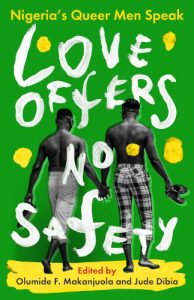

The JRB presents an excerpt from the forthcoming book Love Offers No Safety: Nigeria’s Queer Men Speak, to be published on 29 August 2023.

Love Offers No Safety: Nigeria’s Queer Men Speak

Edited by Olumide F Makanjuola and Jude Dibia

Cassava Republic Press, 2023

I Was Forced to Come Out

Mdue, age 29, Benue

I am the last of seven children and I have three sisters and three brothers. I grew up in a religious household. I was a quiet child—I was always in the background and did not mingle with other kids. I was not interested in things boys were interested in, like football. I was more comfortable playing with girls, and it was always more fun hanging out with my sisters. Growing up, my parents travelled a lot and they used to ask what treats they should bring back for us from their trips. My brothers would ask for toy cars and balls, and I would always ask for dolls. My mum would return with dolls for me; she was that sweet. I played with dolls until I was in secondary school when I was about thirteen years old. By then, my parents had become uncomfortable and stopped getting them for me. When that happened, I started buying the dolls myself with my pocket money and hiding the purchases from them. I would also sew dresses for my dolls. There was a time I made a dress for my doll, and it was so beautiful that my sister took it to a fashion designer to make the same style for her.

I was fascinated with hair. I loved watching Indian movies to see the length of the Indian actresses’ hair. At the end of each movie, I would wrap my T-shirt around my head to imitate their long hair and dance around with it. I felt comfortable doing this alone, as soon as I heard footsteps, I would take the T-shirt off my head and act like a normal boy. Also, I loved being part of the team who helped to remove my mother’s or sisters’ plaits and hair extensions. But as soon as my dad came back home, he would ask me to leave the women. My dad was less comfortable with me than my mom who was more accepting.

I did not come out, I feel like I was pushed out. In 2011, I had someone over for the night and while I was seeing them off the next morning, my cousin went to my room to get something, and she found used condoms on the floor. This was how the rumour that I was gay began to spread to my other cousins. My immediate elder sister, who was not around at that time, got wind of it and called to ask if I was gay. I told her I did not know what she was talking about. She persisted but I still feigned ignorance. In resignation, she said I would have to deal with my dad since I did not want to talk to her, and she hung up the phone. I felt sick instantly. At the time, I worked at a little shop, so the morning after I spoke with my sister, I told my boss I was not feeling well, and I left for my friend’s place. I stayed with him until it was late because I was scared to go home, afraid my sister had talked to my dad, afraid of facing him. My dad was a strict disciplinarian. Later that night when I was sure he would have gone to sleep, I went home, snuck in, and went to bed. The next morning, when I greeted my dad, he did not act like anything was wrong. He did not say anything to me about the incident. He was acting normal with me. Things remained normal for a while until my mother returned from one of her travels, and even then, she also did not say anything about the incident. I told my friends about it, and they suggested that my sister may have made an empty threat and did not tell them. But that same night I had this conversation with my friends, I was summoned by my parents. I was asked to sit down when I got to their room, and they started praying. Now, my parents never ask you to sit down if you come to their room, you are expected to stand no matter what, so I knew the moment I had been dreading had finally come.

While we were praying, my head was spinning, I was wondering what questions they were going to ask, and what answers I would give them. I was mentally preparing myself. After the prayers, they asked if I was familiar with the word homosexuality and I answered yes, and then they asked if I was gay, and I replied that I was not. Then my mother said, ‘We will not beat or kill you, you are our son, just talk to us.’ She told me that they had reflected on my life and wanted to know the truth, so they asked again and this time I said yes.

My dad burst into tears, and I was taken aback. My mum stayed composed. After my dad pulled himself together, he started asking uncomfortable sex related questions, trying to know what role I played in the situation—if I was the male or the female partner. But I told him I was not comfortable talking about it with them. After this, my dad made rules because he felt my friends introduced me to homosexual-ism. His rules prohibited me from having my friends over since he could not tell which of them was gay. I was also banned from wearing skinny jeans because he heard that only gay people wore them. I had recently pierced my ears, but I never wore earrings at home because of my dad’s strictness. He told me he never wanted to ever see me with earrings and threatened to cut off my ears. My curfew became 7 p.m., immediately after I close from work.

I have to say that my dad is a proud person. He did not want to associate himself with a gay son publicly so he delegated the task of taking me to the priest to cleanse me from homosexuality to my mother. My mum made the appointment, and we went to see the priest, who gave me a nine-day Novena. I took it seriously because I felt I had let my parents down. The way a Novena works in the Catholic Church, the person is supposed to have an intention, that is, a request to God. I asked God to take away my homosexuality if it was unnatural. I lived a low-key life during this period—I stopped hanging out with friends and respected my parents’ rules. I was twenty-four years at that time.

While this was going on, I was also battling with an extra year in school. I was supposed to graduate in 2010, and my parents blamed homosexuality for my failure. I was a bright kid in secondary school and usually came top of my class. I was the one my dad thought would graduate with a first-class or second-class upper university degree, so it was devastating for them when I told them I was not in my graduating class.

I remember having deep conversations with my mother about the incident. Besides her, only two of my siblings talked to me about the incident, the rest were silent and acted like they did not hear about it. My two brothers who talked to me told me to stop being gay because it was unnatural, a sin, and I was tarnishing the family name. But the conversations I had with my mother centred on her effort to understand what was happening to me. She asked me questions like how it started and how it happened. I tried to explain to her that it was not something that started randomly, but something that had been part of me since birth. We had honest conversations and I gave her instances of my childhood, but she said she felt my interest in female activities and clothes just meant that I was going to grow up to be a womaniser and not a gay man. I tried to let her understand that this was something natural and I did not pick it up from anywhere. She tried to bring up the religious angle—if this was natural then God would not have made man and woman. She asked how I was going to procreate. I told her if that were the case, all men would be fertile and there would be no barren women. I tried to make her understand that being heterosexual did not guarantee procreation.

This happened between 2015 and 2016. She asked me to keep our conversations a secret as my dad was very ill during that period and she did not want anything to have a negative impact on his health. No one has talked about my sexuality since then, and even though I still live in the family house, I try to keep my sexual life away from my family. I am the only child living with my parents now; they are reluctant to let me rent my own space. But I went ahead to rent an apartment where I stay occasionally and conduct my private life away from their gaze.

Growing up I had straight friends who all had girlfriends, so I had a girlfriend too. In fact, you were the man if you had more than one girlfriend, which my friends and I did. This happened between the ages of sixteen and twenty-two. Even though I was dating girls, I still secretly nursed the fantasy of being with a guy. I felt I was the only one with that type of urge in Nigeria, so I ignored it. The turnaround happened while I was in university. I met this guy who came on to me in a subtle way. When my roommate left town to spend the weekend at home, I invited him over to spend the night with me. It was a crazy night and I surprised myself. I was sexually aroused and here was my fantasy sitting right in front of me. It was my first experience with a guy and the only difference between being with him and a woman was the way he made me feel. He just knew what to do. He made me experience feelings I had never felt in my whole life and touched me in places I never imagined were sensitive. It was a total turnaround for me, we bonded, and he introduced me to the network.

I have been in relationships, but they have never gone beyond eight months. That is the mark. Once it is eight months, it is over, and I walk away. There is a lot of infidelity in our community and fidelity is important to me. I am not the jealous type; I do not search through my partner’s phones. I give trust and space, and expect the same. However, I have been unfaithful too. Sneaking around can be fun. I once fooled around with someone who already had a lover that lived in the same neighbourhood as I did. He would see his boyfriend and then come to see me too. He broke up with his partner and we started dating exclusively until he hooked up with a friend of mine. It shattered me. It was one of the two times I have cried in a relationship.

I have issues with the way roles are stereotyped in a relationship. I do not necessarily accept that masculine gay men should play the ‘male roles’, and effeminate gay men play ‘female roles’ in a relationship because that is the way it happens in a heterosexual relationship. It annoys me when people ask me, ‘Who is the man?’ or ‘Who is the woman?’ after I introduce my partner to them. I tell them to look at it as two men who are just in love.

~~~

- Olumide F Makanjuola is a Sexual Health and Rights advocate with specific interest in LGBT rights. Makanjuola’s work focuses on expanding public knowledge and discourse on queer issues through new and alternative narratives. Makanjuola is an alumnus of the International Visitor Leadership Programs, Associate fellows of the Royal Commonwealth Society, and honoree of Queen Elizabeth II.

- Jude Dibia is an author, queer rights advocate, winner of the Ken Saro-Wiwa Prose Prize, and shortlisted for the Nigeria Literature Prize, Common Wealth Prize and the Swedish Natur och Kulture Pris. His debut novel, Walking with Shadows, is the first full length novel devoted to queer issues in Nigeria. Dibia currently lives in Sweden where he works with displaced artists as the administrator of the Malmö City refuge artists’ programme. He is working on his next novel.

~~~

Publisher information

Nigeria, like many countries in Africa, grapples with deeply ingrained stigmas and pernicious laws targeted at LGBTQ+ individuals, fostering a harmful climate of fear and threat to their existence. Despite the repressive environment, Nigeria’s queer community remains defiant in telling their stories.

Love Offers No Safety: Nigeria’s Queer Men Speak, captures the stories of queer men across age, class, and religion from different parts of the country, in their own voices. Edited by Olumide F Makanjuola and Jude Dibia, these narratives encompass a range of experiences, revealing the complexities of navigating society, family dynamics, friendships, and romantic relationships as a queer man, while confronting the daily realities of societal prejudice.

This timely collection of personal stories is the attestation of hope and resilience, but also an important step towards educating society, dismantling harmful stereotypes and misconceptions surrounding queer Nigerian men.