Nthikeng Mohlele honours South African National Poet Laureate Keorapetse ‘Bra Willie’ Kgositsile, who passed away in January.

A Person of Incalculable Value: A Tribute to Professor Keorapetse Kgositsile

Life-changing events of near-sacredness, so rare, are often triggered and sustained, even granted immortality, by a meeting of human beings. It is often and erroneously taken for granted that human beings are created equal—and it is also often overlooked that such equality is distinguished by varying degrees of greatness.

Such was my meeting and subsequent friendship with my recently departed mentor and artistic anchor point, the man I simply referred to as Prof, the late Keorapetse Kgositsile, fondly known as Bra Willie.

2001 seems a long time ago now—that moment that endowed my art, and the art of others, my seniors, my contemporaries, with a depth, quality and range that will echo across the continents for a long time to come.

His telephone number was and remains recorded in my mobile gadget simply as, ‘Poet Laureate’—two words that connected me to ideas, to vigorous reflection, to feather-light yet concrete guidance, to history, to laughter and to camaraderie. Those five-minute, nineteen-minute and sometimes two-hour telephone exchanges were and remain deeply prized to me. Those wide-ranging yet laser-beam-focused personal reflections on the Civil Rights Movement; on the rise, meanings and contradictions of nationalism; on the waves of independence that washed across the African continent; on the cross-pollinations of music—big band and swing jazz—between America and Sophiatown. Medgar Wiley Evers. Detroit Red—Malcolm X—whom Prof fondly and casually referred to as ‘Malcolm’, as in, ‘Malcolm found me sitting, reading the newspaper. He was exhausted, and I think he had the flu.’ I would never have thought one of the greatest orators, thinkers and political visionaries of the twentieth century suffered silly and irritating things like the flu. An important detail.

That was and is the power of Prof: to humanise otherwise mythical people, to reduce complex sociopolitical trends and established theoretical frames of reference to punchy and insightful one- or two-liners—typically beginning with his favourite points of entry: ‘In fact …’ ‘You have just reminded me …’ ‘Exactly!’ ‘Remember, this was the nineteen-sixties …’ Or his warmth upon answering the phone, saying, ‘Hey Monna, Nthikeng, I was just thinking about you …’

The Bra Willie I knew, loved and respected—the one I revered because he commanded both greatness and unfaltering grace, both integrity and humour—was a multifaceted soul: Poet with a capital ‘P’; a rigorous and fearless thinker; a scholar; an unsentimental and informed critic of the arts; a seasoned conversationalist with penetrating insight, modesty and an ever-present smile. Many facets and dimensions of this lighthouse of humanity and culture are yet to be discovered and embraced, to inspire years after the king has taken his bow of mortality.

Just as some men are equal in the spiritual and existential sense, it is worth recording that some human beings have lived such productive, inspirational, disciplined, generous, selfless and brave lives that they have in a sense earned the privilege of eclipsing death. Given the plurality and significance of his achievements, as artist, teacher and, simply, as a very fine human being, Prof is one of these people.

It is proper to feel overwhelmed and to grieve because of your passing, Prof—but also to feel lucky to have shared both the wonderful and not-so-wonderful things life is made of, is known and rumoured to possess, with you. It is fitting to zoom in and illuminate my personal experience of Prof as teacher, so gifted and full of exactitudes that he taught me lessons that would otherwise have taken my entire life to learn. The power of proper use of punctuation, for instance. And what literature isn’t and must not be: an abuse of artistic gifts for self-promotion, vain inanities, recklessness or aesthetic dictatorship. That literature was pointless without a social vision of rebellion and a quest for redress, without moral meditation and agency. That there is temperament and responsibility to perspective; that thoughts without self criticism are nothing but erratic demagoguery.

How does one say farewell to a fountain? How possible is it to enumerate the reach of a teacher who teaches you not only the technical tools of literature and writing, but who is kind, enlightened, caring and equipped to demystify, not only the purpose but the inherent contradictions of art in the theatre of life, in all its dimensions and manifestations? And to do so with pronounced and polished intensity or restraint, when specific social circumstances or the level of understanding of the student so required? To be that attuned to helping impressionable people connect the dots?

My last conversation with Professor Kgositsile in person was at the Abantu Book Festival in December of 2017—a conversation that has grown profound qualities and tentacles of epiphany for me. I asked Prof how he was, and he cited fatigue and ill health in a by-the-way kind of tone. I then said to him that I wanted to grant him one hundred more years of earthly life because I (we, that is, artists as well as other people working in other disciplines) still needed him; because he had so much to still share. There was that signature grin. The brushing of the sage’s beard with an open palm. He then said: People who do not want to or are afraid to die are those that have not lived their lives or done what they are supposed to do.

In hindsight, I now know what he meant.

Farewell, my friend. Go well, my teacher. The artistic seeds entrusted to me and my generation are yet to fully bloom.

Finally, the path of a departing Poet, of so great and dazzling a human being, can only be partially lit by the throbs of prose, so:

In the turbulent high seas

Of art & life

Infested with pirates pests and saints

In the sandstorms of time memory & being

The glaciers and avalanches of

weightlessness so rare

Is a ship captained by a King

A King robed in black and gold

A man slight yet celestial

With eyes that saw above and beyond

Ears that heard raindrops form

Sink we shall not

For our King is awake

Prompt & already at shore

To rinse sand and salt off our feet

For a walk into eternity

With grace and a little

Silence.

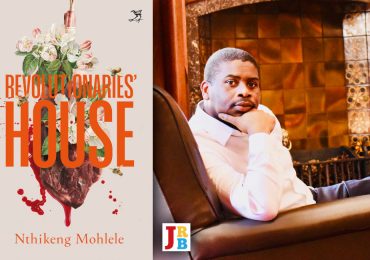

- Nthikeng Mohlele, who sits on The JRB Editorial Advisory Panel, is the author of four novels: The Scent of Bliss, Small Things, which was translated into Swedish as Joburg Blues, Rusty Bell, and Pleasure. Mohlele was listed by Bloomsbury Publishing, the Hay Festival and the Rainbow Book Club among the 39 most promising authors under the age of 40 from sub-Saharan Africa and the diaspora. He lives and works in Johannesburg.