Johannesburg is a city that dances on the edges of elusive, and yet somehow Santu Mofokeng managed to contain it within a frame, writes guest City Editor Lidudumalingani.

Photography is a kind of writing, but instead of a pen, the photographer writes with light, holding a camera and harnessing light into the frame to shape the narrative they want to create.

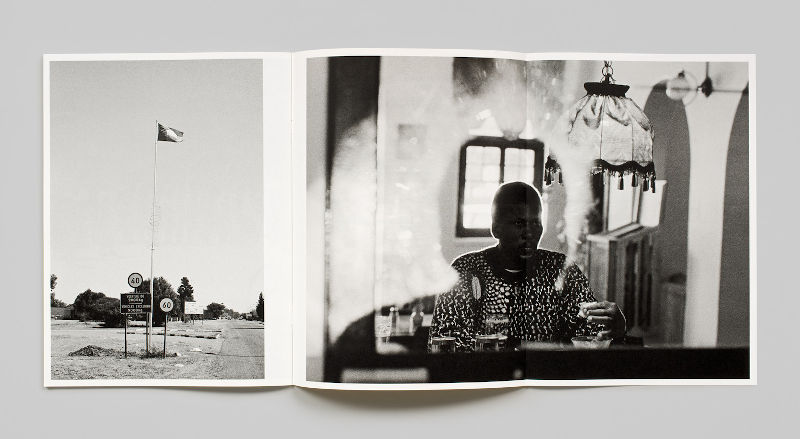

Santu Mofokeng, the legendary news and documentary photographer who passed away on the 27th of last month, aged sixty-three, persistently avoided the light. Where other photographers sought it out, he looked away from it, finding shadows instead, conjuring his images out of darkness.

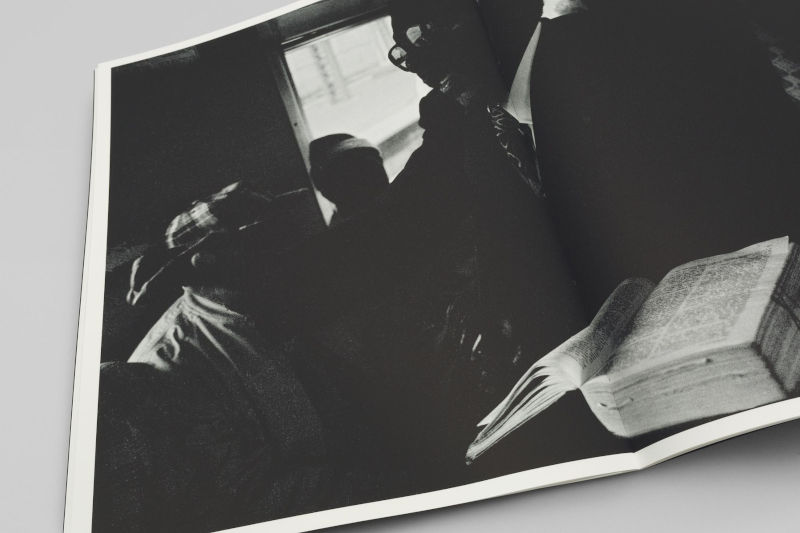

In the shadows, Mofokeng barely opened the aperture of his lens, allowing very little light to come in, and so his images don’t quite become photographs—instead, they are in every way spiritual, frames in transcendence. At first, they look imperfect—one may be tempted to suggest that had Mofokeng gone one F-stop lower, the result would have been better—but that is exactly his design, to court the darkness. In some other timeline, one could see Mofokeng nodding to Gordon Willis, the cinematographer whose use of low-light led him to be known as the ‘Prince of Darkness’. But Mofokeng photographed something far beyond the gloom. His subjects weren’t merely figures in the shadows, in the blur: they were subjects in another dimension.

In his series ‘Train Church’, made in 1986, when he was just thirty years old, a body of work that captures the spontaneous worship that took place during his commute on the Soweto–Johannesburg trains, Mofokeng captures the spiritual, the elusive. Johannesburg is a city that dances on the edges of elusive: the city at this moment is not the same as the city of the last. It is an amoeba, ever changing its form, its texture, and yet somehow Mofokeng manages to contain it within a frame. Mofokeng described the series, perfectly, as capturing the ‘two most significant features of South African life: the experience of migrancy and the pervasiveness of spirituality’. Perhaps pervasiveness is exactly what the blur in the details captures. Perhaps not. Perhaps the pervasiveness refers to the spiritual.

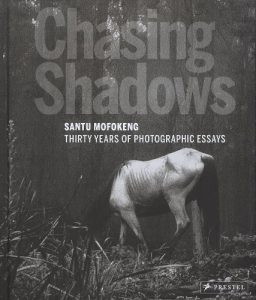

Mofokeng grew up under the thumb of apartheid, taking up photography in his teens, years he recalls in detail in his monograph, Chasing Shadows. He recounts how he lent his camera to someone and never got it back, and so when the riots of 1976 broke out he could not take photographs. An agony for a photographer, having to watch history slip by, unable to make a record of it. But even with that gaping hole, Mofokeng’s career is abundantly decorated. He worked for various magazines and newspapers, before joining the anti-apartheid Afrapix Collective in 1985, and for over ten years worked at the African Studies Institute’s Oral History Project at Wits University, where he discovered his talent for writing. In 1991, through an Ernest Cole Scholarship, Mofokeng studied at the International Center of Photography in New York, where he met the incomparable Roy DeCarava. These two men captured places that were geographically miles apart—Johannesburg and Harlem—in a kindred spirit, neither feeling it necessary to contextualise their photographs. Their meeting was orchestrated by the gods long before they were born.

Mofokeng’s images, blurry and dark, purposefully hard to make out, are not meant to capture the mundane. He chose to aspire to capture, instead, South Africa’s complexities. In an image he made in 1996, titled ‘Easter Sunday Church Service‘, a haze of smoke obscures the subjects, so that they appear as stubs, with only those in the foreground being clear. He assumed that people would know what other people looked like, but that perhaps what they did not know was what bodies looked like in spiritual flight, taken over by something beyond them—a state only achievable in another dimension.

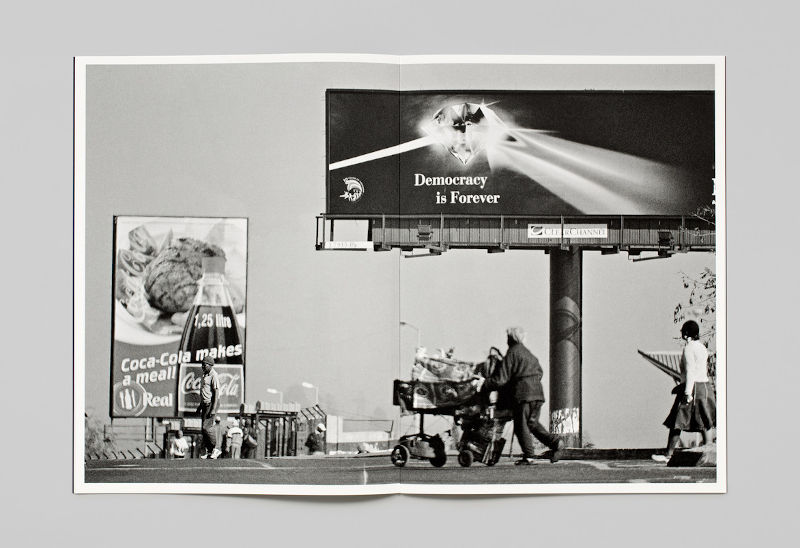

When Mofokeng worked as a photo-journalist, he took pictures of almost everything, from funerals, to parties, to churches, to street scenes. In all of these images and different contexts, as he writes in Chasing Shadows, he is there, in the shadows; not yelling instructions at his subjects, but nestled in the moment, in the details that emerge from the darkness. He writes that he could never work at the pace that newsrooms required and so would always turn his photographs in late. This is easy to track in his work: there is an aching search for something more elusive than linear story, clear details, tones and movement.

Of the many images that are being made in Johannesburg every day, by its throngs of photographers and citizens, none will ever capture the elusiveness of the city, its spirituality and its complexities, the way his photographs did.

Later in his life, when Mofokeng fell ill, he began to move more slowly, aided by his wife, Boitumelo, and then he passed on. I like to believe Santu Mofokeng ascended into heaven, into the perfect shadows out of which he made photographs, with his arms held up in a blur, letting it be known that he has come home, to a place of spirituality, the very thing he spent his entire life photographing.

- Lidudumalingani is a writer, filmmaker and photographer, and winner of the 2016 Caine Prize. Follow him on Instagram and Twitter.