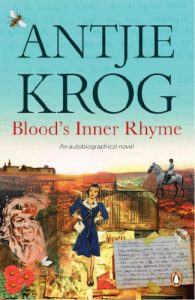

Wamuwi Mbao reviews Blood’s Inner Rhyme by Antjie Krog, a book preoccupied with a lifelong, struggling conversation between a mother possessed by the fever of Afrikanerdom, and a daughter who spent her life abhorring it.

Blood’s Inner Rhyme

Antjie Krog

Penguin Random House SA, 2025

Whenever a fellow literary proselytiser has pulled down a quaint and curious volume of Afrikaans lore, seeking to impress upon me some experiential fineness of literary spirit or the beauty of some transportive passage by someone whose first name is three initials, I can’t help but feel a sense of distance from it. Beneath the hum of every Nationalist lyric drums tyranny’s jackboot. Behind every nature-lover, a fascist lurks.

In the literature too, the faint or overt reverence for times past is not something I have much truck with. Many contemporary white Afrikaans artists are rather too enthralled by the misty mythology that characterises their tribe’s self-creation narrative: a large part of that mythology vocabularied by twentieth-century Afrikaner nationalism and the language of which it claimed ownership. The writing appropriates with Procrustean zeal a language whose cultural enmeshing should be a national celebration. It leaves us, instead, with a language tainted with narrow blood-and-soil chauvinism.

Contrast, then, Antjie Krog, whose beautiful, certain work of feeling has characterised her as perhaps one of the few white Afrikaans writers to step outside the stultifyingly chummy confines of that literary community. Over the long sweep of her writing life, she has consistently given herself over to thinking with both deep intellection and radical feeling about racial reconciliation and the importance of being (and saying) sorry. From the nineteen-eighties onwards, her poetry, her radio and print journalism, and her prose have plunged to the quick of white Afrikaner self-identity, picking at its certainties restlessly and with a passionate drive to disturb all comfort, including her own.

Krog’s latest work, the exceptional autobiographical novel Blood’s Inner Rhyme, narrates with arresting intimacy the untangling of a mother-daughter relationship in the current of the parent’s cruel decline towards death. Krog’s indomitable mother, who wrote as Dot Serfontein, died a decade ago at the age of 91, and so Blood’s Inner Rhyme reads like a novel-length mourning kaddish à la Allen Ginsberg. The book takes us through the last years of the matriarch’s life, framed through lingering visits, phone calls and other moments that provide a window into the long, vexed relationship Krog had with her mother. It’s a vision of a grasping intimacy driven through with each woman’s desire to know and understand the other, and so also driven through with each woman’s bafflement and hurt at the isolating otherness of their relation.

Serfontein belonged to that now-mothballed generation of writers who took it as their national duty to help symbolise the fantasial Afrikanerdom into existence. Serfontein’s writing, much of it serialized in women’s magazines, generated an idiom—of sentimentalised rural or railways-bound ordinariness, of Boer war martyrology and of endless self-commemorating—that has become ingrained in white Afrikaner cultural memory. At any rugby match where the stadium is filled with white people, you can still hear the strains of that communitarian pride in the fascist upswell of voices that greet those Langenhoven lines during the performance of our national anthem. Obedience takes a long time to die out.

The kind of writing that is a literary manifestation of this energy was undeniably successful in its time, and consequently has dated beyond relevance now, dispiritingly sententious in argot and alienating in its shofar-call embrace of an excluding world. It was a service literature for forging consensus, patiently committed to comprehending and illustrating the lives of ordinary Afrikaners. What to do with that knowingness, now? In Blood’s Inner Rhyme, Krog gives her mother a voice with which to defend herself, and that defence makes for intriguing reading. Describing the Voortrekker centenary, we glimpse through her eyes the collective fervour that bodied the Afrikaner nation into being:

The showgrounds were ghostly-lit by large bonfires and the trembling torches with which we stood guard at the Voortrekker wagons. Several children suffered burn-wounds which became a mark of honour. Something took hold of one: the barbaric roar of flames from giant fires; the smell of burnt rags and paraffin; the clenched fists of speakers; the out-of-tune piano accompanying choirs with possessed faces belting nationalistic songs; the preachers praying until sweat beaded their forehead. It awoke a fire, a fever, a mania in one … for us, it was the hour of rapture.

An inner preoccupation that threads through the book is the lifelong struggling conversation between the mother possessed by this fever, and the daughter who has spent her life believing it to be abhorrent. Krog’s adherence to her own political line, a rampant streak of individualism that has consistently placed her work outside the chummy binnekring of the white South African literary circles, is anathema to the credo of Afrikanerdom championed by her mother.

Blood’s Inner Rhyme is a story with a slightly different gait to earlier works such as A Change of Tongue. Nevertheless, it reprises Krog’s preferred devices—anecdote, interview, history, poetry—to tell an intriguingly other-centred memoir. Thatched from terse nursing-care notes (‘Pt. complained of itch on right side. There was a rash.’), epistolary exchanges and frankly intimate first-person narration, the story whirls around Krog’s restless speculation that the Afrikaner’s psychic stuntedness is a form of trauma. When her mother questions why Krog is interested in raking over the occluded details of what went on during the South African war—specifically, what violence women endured and why it was covered over—a rift begins to open between them:

‘But it is in my books!’

‘No, it’s not. I specifically looked. Nothing about trauma . . . it’s all about the building up, the taking hold, the getting a grip, the drive in education . . .’

‘. . . But why do you worry about this?’

‘Because I hope that, if we acknowledge that post-traumatic stress burst forth from us in terrible ways after the war, we might be more sympathetic about all the traumatic stress that has broken out in this country after 1994.’

To read this book is to become aware of the unutterable differences that open like potholes in the closeness any of us feel with our parents.

Some of it—the scatological detail—will be familiar from A Change of Tongue, but it appears here limned in a new light by the doubled ageing of the two women. Growing older, we know, is unflattering, and perhaps in the daughter’s close observation of the mother we glimpse a fear of what the gathering slide towards life’s exit might bring.

Here by us, three flats are empty. Old people whose children are overseas get invited to stay there, old people whose children have run out of money also. Looks like we are the last generation that has money, and everyone is concocting plans to pan it out of us. Every time I attend the monthly Eastern Light club, one or two life-pals are missing: children came to fetch them to one or other unknown destination, or one sees them in the back of small cars, sunken between grandchildren with two dogged adults in front.

We see in moments like this the mother’s articulate despair at the desolation and the captivity of that point: watching as one’s fellows are picked off by children who do not really care, or don’t care enough. The mother’s talent for language and her eye for detail, both waning as her life-force dallies in its last season, are faithfully conferred.

In many senses, this novel belongs to an older and more supple kind of writing, before autofiction hardened into a bulleted straitjacket. It draws obvious comparisons with Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking, but I think a closer comparison might be to Vigdis Hjorth’s ‘reality fiction’, or perhaps it is like a more jocular Tristes Tropiques. It’s a kind of storytelling that, presented here, is marvellously polyvocal, and it provides fitting evidence, if any was needed, of Krog’s narrative power.

In Krog’s book, we encounter her mother as the sort of irascible old white person many of us are familiar with, the kind to whom one feels a mix of exasperation and pity. As she is presented to us, she constantly defeats any sympathetic identification, although this makes her a far more difficult, more true-to-life character. At an early point in the novel, we glimpse her view of herself as ‘an old apartheid dinosaur’; initially sceptical of being cared for by a black nurse, she has her own small journey of contrition. Speaking about her new carer to her daughter, she betrays some capacity for surprise:

She was in Afrikaans High, the first group of black kids who went to a Model C school. And she speaks like you and me! We watch TV together. She knows I wrote books . . . it really is a big, big blessing that has befallen me. Some of the other old people tell me that the white nurses refuse to do any housework along with the care, and, between you and me, some pilfer things…

She seems almost bemused to have lived past the zenith and nadir of the volk and found herself on oblivion’s lonely shore. Her startling fervency contrasts with the nursing notes which tell of interminably sleepless nights, the squalid reduction to bowel movements and bathing. Nevertheless, the fictionalised Serfontein is very much of the Old Order, and she sits within the novel as an angry reminder that no matter how ardently democracy’s pitchforks may have driven apartheid from the scene, the old resentments are always ready to come roaring back again. At one point, reminiscing about watching from the farm as a bomber carrying Hendrik Verwoerd’s body flies overhead, she reflects:

I returned to myself and undertook then never to break down two stones lain atop of one another by an Afrikaans writer in the Afrikaans language, no matter how ill they fit. And I prayed that my hands would fall off before writing something trying to earn fame for myself at the cost of my people or of that which had been congregated for them in the years of tears and blood; that I would always remember that to write in Afrikaans was not a right, but a privilege that was bought dearly and paid for, placing a very heavy responsibility on me.

We hear in these words a stinging rebuke of Krog’s work, its perceived betrayal of volkisch proprieties. For all that Krog and her mother were fellow travellers in writerly self-creation, their different political inclinations—the mother conservative, the daughter radical—install a fraught distance that persists with acidic rancour over their intertwined lives together. It is clear that the feeling of wartime humiliation that lingered still in the budding Afrikaner conscious, and the sullying nearness of poverty in the post-war decades (‘the poverty was because of the war, but there was a degeneration among poor whites that was difficult to digest’) instilled in Serfontein a profoundly irrational adherence to the wrongheaded political cause of Afrikaner nationalism. When a young Krog and other writers from the Afrikaans Writers Guild light out for Zambia in 1989 to meet with the banned ANC, Serfontein resigns from the guild in a purple pique:

As the Guild will probably now be richly funded by the ANC, it no longer needs the support of writers who don’t want to be prescribed how to write in Afrikaans by blokes from the bushes . . .

And when, later that year, Krog and her family receive death threats from right-wing conservatives (plus ça change …), her mother coldly regards it as just desserts for Krog having sloughed her identity:

My mother is busy plaiting my daughter’s hair when I enter. She doesn’t look around. When near her, she says under her breath: ‘This house cannot become a refuge when you turn against your own people …’

Mother and daughter swing bloodily between love and anger over their imbricated years together. And yet for all that the older woman adamantly rejects her daughter’s political rebellion, and for all the incuriosity she displays about Krog’s later desire to root through the swarf of their cultural past, her robust pragmatism does allow her to reflect, at least to some extent, on whether there was anything at all to be salvaged from the wreckage of the nationalist dream:

I have now bought two volumes of poetry by the Pretorius fellow from the Boeremag. Heavens, they have already been in jail for more than ten years without trial. He is now busy with his doctorate in theology, but ag, what does it help to give your life for what was supposed to have been the Afrikaner cause? Would I have done it?

It is difficult to view with readerly sympathy the mother’s regret for the passing of a misguided tyranny, particularly when the vacuous collective social crisis occasioned by the end of the old regime has given rise to a cracker barrel belligerence that keeps company with the current trend of right-wing ugliness which picks up wherever white people are asked to share the country they live in, rather than profiting disproportionately from it. But in this novel, we glimpse what that tribal fealty wreaks on the airless confines of a close family. We are reminded that Krog has always been prepared to engage the risk of being deeply and publicly personal: this novel has a difficult sentimentality about it, which is ultimately its great strength.

And what of Krog herself? In this quasi-fictional rendering, she is a somewhat muted presence, part subject and part biographer, in the text. When she does intrude, it is with a rueful awareness of the times she faltered before her mother, kept quiet to preserve peace, shrank back from conflict. With stark simplicity, she flags that there was always more she might have said: ‘and because she was my mother, I didn’t ask …’ is a ringing refrain at one point. She does not spare herself from truth’s cruelties (there’s a hilarious, appalling account of an overseas trip riven with bodily calamities), and her fireside exchanges with her siblings provide some of the best moments in the novel.

This is an interesting book to read from the perspective of 2025. Recent events in the long post-apartheid moment have shown many white Afrikaners to be a collective of thin-skinned special pleaders. Having sullied themselves in their braying obeisance to an asinine regime of white supremacy, they have passed uncowed into the twenty-first century as a band of maladapts and malcontents, hardly deigning to feel shame for their part in the great crime committed on their behalf. Whatever democracy promised to take away, pecuniary privilege has largely preserved and shored up. As an inevitable knock-on effect, the Afrikaans culture industry is in boastfully rude health: its mongers and wallahs can boast of a teeming industry of films, plays, music and literature in which the solipsism of white Afrikanerdom is indulged. The corporations and media houses and cultural organisations that prop up this self-contained industry by giving out rashly generous rewards are not disinterested parties: they sustain the bullish protectionism that conspires to hold back the perpetual mutation and change that is natural to any language.

Read against this present, Blood’s Inner Rhyme does not play to the gallery: it is not ‘magisterial’, not the sort of thumper that one might expect from someone like Krog writing about someone like her mother. Conversely, the book’s relative briefness feels deft, adroit in its handling of the difficult matter of what lies unfinished when someone close to us dies. I hope that, despite what Krog says, this is not her last book, but if so, it is a superb, cleansing ending.

~~~

- Editorial Advisory Panel member Wamuwi Mbao is an essayist, cultural critic and academic at Stellenbosch University.