Daughter in Exile by Bisi Adjapon is a pacy, character-driven novel that surveys the many burdens of living as an irregular migrant, writes Shayera Dark.

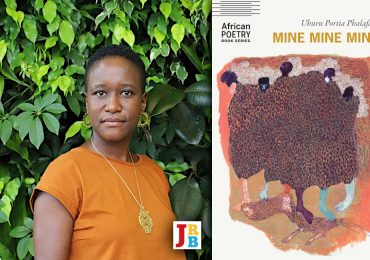

Daughter in Exile

Bisi Adjapon

HarperVia, 2023

Bisi Adjapon’s novel Daughter in Exile is a tableau of misfortunes, spanning two continents over a twelve-year period beginning in 1995. With its super-fast-paced and dialogue-heavy narrative, Daughter in Exile reads like a first novel, and was in fact written before The Teller of Secrets, Adjapon’s official debut (originally published as Of Women and Frogs by Farafina Books in 2018, before being acquired and published by HarperCollins under its new title in 2021).

Daughter in Exile opens in Senegal’s capital Dakar, where Lola, a Ghanaian–Nigerian translator at the Thai embassy, meets and falls in love with Armand, a Haitian–American marine stationed at the American embassy. He dreams of becoming wealthy, and together they hatch a plan to buy gold illegally mined from Ghana to sell in Europe for a profit. However, shortly afterwards he’s deployed to Barbados, leaving Lola to initiate the scheme with the two-thousand dollars he’s wired to her.

In his absence, Lola travels to Ghana, where she’s conned out of her fiancé’s money. She also finds out she’s pregnant, news that unravels her relationship with her mother, who has already refused to entertain the idea of a non-Ghanaian son-in-law. As her pregnancy progresses, and with Armand’s assurances that his close friend will take care of her until his return, she quits her job and leaves Senegal for America, ready to give birth and start a new life as a writer:

I was leaving behind friends, a job, my mother, my sister, and the security of a culture to which I had always belonged. Going to have a baby in a foreign land in the middle of the worst snowstorm of the year, with a fiancé in the Caribbean, to stay with a best friend I had never met. The plane took off.

It was too late to change my mind.

Unbeknownst to Lola, that flight marks the beginning of her ten-year ordeal, first as a legal visitor with unstable living arrangements, and then as an ‘illegal’ migrant desperate for work. On arrival, she discovers Armand’s so-called friend knows nothing about his arrangement, and he slyly deposits her at a hospital. For his part, Armand, livid over the money she lost, abandons her. Alone, penniless, but determined to make her way in America, Lola leans on the American friends she made in Dakar, an aunt, and a series of church members to navigate her new home, one she finds increasingly distressing and at odds with the images she’d seen on cinema screens in Dakar, ‘a land flowing with dollars, where Michael Jackson and Diana Ross held street parties, and everyone could afford lobster’.

‘To emigrants, America was this magical place where all you needed was a willingness to work hard for your fortunes to change,’ she notes of the early years of her self-imposed exile. ‘No one told you America could crush your bones, grind you into dust. And yet, even as reduced as I felt now, I believed the American magic existed. It was just so bloody hard to find it.’

Without the requisite visa, despite her bachelor’s degree, Lola’s employment prospects are bleak. She tries working as a waitress but without a social security number the job falls through her hands like water. She manages to find another job as an au pair for a white American couple, but when their baby falls sick in her care, her once friendly employer terminates her position at short notice. One of the white American friends she made in Senegal explains that her connection to Africa and Armand may have contributed to her firing:

… people believe [Aids] started in Africa. And you told them Armand was Black. They were worried about drug use, you know? Heroine. Needles. The sort of thing that spreads Aids … For all they knew, you could have contracted Aids from Africa or even Armand, and passed it to their baby.

Lola eventually secures a job better aligned with her career at an embassy, but even then, her trouble doesn’t end. Beyond racism, American parochialism, and the burden of living as an irregular migrant, the second half of the book dedicates itself to elegantly exploring female sexuality, religious hypocrisy and the demonisation of single mothers. Lola’s fellow churchgoers are uncertain of how to treat her. ‘They couldn’t civilise me, so they didn’t know where to shelve me,’ she observes. In one jaw-dropping scene, the pastor, who alludes to her in his sermons about the dangers of premarital sex and jails ‘packed with boys raised in single-parent homes’, brands her a ‘widow-in-deed’ and calls on the married couples in the congregation to rise and ‘say how blessed you are that the Lord gave you your mate’. Later, some congregants she barely knows pressure her to give up her second child for adoption, claiming it will be for the best.

Still, despite the holier-than-thou judgement and ill-advised remarks, the church provides Lola with a sense of community, compassion and refuge in a world that constantly shuts its doors to her.

While there are echoes between Daughter in Exile and The Teller of Secrets—with both surveying similar feminist themes and centring on the travails and triumphs of a female protagonist—it is in The Teller of Secrets that Adjapon achieves her rhythm. With its balanced composition of dialogue, description and exposition, The Teller of Secrets allows readers to sit with a character, rather than flitting rapidly from one disastrous scene to another as Daughter in Exile has a tendency to do. For instance, Lola’s swift engagement to Armand, after a few half-serious discussions about the future, and Armand’s decision to hand her his mother’s ruby ring and wire her two thousand dollars—which he emphasises is a substantial sum for him—read as the stuff of fairy tales. What’s more, Lola’s excruciating naïveté sometimes teeters on the cliff-edge of stupidity and one wonders whether she’s a unsophisticated teenager or a twenty-something adult with a university degree.

Still, like its successor–predecessor, Daughter in Exile is no slacker when it comes to eye-catching metaphors. In one scene, following yet another harrowing experience, Lola compares her feelings of turmoil amid joy to the persistent itch of ‘the plastic tag on a new dress’. Elsewhere, grief is a train grinding through her:

I held on to its poles, trying to remain upright, not to fly out the window and spiral into a dark hole where the earth was moist and smelled of rotting flesh.

In the novel’s final scene, Lola’s reconciliation with her mother, she says wistfully: ‘I did my best.’ Her mother’s reply is ‘You did well, my daughter.’ But given the many dark nights and unrelenting mishaps that befall her in America, it feels as Lola continues to spiral into a bottomless hole for a long, long time, leaving one to question whether her self-exile is worth the pain.

- Shayera Dark is a writer whose work has appeared in publications that include LitHub, Harper’s Magazine, Al Jazeera, AFREADA, The Kalahari Review and CNN.