By recentering the narrative on Durban and Natal, rather than Johannesburg and the Transvaal, Jon Soske modifies the established account of Struggle history, writes Alex Lichtenstein.

Internal Frontiers: African Nationalism and the Indian Diaspora in Twentieth-Century South Africa

Jon Soske

Wits Press, 2018

1.

The complex relationship between Africans and Indians in South Africa has always been a particularly ambivalent one. There is no question that Indians proved stalwarts of the liberation movement in every conceivable sector: witness the activism of Yusuf Dadoo, Monty Naicker, Fatima Meer, Ahmed Kathrada, Saths Cooper and Jay Naidoo, to call out but a few. On the other hand, as Ashwin Desai and Goolam Vahed have previously argued, Gandhiji himself, who lived for twenty-one years in the colonies that ultimately came to form part of South Africa—from 1893 to 1914—seemed perfectly willing to advance the fortunes of Indians at the expense of Africans.

As Jon Soske puts it in Internal Frontiers, his ambitious re-examination of this relationship through the lens of nationalism and anti-apartheid resistance, the Mahatma’s ‘struggle to obtain rights for Indians as British subjects endorsed the colonial racial order’. Lest we imagine Indians confined this sort of racial special pleading to the days pre-1910 (the year the Union of South Africa came into being), one need only look to Indian Opinion in the early apartheid era. An editorial in April 1950, penned by Gandhi’s son Manilal Gandhi, counseled Africans to ‘first concentrate not on criticising the Government or the oppressors but on changing their way of life’. Soske acknowledges that Gandhi moderated his views after he quit South Africa for India; all the same, he assesses the Gandhian legacy as one that ‘helped to cement a conservative tradition in [Indian] diasporic politics and a rhetoric of Indian civilisational superiority’ that the more militant postwar generation of South African Indian Congress (SAIC) activists like Dadoo and Naicker struggled to overcome.

These tensions were not merely organic; the common oppressors of Africans and Indians, the colonial and then apartheid states, did much to fan existing tensions between the two communities. But there was always plenty of kindling to work with. If I may be permitted an analogy, the African-Indian relationship looks much like the Black-Jewish relationship in the United States. Subject to similar—if sharply differentiated in intensity—racism and discrimination, American Blacks and Jews often worked together to eliminate racial prejudice. At the same time, urban African-Americans often resented Jews, who found themselves structurally playing the role of petty exploiters of their Black neighbours and compatriots—as shopkeepers, landlords and competitors for restricted urban residential and commercial space. This allowed demagogues like Louis Farrakhan of the Nation of Islam to cloak anti-Semitism in the fiery language of Black nationalism, using local resentment against Jews to whip up his political base, in much the same way that EFF commander-in-chief Julius Malema did with his recent diatribes against South Africans of Indian descent. Strikingly, as Soske observes, the central narrative trope of the ‘Indian’ in Africa is that of the ‘merchant’, a figure who ‘pursued economic interests through duplicitous means’—a racial discourse that persists in post-apartheid South Africa, notwithstanding its sociological inaccuracy.

And then there was 1949, which really has no exact parallel in the United States: Internal Frontiers devotes an entire chapter to the anti-Indian pogrom that broke out in Durban in January that year. The previous decades of rapid urbanisation and industrialisation had created an urban social geography in which ‘Indians and Africans of all classes lived among and adjacent to one another’, Soske points out, with the former often holding the upper hand, especially in their dealings with recent Zulu migrants from Natal’s rural hinterland. As Soske puts it, in the immediate postwar years ‘the Indian came to exemplify the dependent position of the African within a series of spaces that governed core aspects of daily life’ in urban Natal, primarily as shopkeepers and landlords (and sometimes as employers).

Unlike those he writes about, Soske wisely avoids reifying racial categories (especially in his discussion of the Durban Riots), noting that in fact they overlaid multiple affinities and interests that potentially paved the way for a different kind inter-communal politics in Natal. If, for example, most Africans could relate to the discourse of ‘Indian domination’ in their daily lives, this reflected the ‘lived experience’ of only a very small number of Indians themselves. Still, the unusual proximity of Indian and African urban communities in Durban produced a particularly virulent form of ‘anti-Indian populism’ among African residents, one that exploded in the killings of 1949. Merchants trading in Grey Street (now renamed Dr Yusuf Dadoo Street) may have been the initial target, but the violence soon spread to working-class communities like Cato Manor, where Africans both attacked and protected their Indian neighbours. Africans, one witness told a commission investigating the riots, ‘deeply resented the fact that they now had to “serve two masters”, one white, one Indian’. The 1949 riots, widely underappreciated in a South African historiography concerned with white/Black conflicts, prompted ANC intellectuals to ‘rethink the relationship between African nationalism and a broader South African identity’, as Soske demonstrates.

2.

Along with Partition in the subcontinent, the Durban Riots demonstrated ‘the dangers inherent to the demand for national self-determination’ within multiracial states, Soske notes. At the same time, the Passive Resistance Campaign led by a cohort of young Indian militants in Natal against Jan Smuts’s infamous 1946 Asiatic Land Tenure and Indian Representation Act—known as the ‘Ghetto Act’—stirred the imagination of African activists. In concert with the Indian anticolonial struggle, the emboldened Indian Congress helped draw both AB Xuma and the Africanists of the ANC Youth League into the orbit of international struggles for national self-determination. After World War II, the new nation of India embodied such aspirations, and Jawaharlal Nehru, its first Prime Minister, brought the plight of South African Indians before the newly founded United Nations Organisation, indicting South African racism on the world stage for the first time.

For an Africanist like Anton Lembede, this orientation proved inadequate to overcome a distrust of ‘foreigners’—Indians—and internationalists, like those in the Communist Party (CP), and Soske concludes that Lembede’s African nationalism, at least, remained rooted in the ethno-particularism typical of Western thought. Nor did the Youth League initially abandon anti-Indian rhetoric in the immediate postwar moment. ‘Many Africans,’ Soske observes, ‘worried that a sovereign India would strengthen the position of South Africa’s Indians to their increasing detriment.’

It was the visceral violence of the Durban Riots that ultimately enabled Youth Leaguers such as Oliver Tambo, Walter Sisulu, AP Mda and Jordan Ngubane to ‘rethink the form of the liberation struggle’ and the nature of African nationalism in the new South African context, and soon thereafter to seek a delicate rapprochement with the Indian leadership. For their part, the SAIC, refusing to acknowledge African grievances, insisted that whites had instigated the 1949 violence to divide opposition to apartheid; this rather put the cart before the horse. Unity was the result, not the cause, of the Durban Riots. Ordinary Indians, however, embraced a narrative of ‘African savagery’, entrenching a longstanding distrust of their African neighbours, while their African counterparts sought to enforce a mass boycott of Indian-owned shops.

Both communities, Soske points out, mobilised gender as foundational to national self-identity, and thus regarded ‘interracial sexual intimacy as corrosive’. African men resented what they decried as Indian ‘seduction’ of African women; Indians, in turn, defended ‘Indian tradition’ as embodied in the female domestic sphere—another urban privilege allowed Indians but denied Africans. If the latter complained of Indian men’s encroachment on their sexual territory, the former insisted that their own commitment to ‘racial purity’ made such behavior unthinkable. Those ANC and SAIC leaders who sought to bridge this divide thus confronted a ‘subaltern nationalism’ that fused anti-communism, resentment of Indians, and defense of female virtue.

Soske’s exemplar of a leader able to transcend these conflicts is Chief Albert Lutuli (popularly spelled ‘Luthuli’). In his joint leadership of the 1952 Defiance Campaign, alongside Indian comrades, Lutuli created ‘an iconography and vocabulary of struggle centred on the African-Indian alliance’. Lutuli and those who shared his commitment to Afro-Asian solidarity faced significant opposition from below, as some Africans remained tempted to embrace aspects of apartheid, which would, after all, remove Indians from African areas. Yet, under Lutuli’s leadership, the diasporic politics of Indian anticolonialism came into dialogue with the ANC’s nationalism to forge a ‘new aesthetic of nationhood’, one that created ‘the image of a multiracial African nation’ to be. Lutuli drew on his deep Christian ethics, and his experience ‘living and actively participating in local communities’ surrounding the Groutville mission reserve in Natal, to envision an inclusive, democratic African nationalism. The 1955 Congress of the People in Kliptown (though not the Freedom Charter that resulted) stands as fullest expression of Lutuli’s nationalist ethics, Soske suggests. Above all, Internal Frontiers, demonstrates the centrality of the ‘Indian Question’ to the forging of an open and pluralistic African nationalism.

As Soske observes, most histories of the early anti-apartheid movement focus on the battle within the ANC between the non-racialism preached by the Communist Party and the Africanism that came to fruition with the breakaway of the Pan-Africanist Congress in the late nineteen-fifties. By recentering the narrative on Durban and Natal, rather than Johannesburg and the Transvaal, Soske modifies this account of Struggle history. In Natal, the ‘Indian Question’ retained a signal importance in the forging of nationalist politics that it simply did not elsewhere in South Africa. That said, perhaps Soske overstates the difference between the Natal group’s ‘ethical vision of a multiracial African nation’ and the non-racialism generated by the ‘aspirational civic nationalism’ associated with CP/ANC rapprochement, a development Soske regards as championing a blunter African majoritarian ideal of nationalism.

Still, Internal Frontiers deepens and enriches historically contingent debates about the nature of nationalism within South African liberation politics prior to Sharpeville and the turn to armed struggle. For example, it allows Soske to emphasise the degree to which Indian anti-colonialism during the late nineteen-forties came to infuse the ANC’s own nationalist politics, and thus transformed the ANC’s relationship with the SAIC (and other elements of the Congress Alliance). The resulting ‘Natal synthesis’, as Soske calls it, enabled Lutuli to advance a pluralistic nationalist ideal, embodied in the isiZulu phrase ‘kulelizwe siyizizwe eziningi’—a nation composed of many nations—best captured by the Congress Alliance’s symbol of a spoked wheel. Soske insists that the ‘National Democratic Revolution’, as articulated by the CP/ANC alliance during the period of armed struggle, largely eclipsed this more pluralistic tradition, which was only revivified by the Mass Democratic Movement of anti-apartheid’s endgame. But is the ‘production of a common identity through the African liberation struggle’ associated with the ‘Natal synthesis’ quite so distinct from the nonracial alternative, or is this merely hair-splitting?

3.

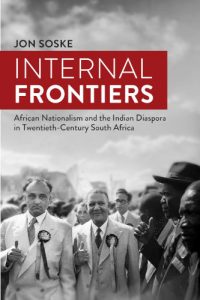

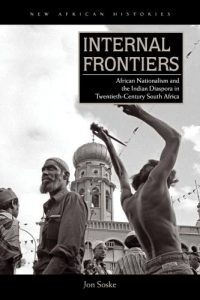

Interestingly enough, the cover of the South African and American editions of this book differ considerably. The former sports an early Jurgen Schadeberg photo of Yusuf Dadoo and ANC leader JS Moroka side by side during a 1952 Defiance Campaign protest, surely one of the high points of Indian-African cooperation against unjust laws. By contrast, the US edition (published by Ohio University Press) offers a powerful photograph by veteran Struggle photographer Omar Badsha of an Indian celebration of the life of a Sufi saint in front of Grey Street’s Juma Masjid, one of the largest mosques in the southern hemisphere. One shouldn’t read too much into such editorial decisions, which may reflect nothing more than, for example, difficulty in securing and paying for image permissions, or the differing book cover tastes of different markets. Nevertheless, the photo of Dadoo and Moroka suggests the ability of Indians and Africans to forge common struggle, while Badsha’s photograph is a reminder of the relative ability of Indians to establish urban communal and cultural institutions not initially available to Africans in the apartheid city.

Interestingly enough, the cover of the South African and American editions of this book differ considerably. The former sports an early Jurgen Schadeberg photo of Yusuf Dadoo and ANC leader JS Moroka side by side during a 1952 Defiance Campaign protest, surely one of the high points of Indian-African cooperation against unjust laws. By contrast, the US edition (published by Ohio University Press) offers a powerful photograph by veteran Struggle photographer Omar Badsha of an Indian celebration of the life of a Sufi saint in front of Grey Street’s Juma Masjid, one of the largest mosques in the southern hemisphere. One shouldn’t read too much into such editorial decisions, which may reflect nothing more than, for example, difficulty in securing and paying for image permissions, or the differing book cover tastes of different markets. Nevertheless, the photo of Dadoo and Moroka suggests the ability of Indians and Africans to forge common struggle, while Badsha’s photograph is a reminder of the relative ability of Indians to establish urban communal and cultural institutions not initially available to Africans in the apartheid city.

Internal Frontiers offers an account of a novel form of African nationalism that seeks to merge two visions of common bonds and communal self-expression in a new, more hopeful form of synthesis. Soske concludes grimly, not to say controversially, that ‘these ideals are dead within South Africa’s ruling party’, with racial chauvinism the predictable result. Forged at a crucial moment in the anti-apartheid struggle, perhaps such a nationalist synthesis may be revived, in a cosmopolitan, far more democratic South Africa, for a way forward in our own perilous times.

- Alex Lichtenstein, a frequent contributor to the LA Review of Books, teaches South African and US history at Indiana University and is editor of the American Historical Review. Follow the AHR on Twitter.