Torn for so long between anxiety and awe at the idolisation of Nelson Mandela, The JRB Contributing Editor Bongani Madondo approached his latest book of letters with trepidation, only to be uplifted by Mandela’s scorching vulnerability.

1.

Dated 31 August 1970Letter to Makgatho Mandela: His son

Heit My Bla

I don’t know whether I should address you as son, mninawa or, as we would say in the lingo, my sweet brigade.—Page 191, The Prison Letters of Nelson Mandela

2.

Dated 23 June 1969Letter to Zenani and Zindzi: His daughters with Winnie Mandela

My Darlings

Perhaps never again will Mummy and Daddy join you in House No 8115 Orlando West, the one place in the whole world that is so dear to our hearts.—Page 106, The Prison Letters of Nelson Mandela

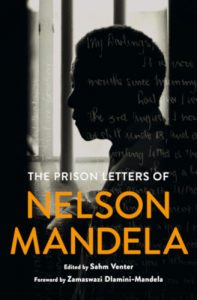

The Prison Letters of Nelson Mandela

The Prison Letters of Nelson Mandela

Sahm Venter

Penguin Random House, 2018

1.

Like our latter-day, digital-insta neediness—over-sharing, over-confessing, over-fishing for ‘likes’ and red-hued mini hearts—the art of letter writing was, at its most basic, an earnest but not always honest means of reaching out to the world. In other words, letter writing was a personal, and, in the supplest of hands, an artistic quest to create a sense of community, through the grace and showmanship necessitated by the form.

The era of letter writing—from 1995 backwards, now lost forever—demanded a different set of conditions for the act of creation: solitude, ink bleeding in cutely handcrafted script on to the pages, the ‘writer’ burdened with the anxiety of filling too many of them, which folded together might not fit into a specific-sized envelope. Envelopes too, as carriers: subject to their own economies, which of course affected not just the length of their contents, but also the frequency that the would-be letter practitioner, letter romantic, could write.

The project of letter writing, then: tactile, performative, urgent, questing, desperate and—depending on the occasion—sometimes one of crafting lullabies with hand-quilted scripts, in a fashion redolent of craft, to win a target’s affections. It was the closest thing to broadcasting your seal of style: your most personal yearnings expressed in the most singular combination of gestures, tones and colours.

Perhaps because of the cruel and inhumane confinement that he and his comrades were subjected to for close to three decades, or simply because of the need to mobilise, reach out to people and express himself, or because he was separated from his wife and children too early, and the soul-wrenching way it happened, or all of the above, Ol’ Dalibunga drew sustenance from writing letters.

In addition to the now well-established multimillion-dollar cottage industry of Mandela Literature (itself part of a humongous global Madibanomics enterprise lorded over by warring legal eagles, family, foundations, publishing houses, copyright raiders, snake-fat salesmen and the like), a sub-genre of Madiba archival literature is emerging, which is inherently limited: his prison letters.

This new hardback collection, The Prison Letters of Nelson Mandela, published by Penguin Random House and edited by Sahm Venter, with a foreword by Zamaswazi Dlamini-Mandela, hit the shelves on the eve of the global centenary celebrations of the man and his legacy. As a concept, the book should not stir up too much excitement—mainly because it is not the first collection of Ol’ Dalibunga’s personal letters. In 2010, Pan Macmillan published Conversations with Myself, with a foreword by Barack Obama (the closest heir to the spirit amalgam of Mandela and Martin Luther King the twenty-first century has thus far produced) and so, speaking flippantly or even with a dose of self-righteousness, Prison Letters does not immediately evoke a sense of discovery, a whiff of newness or a promise of revelation. The aforementioned Conversations, and to an extent Winnie Madikizela-Mandela’s 491 Days: Prisoner Number 1323/69 (Pan Macmillan, 2013), are at heart personal testimonies and private correspondences issuing out of, or heading back into, prison. So the Mandela letters literary market—racket?—should by rights be over-traded. No so?

Prison: the anti-home away from home. But, also, a space for organising otherwise rampant, roaming thoughts. Through meditative routine, sheer endurance or implacable indifference to outside luxury, poets, prose writers and activists have made the most of their situations in prison. Some of the most inspired prison writings—The Man Died: Prison Notes of Wole Soyinka, as well as the diaries of Kofi Awoonor, Sanyika Shakur (aka Kody Scott), Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, Wally Serote, among others—have shown how prohibitively small spaces and the concomitant curtailing of movements—the physical and psychological lockdown of all your faculties—can be escaped, if only through the flight of the mind.

Finally, prison is also a place, as Mandela’s letter writing project over three decades illustrates, where the most fertile and determined of freedom-seeking souls can escape at will, even while their bodies are locked inside their cells and forced into demeaning menial labour, also known as the state’s legalised slavery.

2.

As per the book’s inside flap: Prison Letters is organised chronologically and segmented into the four venues in which Nelson Mandela was held as a sentenced prisoner. It begins in Pretoria Local Prison, where Mandela was held following the 1962 Rivonia Trial. In 1964, he was taken to Robben Island, ‘where a stark existence was lightened only by visits and letters from family’. Then, to Pollsmoor Prison in Cape Town’s southern suburbs, where Mandela and a few of his comrades were held in rooftop cells, separate from the larger population of inmates, and finally to Victor Verster Prison, which was clearly a preparatory holding space and provided some kind of re-induction into the social and cultural fabric of the late nineteen-eighties. This for a man who was intermittently jailed in the late nineteen-fifties and early nineteen-sixties until his final capture, trial and twenty-seven year stretch.

Not that Mandela, before Victor Verster, was totally in the dark about the outside world. If there’s any inmate who, despite spiritually debilitating circumstances, was looked after while inside and treated with utmost respect—and indeed with less fear than, say, the likes of Robert Sobukwe and Jafta Masemola, who inspired pathological levels of that emotion in their captors—then Mandela was that prisoner. But much about his time in prison, his rising above circumstances, is well known. Indeed, so much has been written about Mandela that it seems impossible to unlock fresh water from the boulder to quench our thirst for new insights. This collection is accordingly not exempt from the weight of history and the dullness of too much information, too much knowingness, when it comes to his life.

And yet … and yet. There is something about its editing, patient archival organisation (dates, full names, nicknames, glossary), original facsimile copies of yellowing and tattered letters and, ultimately, narrative sequencing. There is something here.

Editor Sahm Venter, a veteran of the Mandela archive (housed at the Nelson Mandela Foundation, whose blessing this book necessarily bears), has over the years developed an extra pair of ears for the voluble in Madiba’s most vulnerable silences and whispers. Her experience is discernible in the manner which she hauls over an archival project and renders it into a curiosity-piquing literary assemblage. She intrinsically understands the patience and scholarship it takes to balance the whimsical and the tragic, or separate the fantasy from the realism in a subject’s perpetual self-documentation and (re)writing. With this project, Venter and Dlamini-Mandela (Mandela’s granddaughter, a young woman proving to be her family’s literary custodian) have pulled off quite a risky but ultimately worthy literary trapeze act, which doubles as a vital legacy project.

The book is brimful of Mandela in bloom, in pain, in defiance. Mandela the patriarch dad hoping—at some point seemingly succeeding—to govern his home from the confines of his cell. Mandela the traditionalist invested and well versed in the rural affairs and cultural customs of his native Eastern Cape, then known as ‘The Colony’. Steadily, starting from one of the first letters Mandela wrote, to Mr. L. Blom Cooper of Amnesty (International), dated 06 November 1962, while Mandela was still on trial, through to the mid-nineteen-seventies and early-nineteen-eighties era of intense black uprisings, something emerges here. Mandela the friend, charmer, dad, brother-in-law, student of life, reader, political strategist: ultimately the book reveals a distinctly unheroic, distinctly vulnerable person. A spirit tearing at the seams but never detached. A soul that is aware of the pitfalls of giving up. A self-assembling persona that understands its freedom and the freedom of its people, as Mandela himself wrote in the famous letter to his then-teenage daughter Zindzi, which she read in Soweto in 1985, ‘cannot be separated’.

Nelson Mandela scholars and the broader Mandela literary ‘hive’, as it were, will be familiar with some of these texts. For example, half of the section entitled ‘Family Correspondence’—themed ‘Arras’ in Conversations—is carried here again without blushes. The book gets away with it, largely, because both books are products of the same archive, and unlike the essay or straight biography, letters remain pretty much the same from work to work. In a literary context, they are their own players and referees.

I found them touching and deeply poetic.

I also felt quite guilty, traipsing around the Madiba interiority map like a trespasser in the witching hour, stealing into another person’s most personal, most anguished, most optimistic and ultimately most self-liberating space. I felt it an invasive act reading, for example, of the harrowing, helpless attempts (and failures) at gluing his family together—the need to be a presence in absentia, a magical feat that would test the most accomplished conjurer.

The guilt I felt, though, could not pry me away from feasting on the most personal of Mandela’s writings.

3.

I perused, ferreted, longed and even yearned for them. Biography addicts are zealots, but collected letters fans are a niche and notch lower: we are scavengers of the soul; we lust, insatiable voyeurs.

In letter after letter to Winnie Mandela, and to daughters from Makaziwe to Zindzi—especially upon hearing the news of his first-born son Thembekile’s death in the spring of 1969—the dad/husband opens up, drawing the reader into his taut language, which, however, does not do much to hide a soul on the edge of total wilt. And yet, like a stubborn spring flower, he refuses to wilt. Instead, he seems to gain strength with each letter. No matter that a truck-load of of them do not ever reach their destinations; no matter that they are spied upon, censored, desecrated—or kept in pristine conditions, safe in some apartheid apparatchik’s vault.

In this book, Winnie Mandela, once again—no surprise—morphs into a central character: in fact, she is internalised and reimagined as different characters in one—almost a reversal of Njabulo Ndebele’s Homeric The Cry of Winnie Mandela (New Africa Books, 2003). Finding himself aflutter between hero-worshipping Winnie, in total exultation at her strength and militant resolve, in her caregiving skills and role as anchor of the family, and total frustration at his own immobility, especially in those moments Winnie herself is subject to lengthy imprisonments, Mandela breaks into heart-piercing arias, calling her: Dadewethu, Comrade, Mentor, Hero, Sister, Love of My Life, and Nobandla, Mhlope and Zami.

Constructed through his pen, Winnie is not really waiting—pace Ndebele’s Penelope-Winnie—for Mandela at all. Her hands, heart, soul and house are brimful. She’s on the move, she is everywoman. And yet a piece of her belongs to him and him alone, even though the struggle of her people, his people, has all but consumed her.

In Mandela’s letters, Winnie is the African spirit-alternate in Nina Simone’s ‘Four Women’.

In this song, from the 1966 album Wild Is the Wind, recorded in the midst of the Civil Rights struggle in America, Simone created a sonic-theatrical tableau inhabited by four women. Four seemingly different women—but who might possibly be the same mutating spirit, y’know. There is ‘Aunt Sarah’, who portrays the abuse and resilience within and against slavery. Pain is inflicted on her again and again. The second character, Saffronia—think of Toni Morrison’s singular and feisty Sula, a woman in control of her body and desires, even as she was rendered eccentric, a pariah; and think, too, of Gabo Márquez’s Remedios the Beauty from One Hundred Years of Solitude, a woman who lived in her head so much that one day she took off and floated up in the sky, never to return. She is also, possibly, a product of the systemic rape and abuse of the African woman by Europeans’ ‘civilising’ power. The third character is that of a woman who is in command of her sexual capital and so no one but herself will determine her currency.

The last—the climax of both the narrative and the music on to which this Negroid and Negri-tudinal socio-cultural spectacle takes place—is Peaches. We are told she is embittered and hardened by generations of enslavement (but that might be disempowering an otherwise radical spirit). I take her name and what she represents as Sankofa, the resilient Akan and Asante symbolical bird simultaneously expressive of the past and the future: Roots and Futurism. Peaches is, in a way, the song’s freest, or at least most freeing character, just by the manner through which Simone screams her name.

These women’s narratives, of course, cannot be taken literally, but they are well-known characters in our metafictions and hyper-realities. Parts of them are to be found in Alice Walker’s The Color Purple, and if you read Winnie Mandela’s out of print Part of My Soul Went with Him (Norton, 1985) or Anne Marie du Preez Bezdrob’s well-researched work Winnie Mandela: A Life (Zebra, 2004)—gallantly denounced as the work of a ‘white woman’ in this very publication, by a fledgling critic I respect but disagree with on that specific characterisation [Editor’s note: see ‘Banishing the white gaze‘ in The JRB’s May issue]—a certain lyrical formation emerges, stylistically variant but each an alter-Negro of the other. Four shape-shifting Winnies.

Viewed and appreciated as the sum total of these mutative spirits stirred out of the belly of some oracular power, you too can pick and choose which Winnie you are comfortable with, from the vast catalogue of Madiba’s references to her. You, too, can have your own Winnie Mandela. Besides, by acceding to the public archiving and consequent publishing of his personal letters, Nelson Mandela is inviting us to share what he had, what he longed for, what he could no longer control, perhaps never did. Perhaps his only mastery, as the letters imply, was the mastery of politics.

4.

For me, beyond Nina Simone, reading Madiba’s letters, his invocation of ‘uDadewethu’, also recalls two very different songs of Busi Mhlongo’s: ‘Ntandane’ and ‘Awukho Umuzi Ongena Inkulumo’. Of course, Mandela did not have the aforementioned blues soul sisters in mind when writing to his wife. To him, Winnie ceased to be only that, a wife, and became everything a man and his struggle, a nation and its struggle, a family and its pillar-constantly-chipped-at, represented. It was too much on her—as later, contested revisionist interpretations have shown following her death in April.

This book is a compendium of Nelson Mandela’s letters and not a Winnie Mandela anthology, so I am quite alive to the fact that it remains exactly that. But at the heart of the book and the man’s life, till his very last breath on Earth, is the fire and passion with which he loved her, and found solace in her, and you read with slowly sinking heart as he tiptoed on the brink of total breakdown:

DadeWethu 01st ??? 1970

Can it be said that you did not receive my letter of July 01? How can I explain your strange silence at a time that you had been confined to bed for 2 months & that your condition was so bad that you did not appear with your friends when your case came up for remand.

He wonders, almost in soliloquy:

Is your silence due to a worsening of your health or did the July letter suffer the fate of the 39 monthly letters, letters in lieu of visits & specials that I have written since your arrest on May 12, ’69, all of which, save 2, seemed not to have reached their destination?

Often, as happens within letter writing to familiar people such as family and friends, formalities give way to coded intimacies understood by the writer/speaker/sender and the recipient(s) alone. In this and other letters, however, Mandela tosses off formalities left and right. But mind you, it is 1970, and he was in his early fifties, and almost a decade in the dungeons. Despite this, his writing hints at an oncoming, poststructuralist, avant-garde black prose-poetry, such as Lesego Rampolokeng’s punky-reggae style, where children are ‘chdn’ and year is ‘yr’ and emotional pain is ‘rough & fierce’. He was committed to fighting with all his might, take on any internal, elemental battle, just to alleviate his all-purpose wife/comrade/sister/mentor’s own prison blues:

The crop of miseries we have harvested from the heartbreaking frustrations of the last 15 months are not likely to fade away easily from the mind. I feel as if I have been soaked in gall, every part of me, my flesh, bloodstream, bone & soul, so bitter am I to be completely powerless to help you in the rough & fierce ordeals you are going through.

Winnie is not the only recipient of his barrage of words, charm and warmth. She is his all-abiding love, but he treats other women comrades, such as Adelaide Tambo, Albertina Sisulu, his biographer Fatima Meer and Mamphela Ramphele with a Neruda-esque pumping energy. To Ramphele he writes:

A train of staggering coincidences hit Victor Verster after your visit, so much that I have since wondered whether coincidences are coincidences.

By the late nineteen-eighties his handwriting has become denser, much more carefully scripted, quite affirmed, strong and visually more structured and beautiful. His brief, simple and pregnant-with-wisdom-and-love letter to Walter Sisulu’s nephew and niece, Len and Beryl Simelane (02 November 1989, written on the cusp of his release), is testament that writing, the art of physically writing—not quite as a literary response or an expression of artistic impulse—can be just as gorgeous as advanced doodling with paint or organising clean lines within a frame of minimalism.

I do not imagine that was Nelson Mandela’s intent, of course. He and hundreds of other imprisoned men and women—imprisoned in physical structures and psychic gaols—knew too well that the collective push-back against their people’s dehumanisation was a matter of life and death. And yet, in those silences and amidst the screams, people’s individual traits, cadences, quirks, beauty and longing emerged. While we can never ever be congenially grateful for Mandela and the PAC, or the Black Consciousness and Communist activists, we should be grateful that Mandela had the presence of mind to write out multiple biographies in shards and fractions of brilliance, resolve and vulnerability. It is out of these letters that a more flesh-and-blood Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela, Ol’ Dalibunga, emerges.

Reading this I begin to hunger for other prisoner’s letters. Who has the complete archive of Sobukwe’s letters? Was he even allowed to write and receive?

- Contributing Editor Bongani Madondo is a writer in residence at Wits Institute for Social and Economic Research (WiSER). He is also, with Professor Reynaldo Anderson, the co-curator of the first international symposium on Afrofuturism in Africa, due in October.