and active instance of killing. Because this is performed, furthermore, in the interest of a particular (horribly excessive) ‘species body’, it also situates the structural violences it condenses and emblematises within the biopolitical scene, linking them implicitly to another demographic, as the means through which that demographic’s health and security is assured. Thus the narrative presents a post-apartheid South Africa in which the exploitation and precariousness of certain demographics sustains the privilege and propagation of others: it draws on an excessive vocabulary horror to expose the violence of this structural unevenness, rendering it visible and palpable.

But the novels are not, as I have suggested, only invested in signalling the injurious effects of a post-apartheid agenda: their vision of violence is situated at the intersection of past and present, in the site where a neoliberal programme reanimates vulnerabilities cultivated under apartheid and its predecessors. Mbembe argues that apartheid’s own species of biopower emerges ‘par excellence’ in the mining compound, where black workers lived out their contracts as if prisoners serving ‘hard labour’. These institutions constituted ‘floating spots where “inhumanity” could be experienced in the body’ as a racialised subjection to surveillance and discipline. In the context of the mine, the body of the black worker ‘could be searched at the end of the shift … it could be stripped naked, required to jump over bars. Hair, nose, mouth, ears, or rectum could be scrutinised … Floggings with a sjambok … or tent rope, or striking with fists, were the rule.’94 The compound thus reveals the extent to which, on a scale grander than the parameters of the mine, apartheid produced a racialised biopolitical ‘state of exception’, in which black lives could be disproportionately exposed to death. As Grey’s narrative locates its millennial emblematisation of the biopolitical scene in the subterranean space of the gold mine, it invokes these earlier racialised exposures. They are the history over which the novel layers post-apartheid states of vulnerability, witnessed as the inadequacy of state support in New Hope, and as an insecurity linked to land, food and employment in the homeless, jobless demographic of Browns—a term which itself tells of a mutating inheritance. The designation is not deployed as a racial marker in the narratives, but only to signal a category of insecurity within the Downside order; and yet it carries with it the historical payload of the racist taxonomy that previously served officially to mark off protectable from killable life. Thus, the narratives translate into vivid scenes of active injury the asymmetries of privilege and precariousness effected through the deindustrialisation, privatisation and state retractions of the neoliberal programme, and they suggest the extent to which these processes reactivate and compound a history of cultivated exposure, conjuring this most decisively in the local gothic topos of Johannesburg’s mineral necropolis.

About the book

This is a new book, an original book. It traces the history of literary representations of violence and fear in South Africa, and it interrogates the ways in which these might be fruitfully considered as falling within the remit of ‘Gothic’. The reader will find here a vast range of texts; a continuing political commentary handled with subtlety and discrimination; and a sure hand when thinking through the postcolonial implications on Gothic tropes.

—Professor David Punter, University of Bristol

South African Gothic maps a complicated literary history, charting a course that is absorbing, engaging and insightful. Moving from Gordimer and Coetzee to Wicomb and Brink (as well as many others), Duncan reads Gothic narratives of diverse anxieties that emerge in the social, cultural and political transition from apartheid to democracy. Theoretically informed and well written, this book is an important intervention in Gothic literary studies.

—Professor Justin D Edwards, University of Stirling

The term ‘Gothic’ has rarely been brought to bear on contemporary South African fictions, appearing too fanciful for the often overtly political writing of apartheid and post-apartheid South Africa. As the first book-length exploration of Gothic impulses in South African literature, this volume accounts for the Gothic currents that run through South African imaginaries from the late-nineteenth century onwards. South African Gothic identifies an intensification in Gothic production that begins with the nascent decline of the apartheid state, and relates this to real anxieties that arise with the unfolding of social and political change. In the context of a South Africa unmaking and reshaping itself, Gothic emerges as a language for long-suppressed histories of violence, and for ongoing experiences at odds with utopian images of the new democracy. Its function is interrogative and ultimately creative: South African Gothic challenges narrow conceptions of the status quo to drive at alternative, less exclusionary visions.

About the author

Rebecca Duncan is Teaching Assistant in English Studies at Stirling University.