Set in early twentieth-century Zimbabwe, Chinongwa follows the life of a young girl forced into child marriage with a much older man. Chinongwa is taken in as a second wife, and her relationship with Amaiguru—her husband’s first wife—is affable at first, but soon sours, as both realise that neither can flourish within a complex patriarchal system that orients them both as commodities. First published in 2008, a revised edition of Chinongwa was published in 2022 by Weaver Press and Modjaji Books. Fungai Machirori sat down with Lucy Mushita for this interview.

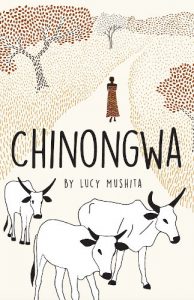

Chinongwa

Lucy Mushita

Modjaji Books, 2022

Fungai Machirori for The JRB: There is a lot of power to the opening lines of books. The opening line to Chinongwa reads, ‘Chinongwa Murehwa was nine, but her age was not vital. Just her virginity.’ I am interested to know how you came to that as an opening sentence for the novel.

Lucy Mushita: I started writing this book so long ago that I don’t remember exactly. I must have rewritten the opening line at least fifty times. I suppose I wrote and rewrote that line until it sounded right. It conveys that what the family wanted was a girl. And what they wanted was a virgin. And I think that line sums it up. She wasn’t marketable if she wasn’t a virgin. And she wasn’t marketable if she wasn’t a girl. And that’s all they needed. They didn’t really care who she was and her age wasn’t so important either.

It’s also based on a true story. My memory is that I’m between the ages of three and five. And a lot of the men were working in town. Remember that during apartheid, men worked away from their communities and were not allowed to have their wives with them. And the big guns in the villages were the elderly women, the Ambuyas. And for us kids, there were the good and the bad Ambuyas. And the good ones were the ones who gave you peanut butter, or a spoonful of jam or sugar, and put it in your mouth. The bad ones would smack you and tell on you to your mother. Even the nice grandmothers who we loved would smack you if they caught you being naughty. But there was this one who never did. By that age, I already understood that I could get away with murder with her. All of us kids didn’t respect her. I remember us kicking her hens and throwing her kittens in the air to see which one landed first. She would always weakly tell us to stop and not do that. I can still see the adults sitting in the shade, some laughing at what was happening. She would never smack us.

I realised when I was older that she had been given away when she was young. She may have been seven or eight years old. She may have been nine or ten years old, we don’t really know. But by eleven years old, she was a mother.

The JRB: Wow. Do you think that it was that experience that made her demeanour that particular way?

Lucy Mushita: I think so. Also, she was in a village where we didn’t really like her because she was younger than the other grandmothers. And she didn’t have a man. We didn’t like women who were not married. They were kind of an affront. I also think that other women feared she could take their husbands. She had a bad reputation. And everybody wanted to forget what had been done to her. But every time they saw her, they could not forget. So the only way they could deal with it was to make her a pariah.

So, as a child, I saw a very apologetic woman who kept to herself. I based some of Chinongwa on this, especially the characters of Amaiguru and her husband, Baba Chitsva, who would tell her that he had never wanted her. At first I was very angry with Baba Chitsva. But as you write and go into each person’s point of view, you suddenly see things completely differently.

The JRB: What is that experience like as a writer, to have that sort of engagement with your characters and cultivate empathy for them?

Lucy Mushita: It was a very strange exercise, writing the book. I finished the first draft after seven or eight years. At first I thought I knew the story and reckoned I’d write it in one year. When I write, it has to be visual. I need to see the person. I need to hear their voice. And so I would write and rewrite and write and rewrite and throw things away. I wrote it in the present, wrote it in the past; it was just written so many times. In the end, I wrote the second version in the first person, though I had initially written it in the third person, which just didn’t work. That way, I could go deeper into each character, because sometimes, even as they described the same events, they didn’t see them from the same perspective. So I thought the best thing was to write it from each character’s point of view. And every time I went into somebody’s character, I could see clearly from their point of view, and in the end, I could see why there were these misunderstandings. Because Amaiguru used to be a wonderful person. And then you look at things from her point of view and you think, well, she had quite a lot to dislike about her situation when Chinongwa was taken as her husband’s second wife. She had done something immense to say thank you to him, and yet he was ungrateful. So that’s how she saw it. She also saw herself as Chinongwa’s mother in a sense because it was her who made her a woman. For her, her husband and Chinongwa were not grateful.

The JRB: Amaiguru thinks that by incorporating Chinongwa into the home she is showing gratitude to Baba Chitsva, and ushering this young girl into womanhood, albeit a very flawed and accelerated womanhood. But that’s not how things go, and there follows a very clear scenario in which patriarchy wins and neither of these women end up happy. I’m quite interested to explore what you think about that as a theme in the book?

Lucy Mushita: Well, in the beginning, like I said, I hated Baba Chitsva. I knew before I started writing the book. He used to say, ‘You little woman you!’ even though he was having kids with her. He never respected her. And she thought she deserved respect. But I think everywhere in the world where you have a patriarchal model, it’s the man who has the power because he owns everything. And only a man can say to a woman, ‘I don’t want you here.’ Society has decided that an unmarried woman is not worthy of respect. So women strive to stay married so that they can keep being respected, and their respect only comes through the man, who may not even be interested in them. Baba Chitsva could very well have said, ‘I don’t want this child, Chinongwa, as a wife’. He was rich enough. But in the end, he slept with her, had children with her. But he never respected her. And eventually it is these two female characters, Amaiguru and Chinongwa, fighting each other for a man who—deep down—doesn’t love either woman. Both are victims of a system that says a woman is not respectable if she is not married, while men are deemed respectable regardless of what they do. The question doesn’t even arise.

The JRB: My next question centres around the theme of child marriage, which is very topical. What was your interest in setting this book in a historical setting—the early twentieth-century—rather than contemporary Zimbabwean society?

Lucy Mushita: I didn’t really think about it. For me, child marriage was something from bygone days. I finished this manuscript in 1997 or 1998 and sat on it until it was published in 2008. When the 1998 and 2008 financial crises took place, I didn’t realise what was happening in Zimbabwe because I was not there. But recently, while talking to my niece, Tadiwa, she told me a man had married his daughter off to his best friend during those times. For me, the practice of child marriage was history; Chinongwa’s story is, after all, set in the early twentieth century. It seemed to be something that came about because of colonisation. I was convinced that it was no longer a practice of the current era. And sadly yet it is.

My take is that as long as there is no debate or conversation, nothing will change. As long as there is no debate about how this patriarchal system came to be—why, for instance, you need to give a family cows to prove that you love a woman—nothing will change. Today, I think we could use the word ‘grooming’. Little girls are groomed for marriage from birth. We are thinking, ‘Oh she’s beautiful’, and not how intelligent she is and what profession she can pursue. I don’t know about your generation but for us, we were told things like, if you walked very fast as if you were possessed, no man would marry you. Or if you do this or that, no man will marry you. So everything you did, you had to make sure that you were doing it so a man would desire you. How can we get to a place where women realise that they don’t need this?

And you still have people in Zimbabwe who will marry a second woman because the first one didn’t have sons, because girls are deemed as not being as valuable. Even as the girl is looking after them. How many of these families are looked after by their boys? It’s the girls, or the son’s wife, who usually do the caring work.

The JRB: I’d like to talk a little bit about style. Your writing is very accessible and simple. Was it something that you intentionally tried to do, perhaps to reach a wider audience? Or was it just that you wanted to maintain the flow and the characterisation without getting too verbose or metaphorical?

Lucy Mushita: Ah, it’s very interesting what you’re saying. Because I remember many people asking me how the Zimbabwean book launch went, and I told them that there were some kickass women there who understood the book more than anybody I’d encountered before. And I think this is because you, as Zimbabweans, knew what I was talking about. A lot of people here in France will say they found it very difficult to get into the book. And that’s probably because it is something so contextually foreign to them.

The JRB: You’re local to multiple places and people (having lived in Zimbabwe, France, Australia and the United States). What is it like to straddle these different worlds, and to have readers who engage with your work from so many different positions?

Lucy Mushita: I suppose there’s a kind of dissociation that must happen. But it’s also very interesting for me as a writer to say, ‘Ah, so this is how you see it’. One person told me that I had gone into the Bible to come up with the story, which I thought was a bit rich. I remember speaking to an Australian of Aboriginal descent, and he was talking to me about the themes of colonialism in the book and how they related to their own experiences. And then a Kenyan friend was telling me about what happened in Kenya, which is similar to the Zimbabwean context. And then I had an American who asked, ‘Why didn’t the women just gang up and bash the guy?’ So yes, it’s very, very different. It’s interesting to see how people interpret events depending on where they are coming from.

The JRB: Thank you so much for this time, but I wanted also to give you the floor in case you have anything you feel we haven’t touched on, or that would be enriching to the interview to add?

Lucy Mushita: No, it’s been a very good interview. I think you are the first person from Zimbabwe who has interviewed me, who understands the context of the book. That is also one of the reasons I really wanted this book to come out in Zimbabwe. Because it was a painful thing to think that this book was in its second edition in French but had never been published in Zimbabwe. It’s very important to get our books published back at home, especially when we are talking about issues in Zimbabwe. Especially issues that impact women as much as this, because it really is a human rights issue.

- Fungai Machirori is a Zimbabwean writer, researcher and commentator interested in African literary and digital spaces. You can learn more about her work at her website.

One thought on “‘It’s very important to get our books published back at home’—Fungai Machirori interviews Lucy Mushita on her novel Chinongwa”