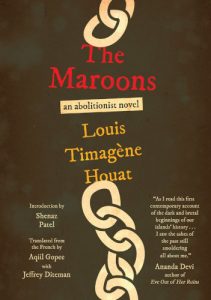

The JRB presents an excerpt from the rediscovered classic The Maroons, first published in 1844 and released for the first time in English this year by Restless Books; the only known novel by Black abolitionist and political exile Louis Timagène Houat.

The Maroons

Louis Timagène Houat (Translated from the French by Aqiil Gopee with Jeffrey Diteman)

Restless Books, 2024

The Cave—Marie and Frême

Our poor Maroon was alive. The sky had spared his life, turning his fall into his very salvation.

From the spot where he had fallen, the mountain looked terrifying: at an elevation of more than two thousand meters, it formed a sheer overhanging precipice, holding nothing from head to foot but sparse, detached, inaccessible crags. The maroon hunters gathered that the Câpre, their human prey, was as good as dead down below! However, as he was falling, he had, in an instinctive, abrupt movement, thrust his hands against the mountainside. Through a twist of fate, he had been able to grasp onto one of those long, thick creepers that sometimes dangle like ropes along the side of a ship. He let himself slide down, gently, until he reached a sort of plateau nestled amidst the rugged terrain.

He could not believe it; he was saved! All the same, the merciless squad of hunters could still rain deadly rocks down upon him. He immediately looked for somewhere to hide and noticed a sizable opening right at the heart of the mountain, marking the beginning of the plateau. He thrust his head inside. It was a large cave. He entered, unable to see anything at first. But as his eyes grew accustomed to the darkness, he suddenly stopped. What was he seeing? In a corner, sat a young White lady cradling a mulatto child at her breast!

Startled by this sudden apparition, he stood frozen in place, his eyes wide with disbelief as he peered into the darkness. The dread of Whites and of ghosts loomed in his mind. He was petrified, and dared neither move forward nor retrace his steps. Meanwhile, the young lady, preoccupied with nursing her child, did not raise her head upon hearing his approach. In a gentle voice, she inquired:

‘Is that you, Frême?’

Overwhelmed with agitation, the Câpre stammered out a jumble of unintelligible syllables, incapable of articulating a coherent response.

‘Oh, my friend!’ she continued, ‘you took your time today … I heard dogs barking … I thought about the squadrons, and I grew anxious for us …’

Those last words snapped the Câpre out of his confusion. Understanding that he was neither trapped in a dream nor in the clutches of hunters, he regained his composure and spoke in the calmest tone he could muster:

‘Indeed … There are dogs and hunters around … but the good Lord … He is here too …’ Nervously, he added: ‘I am not Frême, ma’am …’

The young lady shuddered at his confession and raised her head. Her eyes were so full of astonishment that the Câpre tried to reassure her at once:

‘Do not fear, ma’am, I am nothing but a wretched maroon, pursued by the barking dogs you heard. I lost my footing and ended up here … I have no intention of causing harm to anyone. I am only seeking shelter …’

A wave of relief washed over the young lady. She wiped her forehead and sheepishly said:

‘Oh! You gave me a fright!’

At the same time, a young, tall Negro strode into the cave. His features were aggressive, his limbs knotted, his body lean and supple.

‘What happened? Who frightened you, Marie?’ he asked, rushing to the side of the White girl without noticing the Câpre standing nearby.

‘No, it was a misunderstanding, my friend …’ she continued, visibly relieved at his arrival. Pointing to the Câpre, she said, ‘It is just a poor maroon seeking refuge with us.’

The Câpre stammered a few words of apology.

‘Oh!’ exclaimed the tall Black. He looked at the other in astonishment. ‘But how in the world did you end up here, brother?’

‘Ah, well!’ began the Câpre, letting his guard down. ‘When injustices become unbearable, we’ve got to abandon ship, you know? The master is a brute. I left his estate and set out for the Salazes, following the path of the maroons. But up on the mountain, I got hungry. Walking around, I spotted a bunch of guavas, but no sooner had I eaten two than the squadrons appeared and let their hounds loose on me … I turned to run away—but I couldn’t see where I was going. I took a step back and next thing I knew, I was falling—I had been venturing too close to the edge of the cliff without even realizing it … Fortunately, I was able to grab onto a vine which led me here.’

‘Talk about luck!’ exclaimed Frême, shaking his head in amazement. ‘We’ve been in this cave for over twelve moons, and you’re the first, brother, to find your way here. There’s no path, neither from above nor below. The only way to get here is by a stroke of chance! But, my friend, you must be tired and famished! Take a seat here on this bench, and let’s share a meal together …’

He opened his bretelle—a kind of knapsack—and took out a few fruits that he had just picked. Marie, who had laid her now sleeping child onto a mat spread out next to her, went and fetched some grilled bananas, sweet potatoes and a cabbage salad that she had prepared … Soon, sitting in a circle in the manner of the Arabs, the two Blacks and the White woman began their modest meal, pursuing their conversation.

‘So the masters are still as wicked as ever …’ observed the young lady, speaking to the Câpre. She seemed sympathetic.

‘Always, ma’am … If it isn’t them, it’s those who represent them, and it boils down to the same thing for the poor slaves … we suffer the brunt of all this misery and torment. We endure malnourishment and back-breaking labor, yes, but it gets worse … you must have heard of the masters, my own included, who scar our bodies with canes, sometimes even cutlasses … They shackle us with heavy chains, and we waste away in the stocks or in prison … They show no mercy, shattering our bones, our limbs, even searing our faces with firebrands. They trample us with their shoes, form gangs to spit on us and force the filthiest things into our mouths … They yank out our hair, pull out our teeth, and even pour boiling water down our throats …’

‘Stop! Stop! Please!’ cried the White girl. Her face had paled in horror.

‘I understand, ma’am,’ continued the Câpre, ‘I understand that this shocks and pains you because you are kind. But why aren’t all Whites like you? They believe that we can’t feel pain, and if we dare complain to their judges, they turn a blind eye, deaf to our pleas, and label us liars, dismissing us as unworthy subjects. Oh! It’s very sad, ma’am … and I don’t know when the good Lord will put an end to this cursed profession, the Black slave. Even hell is not worthy of such an occupation … However, I’ve heard that many Whites in Europe care about our plight, advocating for our freedom, and that this freedom, which they call emancipation, will be coming soon …’

‘Oh joy!’ piped Marie. ‘All those injustices will finally stop!’

‘If you ask me,’ said Frême, shaking his head, ‘I don’t believe any of this will happen. I’ve been hearing these rumors for a while now, and they always talk about emancipation coming soon, but it still hasn’t. The Whites will be Whites. They only look out for themselves. The Blacks are their property, their slaves. They’re in no hurry to set them free. Some may pity the Blacks and what is done to them, but many others think and claim that it’s a good thing; that we are happy as we are and good for nothing but being caged, shackled for life. They support each other, the Whites; they are strong, they are rich. They use the same money they gain from slavery to promote and maintain it. And beyond money, they still promote the ideas of color, race, domination, ships. Everything they get from our labor is proof that slavery works: sugar, coffee, cocoa, cotton, pepper, cloves, nutmeg. Go figure! Besides, how far away is Europe? A deep, wide sea separates us from them, and they have all kinds of things besides us to think about. They don’t see us, don’t know us; they might be thinking all kinds of things about us. I think they’ll take care of those close to them and will forget us because we are far away. They’ll take care of the woods and the animals. Not us. They’ll make laws, like they do here, for the preservation of plants, fisheries, horses, dogs, and birds; but not for our preservation, nothing to improve our lot. Nobody will care about our freedom …’

‘Oh!’ exclaimed the gentle Marie, ‘why would you say that, Frême? God is great. He is mighty, and you know how good He has been to us. He saved us. He will also save the Blacks. Keep faith! The Whites have hearts, they have minds, intelligence. The spirit of justice and practical interest will surely enlighten them, and they’ll come to realize that slavery is a wretched thing, and it must be abolished; they’ll understand that this is the best path forward for everyone.’

‘Yes, yes! Ma’am is right,’ said the Câpre firmly. ‘Those are fitting words, and I wholeheartedly agree. I put my faith in this cause, for it is just, and it must come to pass. In the meantime, I have fled the master’s house; I shall bide my time as a maroon. But let’s change the subject, let’s talk about you, brother … Truly, I can’t believe it! How did you end up here with such a lovely White lady?’

‘Oh! My lady!’ said Frême. ‘It’s a long story. If you won’t find it boring to hear—’

‘No, not at all,’ the Câpre eagerly assured him, his curiosity getting the better of him.

‘Well then!’ continued Frême, ‘I will try. But I will need Marie’s help …’

‘I’ll help,’ said Marie timidly.

And so, the story began. The Câpre listened attentively to Marie and Frême’s tale, of which we shall endeavor to give an abridged account, though we cannot fully capture all its intricacies or its innocence.

~~~

- Louis Timagène Houat was a French writer and physician. Originally from Bourbon Island, now known as La Réunion, he was the author of the first novel in Réunionese literature, Les Marrons, which he published in Paris in 1844.

~~~

Publisher information

The first English translation of a rediscovered classic, and the only known novel by Black abolitionist and political exile Louis Timagène Houat, The Maroons is a fervid account of slavery and escape on nineteenth-century Réunion Island.

Frême is a young African man forced into slavery on Réunion, an island east of Madagascar in the Indian Ocean. Plagued by memories of his childhood sweetheart, a white woman named Marie, Frême seeks her out—but when they are persecuted for their love, the two flee into the forest. There they meet other ‘maroons’: formerly enslaved people and courageous rebels who have chosen freedom at the risk of their lives.

Now available in English for the first time, The Maroons highlights slavery’s abject conditions under the French empire, and attests to the widespread phenomenon of enslaved people escaping captivity to forge a new life beyond the reach of so-called ‘civilisation’. Banned by colonial authorities at the time of its publication in 1844, the book fell into obscurity for over a century before its rediscovery in the nineteen-seventies. Since its first reissue, the novel has been recognised for its extraordinary historical significance and literary quality.

Presented here in a sensitive translation by Aqiil Gopee with Jeffrey Diteman, and with a keen introduction by journalist and author Shenaz Patel, The Maroons is a vital resource for rethinking the nineteenth-century canon, and a fascinating read on the struggle for freedom and social justice.