Sean Jacobs reviews Slow Poison by Mahmood Mamdani, a rich and textured account of Ugandan and postcolonial African politics, and a layered personal history.

Slow Poison: Idi Amin, Yoweri Museveni, and the Making of the Ugandan State

Mahmood Mamdani

Wits University Press, 2025

What lessons can we draw for intellectuals and academics on the margins of the corridors of power? What does it mean to be in conversation with those who are or will be in power and, at the same time, keep a ‘safe distance’ from power? Can we engage with power without being corrupted by it? How can we learn to live with ‘dirty hands’? There is no single answer, argues Mahmood Mamdani at the end of Slow Poison: Idi Amin, Yoweri Museveni and the Making of the Ugandan State. He insists that there is no manual for this terrain—only ‘the realm of practice’.

Slow Poison is a rich and textured account of Ugandan politics, and of postcolonial African politics more broadly. It is also, unmistakably, a personal history—one that reveals how Mamdani’s intellectual formation was shaped by his status as a minority, exile, anticolonial struggle and a sustained critique of power. The book appeared only weeks before his son, Zohran Mamdani, won the election for mayor of New York City, an outcome that invites readers to reconsider Slow Poison not simply as a work of political history, but as a meditation on political formation across generations. Read also against this background, the book’s relevance lies in what it suggests about how Zohran was raised: in a household where politics was not abstract or technocratic, but moral, historical and inseparable from lived experience.

Mamdani (from here on, ‘Mamdani’ refers to the elder) weaves together stories of growing up in Kampala as an Indian (‘Bayindi’); the paths taken by liberation struggles after 1960; the challenges of building a state in a newly independent African country (and the different paths taken by two of Uganda’s heads of state: Idi Amin and Yoweri Museveni); and how identities become political. He pays particular attention to the experiences of Africans of Asian (Indian) descent and Uganda’s other (Black) minorities. He also examines the market-driven reshaping of education, the rise of authoritarian rule, and asks what kind of political system—this may surprise some readers—might work best in deeply divided societies.

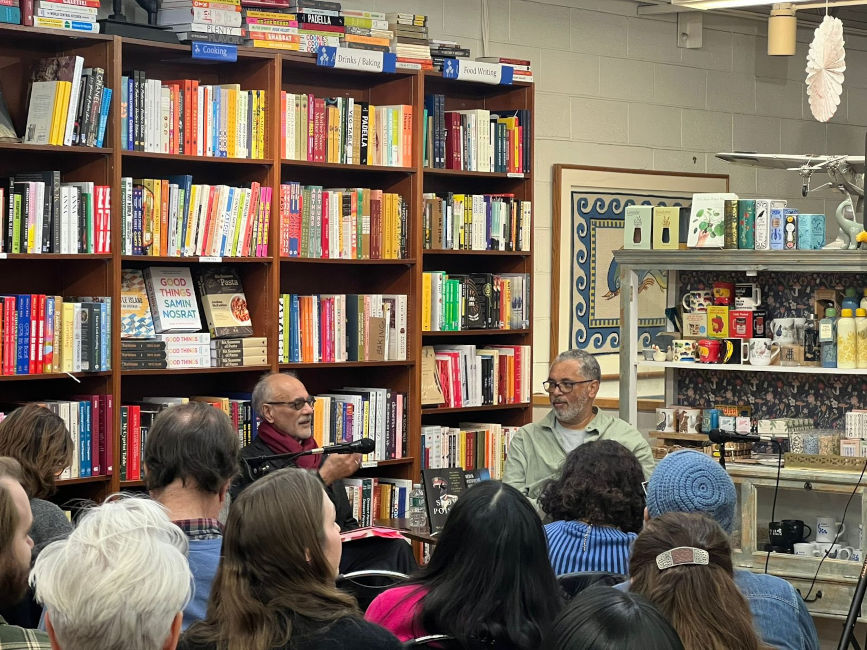

Unlike in much of his earlier work, Mamdani places himself inside the narrative in Slow Poison, which is why he refers to the ‘realm of practice’. At public events—including my interview with him for an event at a bookshop in New York City, where incidentally the mayor-elect turned up—Mamdani has admitted that early drafts of the book read like his previous scholarship, observing others from a distance, like Hegel’s Owl of Minerva. But he soon realised he had to enter the story as a character. In doing so, he also began to question academic ideas of objectivity and neutrality. And coming to terms with his own role in history; that he had lived these events, taken part in them, experienced the Asian expulsion personally, and was closely involved in efforts to liberate Uganda from Amin’s rule. He was close to Museveni: they were friends (their friendship dates back to 1972 in Dar es Salaam, where they were both exiles) and comrades. After 1986, Museveni had invited him to take on positions in government. Over time, however, Mamdani grew tired of Museveni’s fixation on staying in power.

Identity and belonging are among the book’s central themes. Mamdani’s own layered identity—Tanzanian parents, siblings born in different countries (Tanzania and Uganda), his own birth in India while his father was studying—becomes a lens through which to examine Asian African (Mamdani’s term) or Bayindi histories in East Africa, as well as broader questions of nationhood. These complexities followed him when he received a scholarship to study in the United States, through a programme similar to the one that took Barack Obama’s father to Hawaii. Even this opportunity became entangled in Ugandan identity politics: he later learned that a Black Ugandan member of the selection committee believed the scholarship had been ‘wasted’ on an Asian. The experience sharpened both his sense of racialised belonging and his commitment to efforts to break through it.

He points to Asian Africans who moved beyond narrow identity politics, including Sugra Vigram, an Asian woman who became a member of the Buganda parliament, and Rajat Neogy, ‘a different kind of muyindi, one with a literary sensibility’, who founded Transition magazine. The publication declared its independence from government or elite interference and, beyond Uganda, helped foster a freewheeling pan-Africanism. Neogy was eventually imprisoned and the magazine declined, but his legacy endures. (He was an inspiration for Africa Is a Country, the site I founded and edited until 2023.)

Mamdani credits his years in the United States for his political awakening. His time there was marked by his participation in the civil rights movement and a series of other formative encounters: his time with his white host family in Pittsburgh; an incident on a Nevada bus; run-ins with the Ugandan ambassador—who admonished him for ‘interfering in the internal affairs of a foreign country’—and the FBI. Mamdani recounts that after returning from organising with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in Alabama, the FBI knocked on his dorm-room door. They said they wanted to talk about a 1965 civil rights march in Montgomery that he had joined and asked whether he knew Karl Marx. Mamdani replied that he hadn’t met him. ‘No’, the agents said, ‘he died long ago.’ Feigning surprise, Mamdani asked why, then, they were asking him. The agents explained that Marx believed the wealth of the rich should be taxed and redistributed to the poor. Mamdani said that sounded like a fine idea. Concluding he was of no interest, the agents left—having inadvertently introduced Mamdani to Marx.

These incidents are striking given that it was a more oppressive time. Mamdani’s experience of relative tolerance evokes a sense of the possibility of a different experience for American Muslims. They also formed threads that would later run through his scholarship on race, power and postcolonial politics.

Upon returning to Uganda, Mamdani found himself, almost immediately, thrust into the crucible of national belonging, following Amin’s violent coup and the subsequent expulsion of Asians from Uganda in 1972. In Slow Poison, before addressing Amin’s role, Mamdani carefully reconstructs the social history of Asians in Uganda. He contextualises the crisis within the framework of British colonial rule, arguing that the implementation of colonial racial policies (in their application of apartheid between Indians and black people) laid the structural groundwork for later violence. The postcolonial state, rather than dismantling these hierarchies, continued to marginalise Indians.

Mamdani also complicates the dominant portrayal of Asians in this period. He argues that segments of the community refused to acknowledge their location within Uganda’s political and social hierarchy. Some reviewers have objected to this claim. Yet, as Mamdani demonstrates, refusing to examine the internal dynamics of the Asian community risks obscuring the conditions that allowed Amin’s explicitly racist expulsion order to gain popular resonance.

Amin himself appears in the book not as a caricature, but as a figure shaped by colonial military service: a former child soldier to the British who excelled in counterinsurgency and ultimately overthrew Milton Obote, Uganda’s first post-independence head of state. Mamdani challenges widely circulated depictions of Amin as irrational or monstrous, including the lurid cannibalism myths. He argues that such portrayals obscure Amin’s political intelligence and the colonial lineage of his methods. Reducing him to caricature, Mamdani suggests, prevents an understanding of the deeper forces shaping Ugandan politics at the time.

Israel also emerges as a key actor in Amin’s rise. He made his first overseas trip as head of state to that country, and it was a central player, along with the UK, behind his overthrow of Obote, before the relationship collapsed.

Mamdani interprets Amin as a Black nationalist seeking to build a Black Ugandan nation, with the expulsion forming part of that project, even as this ambition ran up against corruption and militarisation.

Julius Nyerere is another central figure, and here Mamdani offers a surprising interpretation: that Uganda shaped Nyerere’s legacy as much as Nyerere shaped Uganda’s. In both cases, very negatively. He suggests that Nyerere became deeply invested, even fixated, on removing Amin, a stance that reverberated across regional politics and contributed to Tanzania’s internal economic crisis. Mamdani is particularly disappointed that Nyerere never owned up to this.

The book is filled with memorable anecdotes, from his return to Uganda in 1979 and unexpected conversations with people like Joseph Kabila, to accidentally becoming an office bearer of the Ugandan North Korean Society and being sent to North Korea. These moments underline the surreal intensity of the period and of Mamdani’s own life trajectory. His time in exile—especially in the UK, where new refugees gathered at Gatwick hoping to glimpse familiar faces—produces moments of deep emotional weight.

One of the book’s major arguments involves contrasting Amin and Museveni. Mamdani portrays Amin as a nation-builder, whereas Museveni—despite their shared history—is shown to reproduce colonial divisions by mobilising ideas of ‘natives’ and ‘immigrants’ to maintain power. This, for Mamdani, is the ‘slow poison’ shaping the modern Ugandan state.

Mamdani’s sharp reflections on neoliberalism emerge partly through his experiences at Makerere University—he took leave from Columbia University in New York to work there for twelve years—and the possibilities he glimpsed for genuinely decolonising scholarship at the Makerere Institute for Social Research. I’ve had occasion to work with Makarere students in a Social Science Research Council-funded workshop for African PhD students. Their preparation rivals that of any top graduate programme in the world and they’re the best in Africa.

Those institutional contexts helped shape Mamdani’s broader critique of neoliberal knowledge production and his vision for a more grounded political and intellectual practice. Interestingly, he does not talk about another decolonisation project he undertook: to deracialise and decentre education at a formerly white South African university, although I assume his excellent TB Davie Lecture at the University of Cape Town, delivered in 2017, was his take on the limits to that work.

Mamdani’s argument in Slow Poison resonates with contemporary political experiments, including those that acknowledge cultural difference while insisting on a multiclass politics focused on equal political and economic rights. His provocative, personal book closes with an argument for federalism—not only for Uganda but potentially for much of Africa—as a way to ground national belonging in shared residence and citizenship, rather than inherited cultural identity.

- Sean Jacobs is a professor and director of the graduate programme in international affairs at The New School in New York City, and founder of Africa Is a Country and Eleven Named People.