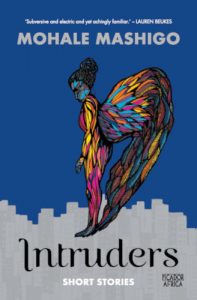

The JRB presents ‘Afrofuturism: Ayashis’ Amateki’, an essay by Mohale Mashigo, which serves as the preface to her new collection of short stories, Intruders.

Intruders

Mohale Mashigo

Picador Africa, 2018

Afrofuturism: Ayashis’ Amateki

Speculative Fiction that addresses African–American themes and addresses African–American concerns in the context of twentieth-century technoculture—and, more generally, African–American signification that appropriates images of technology and a prosthetically enhanced future—might, for want of a better term, be called ‘Afrofuturism’.

—Mark Dery, from Black to the Future: Interviews with Samuel R Delany, Greg Tate and Tricia Rose

This collection would be incomplete for me if I didn’t include stories set in ‘the future’. Writing it, I could almost feel Afrofuturism hiding in the shadows, waiting for the right moment to shout, ‘pick me’. It is all the rage right now and everybody has his and her own idea of what it is—even when it’s some misguided marketing weirdo just wanting to connect with the cool kids (gross).

There are stories that take place in the future but cannot strictly be called Afrofuturism because (I am of the opinion) Afrofuturism is not for Africans living in Africa. This is not meant, in any way, to undermine the importance of Afrofuturism. So why even mention this? Well, it’s probably because South Africa is a country that suffers from low self-esteem and too often parrots the United Kingdom and United States of America (hi, Cultural Imperialism)—just hang out in Braamfontein and listen to people talking about ‘peng sneakers this, that and the other, bruv’. This is not an indictment on a world that is shrinking (thanks, in part, to social media) or on the laaities (I’m in my mid-thirties, so I feel I’ve earned the right to call them that)—I love young people and am often in need of a Youth Concierge (a term coined by my writing partner, Nomali Minenhle Cele, who is too young and enjoys making fun of my ‘elderly ways’; it means a young person who helps an ‘older’ person understand technology, new slang and trends).

I believe Africans, living in Africa, need something entirely different from Afrofuturism. I’m not going to coin a phrase but please feel free to do so. Our needs, when it comes to imagining futures, or even reimagining a fantasy present, are different from elsewhere on the globe; we actually live on this continent, as opposed to using it as a costume or a stage to play out our ideas. We need a project that predicts (it is fiction after all) Africa’s future ‘postcolonialism’; this will be divergent for each country on the continent because colonialism (and apartheid) affected us in unique (but sometimes similar) ways. In South Africa, for instance, there needs to exist a place in our imaginations that is the opposite of our present reality where a small minority owns most of the land and lives better lives than the rest.

I don’t think I should, at this time in our history, be involved in a lot of talking and dreaming about the beautiful skies and the moon, and so on, and dreaming about ideal situations when we don’t have them. In the very first place I wouldn’t have taken to writing. I wouldn’t stick to it when it is so difficult. Except for the fact that I see in it some kind of exposure: it gives me the opportunity to expose what we feel inside.

—Miriam Tlali, interviewed by Cecily Lockett, 4 September 1988

This was my particular challenge when writing stories based in the future. I’m not a fan of dystopia (though sometimes it feels like we are living it) nor am I a believer in utopia; but I do believe that there is a place in between the two where South Africans are able to live in a future that is free from white supremacy (please don’t argue with me; I’m not interested in your reverse racism fallacy) and poverty. For me, imagining a future where our languages and cultures are working with technology for us in order to, as Miriam Tlali says, ‘expose what we feel inside’, I had to draw from South African folklore and urban legends. How could I not go back to our amazing stories about mutlanyana (rabbit) outsmarting a hungry lion, for inspiration? Or ‘jazz up’ urban legends: the headless horse named Waar is my Kop (Where is my Head) that terrorises young children, or the beautiful ghost of a young woman named Vera who haunted the roads of Soweto at night, causing young men to drive off the road?

It was much easier for me to lace up takkies that were familiar and, indeed, ‘my size’, in order to travel a road unknown. Is the future still filled with (generational) inequality? Are there any smart cities or has corruption stolen the opportunities for young people to influence the direction of technology? If resources and education currently benefit only one group, what does that mean for the use of technology in the future? How does who we are right now affect an imagined future? These are questions that I’m interested in. I’m also interested in who we are now, no matter how unremarkable we seem, under the lens of speculative fiction.

Afrofuturism is an escape for those who find themselves in the minority and divorced or violently removed from their African roots, so they imagine a ‘black future’ where they aren’t a minority and are able to marry their culture with technology. That is a very important story and it means a lot to many people. There are so many wonderful writers from the diaspora dealing with those feelings or complexities that it would be insincere of me to parrot what they are doing.

My story, as an African living in Africa, is this: I lived (as in, under the same roof ) with white people for the first time when I was a nineteen-year-old student. My television screen showed stories populated by black people speaking indigenous languages, so I have never suffered from a lack of representation as such. Was I, though, still living in a country where my culture, language and presence were considered a nuisance? Absolutely!

We are so used to wearing shoes that don’t fit us—the shoes that are often so tight that we even stop calling them by their familiar, colloquial names—’di bhathu’ or ‘takkies’—and give them a new name adopted from elsewhere. So we walk around with fake swagger, trying to hide that we are wearing sneakers that aren’t made for our feet.

In the nineteen-eighties South Africa had a genre of popular music called Bubblegum music. One of my Bubblegum heroes was Mercy Pakela, who had a hit song called ‘Ayashis’ Amateki’—a song about a pair of shoes that was beautiful but too tight for her. The chorus is ‘Ayashis’ Amateki, this is not my size’. ‘Ayashis’ Amateki’, loosely translated, means the shoes (in this case takkies—what we now call trainers or sneakers in South Africa) are burning my feet—because they are too tight. I wonder sometimes if Mercy Pakela wasn’t really a philosopher who was trying, with her hit song, to tell us to remain true to ourselves.

It would be disingenuous of me to take Afrofuturism wholesale and pretend that it is ‘my size’. What I want for Africans living in Africa is to imagine a future in their storytelling that deals with issues that are unique to us. I would like for us to see what size takkies fit us, and run with that. It’s obviously too late for me to bring takkies ‘back’ (most of my family still call them that) for cool kids but perhaps there is enough time to stop us from adopting other things that aren’t necessarily for us. Whatever you do, do not go and call it something obnoxious like ‘Motherland Futurism’—asseblief tog!

May this ____________ (insert the name you’ve all agreed on) also focus on Now and not just The Future. Let us use our folktales if need be—use them to imagine us being fantastical in this Africa we occupy right now. I write for a comic book, Kwezi, and I cannot tell you how happy it makes children to see a superhero who looks like them and lives in a country like theirs. Let us be fantastical* right now and in the future, wearing takkies that fit us.

* fantastical (adj.): conceived or appearing as if conceived by an unrestrained imagination; odd and remarkable; bizarre; grotesque.

- Mohale Mashigo is the author of the bestselling novel The Yearning, which won the University of Johannesburg Debut Prize, as well as Beyond the River, a Young Adult adaptation of the movie of the same name. She is an award-winning singer, songwriter and writer for the Kwezi series. Her new book, Intruders, is out now. Follow her on Twitter.

I feel the cultural pride and guardianship in her comments. I think there are two things that she is addressing. First Science fiction is for everyone. Futurism is stories about tomorrow, the next day or year. Five years or five million years. Thinking about the future is just dreaming which leads to planning. As an African American I always feel that I am American because we didn’t get our calculations right about Arabs and Europeans.

Second, I think that all futurism is important because it allows you to see what other cultures are thinking about.

I don’t know that it is fair to say that afrofuturism is for those who are divorced from their African roots. I have always felt that it is more about moving beyond past stereotypes and problems flowing from the legacy of colonialism. Thus, black people who are tired of seeing themselves depicted as the conquered (whether that be through subjugation or slavery) can imagine a future in which their people are powerful, have institutions that are strong and meaningful, and have some kind of agency to shape the world around them. In Black Panther, for example, the villain was a member of the diaspora. His diaspora story did not represent the future, as important as that experience was. It was clearly shown to be the past, as was established in the closing scenes of the movie where the Wakandan people seek to provide a future by shoring up institutions of knowledge. It seemed to me that the story wasn’t really about Killmonger connecting with his roots, but about a fantastical non-colonized African nation deciding to use its power to strengthen institutions serving black people outside of their nation and share their agency with those people. In sum, the comment I think implied that afrofuturism is about reaching back (to ones roots) in some way, when I think it is about reaching forward based on new institutions and agency that all people of African ancestry can aspire to.

Today, as a consequence of historical circumstances, Africans are scattered around the planet. As obvious as this may be, it is worth stating that Africans are therefore plural, i.e., we have continental Africans as well as Africans from outside the continent. Members of both sub-groups live both on the continent and abroad. How our africanness , i.e, the very shared African heritage, itself is lived and felt, is clearly informed by our specific material and social conditions of existence. In that sense the existence of nuances in how our very africanness is understood and shaped is to be expected. I appreciate the present paper as a recognition that while African agency is on the whole to be cherished, local differences are not only unavoidable, but most importantly, must be celebrated lest our common heritage becomes a straight jacket!

Wow, I didn’t perceive the concept of Afrofuturism this way before – although creative, it does not tackle real issues like white supremacy within African nations. I was wondering if you could recommend fiction books that tackle at least some ‘future post-colonialism’? I need to do a book review for a University project.

I want to know what the author has read or been through to make her feel so deeply that the African perspective is not welcome or celebrated in spaces of Afro futurism. Did someone uninvite this sister to the party?

I for one want her to know that the Diaspora experience and the African experience are not unrelated nor unrelatable to eachother. They in fact have communicated and informed each other across intended seperation for centuries.

If the voice she wants to write in is uniquely African there’s great value in that.

You made a good point that African fiction should deal with issues that matter to Africans. I’m currently doing research about the science fiction genre and I think it would be interesting to include a section about afrofuturism in my paper because a recent superhero movie has brought the idea at the forefront of the mainstream. Perhaps I should start looking for African fiction book publishers and see if there are works that may be considered as adjacent to science fiction when it comes to African literature.