Nelson Mandela altered the world. He affected everyone in it, in ways few will ever manage. He also died before wrapping up a book about his period governing South Africa. In Dare Not Linger, award-winning author and poet Mandla Langa finishes this book, preserving Madiba’s voice intact. Contributing Editor Bongani Madondo speaks to the author about channeling Madiba.

In real life we deal, not with gods, but with ordinary humans like ourselves: men and women who are full of contradictions, who are stable and fickle, strong and weak, famous and infamous.

—President Nelson MandelaBy offering this full portrait [Long Walk to Freedom], Nelson Mandela reminds us that he has not been a perfect man. Like all of us, he has his flaws. But it is precisely those imperfections that should inspire each and every one of us.

—President Barack Obama

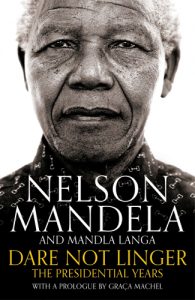

Dare Not Linger: The Presidential Years

Dare Not Linger: The Presidential Years

Nelson Mandela and Mandla Langa

Pan Macmillan, 2017

Recalling the emotion, the thick atmosphere surrounding Nelson Mandela’s first post-prison-release address to the heaving, chaotic and anticipative multitudes milling around Cape Town’s Grand Parade, the Release Mandela Committee’s communications man Saki Macozoma—a gifted scribe in his own right—writes:

After much drama Madiba made it to the balcony of the City Hall. The light was fading. Cyril [Ramaphosa] had to hold a lamp for him to be able to see the words of his speech.

The speech closed with a pledge, in Xhosa: ‘Ubomi bam busezandleni zenu (My life is in your hands).’ In the fading light Madiba read it as ‘Ubomi bam busedlanzeni zenu’, which is a corruption of the original saying.

And thus ended a momentous day with the marshals shepherding the crowds home and ensuring that not a single incident of vandalism of violence marred the reception of our leader …

From that day until today, remembers Macozoma, Madiba’s life was ‘in the hands of the people of South Africa’.

Although for most of the perilous three decades of his incarceration—alongside a host of other political prisoners from across a myriad black liberation formations—Mandela’s life was in the hands of his captors, to generations on the outside it was lodged in a sacred nook deep within our hearts. While he was uncertain about his island situation, our love and veneration for him and his struggle cohort—Walter Sisulu, Ahmed Kathrada, Govan Mbeki, right across party political bickering and schisms—was assured. We all know what ensued in the weeks, months and years before the historic and long-awaited 1994 elections, wherein Mandela and his party, as expected, swept the scores and won in a landslide. The transition period between Mandela’s release in February 1990 and his inauguration on 27 April 1994 has been documented to a pulp, including in Mandela’s bestselling memoir, Long Walk to Freedom.

What, until now, has not been comprehensively narrated, analysed and viewed with the benefit of time and distance—at least as understood and lived by the man himself—is Mandela’s dual first term as president of both the African National Congress and the country.

Mandela’s coxcombic personality and public branding—a traditionalist who enjoyed dapper attire; an Africanist elder in Thai shirts; an empathetic man but unforgiving upon discovering Winnie Mandela’s well-reported romantic peccadilloes, the result of nearly three decades of piercing loneliness; a Western-style democrat in awe of African royalty—rendered him an irreducibly complex spirit. In consequence, there has been an avalanche of books on him, by authors trying to lay their inky fingers on the soul of the man.

Take for example ‘I Am Prepared to Die’, his heralded Rivonia Trial speech, in which, in full traditional-African regalia, he proclaimed, ‘I have fought against white domination, and I have fought against black domination …’—and which has since, not incorrectly, drawn black folks’ incredulity. Which ‘black domination’ was he speaking of, in the nineteen-sixties?

And yet Mandela’s charm and mystique always occupied an exalted space in our hearts. French left intellectual and activist Régis Debray refers to the veneration of the personnage médiatique, a flesh-and-blood man who is also a political talent and visionary, so gifted and empathetic that he is ultimately elevated to the status of a saint.

It happened to Mandela. So pervasive was that narrative thrust—mainly a creation of the liberal media establishment—in fact, that Mandela the person came across as a blurred, if not surreal, meta-figure, somewhere between a human being and magical creature of light. Which, of course, inspired the subtitle of my first book, Hot Type: Artists, Icons and God-figurines. Mandela being ‘God-figurine’-in-chief.

He died on 5 December 2013. Four years later, and two months before the party to which he devoted most of his life will hold its most divisive elective conference ever, Pan Macmillan has released the much-anticipated account Mandela himself wrote—but could not finish, owing to ailments and old age—detailing his complex time as South Africa’s first democratically-elected president. With Dare Not Linger, seasoned and award-winning author Mandla Langa neatly shapes Mandela’s handwritten notes (of up to 70 000 words, in book-publishing parlance), historical archives, and verbal and written contributions by Mandela’s widow Graça Machel and his speechwriting duo, Joel Netshitenzhe and Tony Trew, into a deeply rich, reflective and ultimately ghostly book. In Dare Not Linger, Mandela, once again, speaks to us.

The years describe a journey which, this time around, feels like both South Africa’s and the world’s, post- the Berlin Wall’s crumbling, post- the Soviet empire’s fall, post-Reaganomics and, at least in his home country, post- the debilitating state-sponsored violence that threatened to rip our future apart at its tender seams. It feels as though this was all in one man’s hands: the hands of Rolihlahla ‘Nelson’ Mandela.

Although not always his blind follower (in fact often a quarrelsome observer, appreciating from a distance), I was humbled to be given the chance to interview Mandela’s co-author, the man who brought his last testament to fruition, Mandla Langa, a week before the book dropped. Langa is the award-winning author of, among others, the novels The Lost Colours of the Chameleon and The Texture of Shadows, and an account of guerrilla warfare against the apartheid state, A Rainbow on the Paper Sky.

Bongani Madondo for The JRB: What was in your head when you were tasked to work on this project, at least from a literary and intellectual perspective?

Mandla Langa: It was a daunting but exhilarating task. Every writer enjoys a challenge that plunges him or her into uncharted waters. I had to dig deep and explore different literary devices to make a story of a great and iconic leader ‘tellable’. The new buzzword is ‘erasure’ and it is my belief that great people, especially if they stand for ideals that are inimical to the interests of the powerful, are erased via misinterpretation. They have to conform to certain ideas that others hold.

For instance, commentators like the late Stephen Ellis went to great lengths to remove political agency from black leaders. Oliver Tambo and Nelson Mandela, according to him, could not have had the requisite intellectual capacity to wage a struggle against white supremacist regimes. They had to be pawns of Communists, who were white and came from Moscow. The new erasure, favoured by soi-disant revolutionaries and guilt-ridden transgressors, is depicting Mandela as an irredeemable softie, a reconciliation junkie—an image equally pleasing to people about to commit crimes in the name of blackness and those who committed (and continue to commit) crimes in the name of whiteness.

At the outset, I remembered James Baldwin’s comment on Diana Ross’s performance when she played the role of Billie Holiday in the film Lady Sings the Blues. Rather than imitate Lady Day, Diana Ross paid homage to her spirit and beauty, her triumph in the face of insurmountable odds. ‘Diana Ross,’ Baldwin wrote, ‘clearly, respected Billie too much to try to imitate her. She picks up on Billie’s beat, and, for the rest, uses herself, with a moving humility and candour, to create a portrait’. It is my belief that in accepting Mandela in all his complex configurations, we can start coming to terms with the kind of greatness we are collectively capable of reaching.

The JRB: How does it work, finishing off a book by an author who is not around to approve the finished product?

Mandla Langa: Mandela was probably one of the most ‘unconfused’ leaders on the planet and had a clear understanding of who he was. A person like that, in a hypothetical case in which he’d have to posthumously approve a work about himself, would have been as philosophical as he was when we showed him his likeness at Madame Tussauds in the early nineteen-nineties, when he came to visit the United Kingdom. I was still working as the Deputy Chief Representative of the ANC in the UK. He looked at the image, which was not unflattering, and gave his hearty chuckle, putting all of us at ease. He’d have quickly sussed if there were malice aforethought on the part of the writer or sculptor and reacted to that exigency. In my case it wasn’t to help put together a hagiography; it was to continue the train of his thoughts, a task achieved, I hope, through the corroboration of historical documents, archives and the testimonies of his compatriots.

The JRB: I gather that he had already written in excess of 70,000 words. To others that’s a book on its own. What prompted the need for an additional author?

Mandla Langa: Important and insightful as the 70,000-plus words were, they had to be put within the frame of history and rendered capable of telling a story. That’s where I came in.

The JRB: I find the book quite weirdly told, in a beautiful yet surprising fashion: I was expecting it to be in the first person, the voice of Mandela. Indeed his voice in the book is unmistakable, but the narrative reads like a combination of Mandela’s recorded speech and a friend’s retelling of his late confrères’ stories. What informed the narrative approach?

Mandla Langa: The brief was to ensure that Mandela’s voice shone through in the book, and I believe it does; mine was to amplify the voice through the contextualising material, archives, testimonies, and so on, rather like a traditional melody enhanced by the introduction of contrapuntal voices and instrumentation. Bearing in mind that the book is a chronicle of Mandela’s presidential years—notwithstanding my own orientation as a novelist—there was no way to avoid the reportorial tone and the preoccupation with creating a verifiable account.

The JRB: On more than one occasion the book (I can’t quite pinpoint where Mandela’s voice ends and yours begins) cites the Velvet Revolution leader, poet and later free Czech Republic President Václav Havel’s adage about ‘destiny’ in a way that suggests Mandela was not only destined to lead the country but had internalised this and was ready for the task prior to the transition period. Yet elsewhere, in the section titled ‘Getting Into the Union Buildings’, Mandela is shown as being initially ambivalent about the prospect of becoming the president. Is this a reflection of a humble soul or an indecisive politician?

Mandla Langa: I think all of us should agree that ‘destiny’ simply means the overwhelming concatenation of events and circumstances that impinge on a person and drive him in a certain direction, where certain choices are inevitable. If you’re strong willed and sufficiently courageous, and if, then, you encounter circumstances inimical to your sense of self or justice, you’re likely to react the way Mandela reacted to the tragedy that was South Africa, mostly in the way he did. The adage, ‘cometh the hour, cometh the man’ (or woman), is the most immediate elision of destiny. In circumstances where that man or woman turns into a monster, society, which bears some responsibility for the ascension of that monster to power, is duty-bound to bring that monster down.

On his reluctance—or ambivalence—about taking up the mantle of office, Mandela had merely wanted to embed stability and lay the foundations for democracy, before handing the baton over to the men and women who would use bricks and mortar to fortify the democratic house. But he was also aware of how he was regarded by society, as the man with the requisite authority to ease society into the new territory. Remember, he had read many of the books on difficult political transitions then prevalent, and he needed to ensure that South Africans avoided civil war.

The JRB: In the chapter ‘Traditional Leadership and Democracy’ we witness an insight not analogous with the ‘radicalised’ millennial’s public perception of Mandela as a politician who was elusive on race matters. Earlier on during his governing years, he addresses Parliament on the violence in KwaZulu-Natal, and I’m pulling this specific line out of its broader context: ‘The perception that whites in this country do not care for black lives is there. I may not share it but it is there.’

Do you think he really did not share this sentiment?

Mandla Langa: I don’t think Mandela would callously downplay the feelings of the majority of black people about the fact that whites were seen to be uncaring about black lives. It must be remembered that Mandela went to prison exactly for fighting a system that dehumanised black people and his every utterance must be backgrounded by his statements, especially his speech at the dock. My take is that he was somewhat impatient with the focus on race at a time when action was needed, especially in KwaZulu-Natal where fratricidal strife was happening, albeit as a consequence of white state machinations. He may have been reflecting a frustration with the factious wrangling among black parties that had the (un)intended effect of benefiting and sustaining white power.

The JRB: In hindsight, do you think Mandela prioritised his reconciliation project over addressing lingering black pain and inequality?

Mandla Langa: Mandela believed that the project of reconciliation, which had been sanctioned by the ANC, would defang the right wing and engender a stable democracy that would enable an environment where the ‘lingering black pain and inequality’ would be addressed. It is inconceivable that reconciliation would be one man’s fetish alone.

The JRB: Not to make too fine a point about it, but Madiba sounds both miffed and reconciliatory, distraught and understanding, in that complex manner that only he (before there was an Obama!) could pull off. Do you think it fair that he should assume that his clearly highly evolved personal, political and psychic pragmatism, and visionary genius—all those rare and unique sets of attributes—would be shared and felt by the physically- and spiritually-bludgeoned majority? Was that not presumptuous of a leader, to corral the nation and people into his set of aspirations instead of, say, vice versa?

Mandla Langa: The South Africa of that time, which we now tend to examine with today’s eyes, was an extremely different—if not dangerous—place. The country needed authoritative, focused and moral leadership to coax it out of an impending storm.

The JRB: How would the Mandela of Long Walk to Freedom, Conversations with Myself and Dare Not Linger react to the current South Africa of ‘state capture’, ‘white monopoly capital’, and Fees and Rhodes Must Fall, and to the current battle for leadership raging within the ANC?

Mandla Langa: Mandela believed in the supremacy of the Constitution and held that people are motivated by good intentions. The hysterical confusion gripping South Africa today is an indication of an illness that afflicts a leaderless people: the paradox is that the wretched of the earth, despite all the revolutionary jargon, will become more wretched. In the Preface to Dare Not Linger, Mandela warns leaders who ally themselves to powerful and moneyed forces; he further enjoins leaders to listen to voices that might be critical of them.

The JRB: A few years ago, over coffee, I believe it was in 2011 or thereabouts, you and I got to talking intensely about Nelson Mandela—as we are wont to, given an opportunity—and you mentioned to me a work-in-progress essay in which you were seeking to draw parallels between Nelson Mandela and the postbellum ‘Negro’ leader Booker T Washington. What are the shared traits between the two?

Mandla Langa: In a nutshell, both leaders kicked against the orthodoxy of their own parties while waging battle against the bigger threat of racism and intolerance sponsored by their respective states. They shared an unshakeable belief in the rightness of their own convictions. They were also selfless. Today we forget that the South Africa of the nineteen-fifties in which Mandela became a Volunteer-in-Chief in the Defiance Campaign Against Unjust Laws was a period where to be black and politically motivated was to sign one’s death warrant. Ditto with Booker T Washington, who lived in the heyday of lynch mobs where, as a poet wrote, black flesh was sweet to the palates of police dogs.

The JRB: Working with Mandela’s notes, chapters, personal and state archives and in conversations with his colleagues and family members such as Joel Netshitenzhe, Tony Trew, Barbara Masekela and Graça Machel, as well as with the Nelson Mandela Foundation, how would you describe the role and impact of family on both ‘Mandela the leader’ and ‘Mandela the icon’?

Mandla Langa: Mandela always lamented the intrusion of politics and public commitments on his family life. There are moving passages that reference the loneliness suffered by all those who had been his family members, the funerals of his kith and kin that he couldn’t attend. It was this that made him cherish family life and could have contributed to his insistence on the one-term presidency; he used his iconic image to wrest whatever he could from the philanthropists at home and abroad, not for himself, but for the charities he supported.

- Bongani Madondo is Contributing Editor. His collection of essays, Sigh, the Beloved Country, was shortlisted for the University of Johannesburg Prize for South African Writing in English: Main Prize. He is an Associate Researcher at the Wits Institute for Social and Economic Research (WiSER).

One thought on “Linger No More: Mandela speaks from the grave, and Bongani Madondo speaks to his medium, author Mandla Langa”