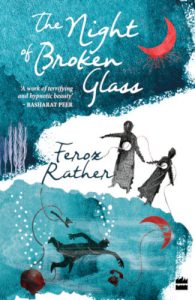

In his debut work of fiction, The Night of Broken Glass, Feroz Rather masterfully captures the peculiar, punctured lives of ordinary Kashmiri civilians living under an occupation, writes Azad Essa.

Feroz Rather

Feroz Rather

The Night of Broken Glass

HarperCollins, 2018

1.

Mist hangs over the boulevard. A young man driving a rickety car stops on a bridge. The car switches off. It stutters. He is shot dead. His father gathers his bullet-ridden pheran and takes it home as his last memory. More than a hundred kilometres away, another man is stopped by the army. His hands are tied. He is placed on the bonnet of a Jeep to prevent angry youth from pelting the army with stones. Back in the city, a writer dreams of Freedom. But he cannot find a job. He joins a PR firm writing press releases for the occupiers. A young man is tortured. He waits years to plan his revenge. He finds his oppressor old, sick and frail. He kills, not the man, but his revenge. A young girl looks out the window to watch the boys of the neighbouring village protest. Police fire teargas and shower the valley with lead pellets. She is hit. She falls. She wakes up blind. A university professor teaches poststructuralism. He is a PhD but feels suffocated as a citizen. He lowers the pen and picks up a gun. Less than forty hours later, he is shot dead.

2.

Some history.

In the seventeenth century, the Moghul emperor Jehangir travelled to Kashmir. He was so smitten by the rustic beauty of the valley, with its flowing brooks and expansive, opulent hills, he is said to have decreed, ‘If there is a heaven on earth, it’s here, it’s here, it’s here’.

The Kashmir Valley, nestled at the foothills of the Himalayas, was not just a spectacular find for the Moghuls, it was also a strategic one. With central Asia to the north and west, China to the east, and the Indian subcontinent to the south, Kashmir was uniquely poised at the edge of history. Today its language has hints of Farsi, its cuisine and fashion carries the history of the Turkic people, its mosques are broad-Buddhist-styled halls and its roofs are pyramidal, with Sino-inspired spires. Here, the Brahmin Hindus love their meat.

The Moghul occupation of Kashmir between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries was followed by the occupations of the Afghans, the Sikhs and the Dogras, Hindu rulers from the region of Jammu. The Muslim majority was now ruled by a Hindu king. In 1947, Kashmir found itself embroiled in the logic of religious division during Partition. It was eventually split between India and Pakistan after a war. At the cessation of hostilities, the United Nations declared that a referendum would be held for the people of Kashmir to determine their future. It never came, of course.

The Kashmir Valley, Jammu and Ladakh were taken by India, while Pakistan took a sliver of Kashmiri territory as well Gilgit and Baltistan. A third, mostly ignored section of Kashmir, known as Aksai Chin, later went to China’s Xinjiang province.

Since the late eighties, India-occupied Kashmir has been in the midst of an uprising. The armed rebellion, sponsored and supported in part by Pakistan, has seen India deploy more than 700,000 troops to the region. At least 60,000 people have been killed. Another 5,000 others are unaccounted for.

Today, India-occupied Kashmir is the most militarised place on earth.

3.

There is little consolation in knowing that Feroz Rather’s first book, The Night of Broken Glass is a work of fiction. The novel, a collection of interconnected short stories, reads like the literary equivalent of pulp, if such a genre were possible. The characters are grotesque, morally ambivalent and mesmerising. The scenarios are uncomfortable, wretched and damning. The stories stop, start, and never seem to end. Here the mosques are not exempt from fraught social hierarchies, here a poor cobbler resents his upwardly mobile son, here a shopkeeper is made to lick graffiti off his wall. In an upending of archetypes, martyrism is an ongoing conversation, not a preordained destination. ‘And how dare you think of paradise when Kashmir still exists on earth?’ Tarik asks Mohsin, as they lament in jail for throwing stones at an army convoy.

Short stories can be obnoxious: metaphors overused, the enforced austerity of words leading to flirtation with self-indulgence. But Rather’s collection has no such problem. His characters, as complex and disparate as they might be—cobblers, murderous army officers, stone pelters, estranged lovers, rebel fighters, fathers, mothers, girlfriends, boyfriends and delinquent ghosts—are tied in their individual stories inexorably to Kashmir’s collective destiny. Kashmir is very much the centre. As the author admitted in an interview about his book, this centrality could be a weakness. But fuck it, it is precisely the book’s strength. He masterfully captures the peculiar, punctured lives of ordinary Kashmiri civilians living under an occupation. It is distressing to read—and cathartic, I presume, for some. Hunted underdogs and tortured overlords will certainly relate.

The Kashmiri underclass sit at the place’s beating heart. The middle and upper classes are always ready to run to Delhi, selling Kashmere, Cashmere, Kashmir—however they wish to spell their identity, their culture, art and food. But the working class are bound by vast tentacles of the occupation. Their story is Kashmir’s: told in tales of upper class villainy and the opportunism of the political and religious elite. Rather’s book glides and startles as it navigates the contradictions, without ever losing sight of Freedom’s pursuit. This is a land of multiple oppressions and occupations. There is no beginning, middle or end. There are no perfect victims; and though the perpetrators of violence may be depraved, they aren’t perfect villains either. Rather cuts through tropes and cobbles together a hardly believable but vehemently real society, vulnerable and scarred.

As in real life, the characters do not reconcile with their crises. They stand. They fight. They perish. The stories are furious, restless and intimate. Where the novel falls short is in its perpetuation of the male gaze throughout, even when its seeks to explore sexual harassment by a rebel fighter or an Indian soldier. The female characters, as resilient as they might be, are almost always sexualised.

4.

Rarely in the past decade has a month gone by without at least a week’s worth of disruption in Kashmir. This is a land where life stands still. Nothing seems to ever get done. Today counter-terror forces closed off Dal Lake for a search operation. On Thursday, four untrained rebels were shot in a forest near Tral; one body was dragged through the streets. On Tuesday, five girls were blinded outside their school in Srinagar by lead pellets. Three of them will never see again. On Friday, the internet services are cut in downtown Srinagar because of protests outside the Jamia Masjid. Two boys from poor families and an unemployed old man are taken to hospital. A journalist interviews a rebel fighter and gets a call from Delhi; on his arrival he is held without charge. The day after, a house is burnt down in Pulwama because the old lady who lives there was seen feeding rebels fresh bread. A boy breaks curfew to feed pigeons at the Shah-e-Hamadan shrine. He is stopped by police, given a chance to feed the birds and then handed a gun. He is told to open fire at the birds pecking at the rice on the plaza. ‘Good shot … now bring go fetch the hunt,’ he is told. On Wednesday, boys throw stones at police because the old lady from Pulwama died, and are shot at with pellets and tear gas. A nineteen-month-old baby suffocates from chilli gas shot outside the family house. Her father, a doctor, rescues her. On Monday, a school in a town in the south is closed and converted into a bunker because the rebels were seen in the town on Thursday.

In The Night of Broken Glass, beauty and betrayal sit like shards of ice depriving mountain goats of treats on hill tops; like lotus stems conspiring with weeds to suffocate Dal Lake; like damp paddy fields that, at a whim, quite easily overflow and flood.

- Azad Essa is a journalist based in New York City. Follow him on Twitter.