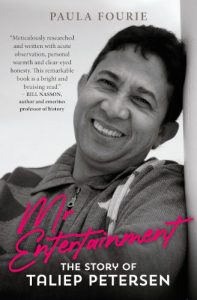

Carina Venter reviews Paula Fourie’s Mr Entertainment: The Story of Taliep Petersen, finding a life that encompasses a country and its histories.

Mr Entertainment: The Story of Taliep Petersen

Paula Fourie

Lapa, 2022

Mr Entertainment is a book about embracing:

the clipped exuberance of the life of Taliep Petersen;

the extremes of a young singer collaborating with Broadway artists while the only Hollywood he knew of ‘was a furniture store in Long Street’;

Taliep’s many identities, Malay, Coloured, South African, Afrikaans, cover artist, guitarist, tenor, arranger, composer, collaborator;

the contradictions of invented autobiographical moments and opportunities denied;

the women who sang, sacrificed, substituted, loved, mothered, grandmothered, cooked, cared, worshipped;

the discomforts of the white biographer, Paula Fourie, wanting to speak in Afrikaans to Taliep’s Afrikaans-speaking family;

the family who frequently address her in English in an essential denial of something shared.

Paula Fourie writes Taliep Petersen’s life as encompassing a country and its histories. It is a life that stretches back mythically to before 1488 and the Western ‘discovery’ of the Cape; jolts forward to District Six where Petersen was raised and the place that would sustain his best-known musical triumphs; charts the ever-more ambitious geographical and artistic trajectories the man nicknamed ‘Balle’ carried to Kuala Lumpur, New York, London, Vienna; and beams into the living-rooms of post-apartheid South Africa on kykNET programmes such as Afrikaans Idols, featuring Mr Entertainment turned judge.

A book about embrace, but also about the chokehold of segregation and socioeconomic deprivation. Around the music, violence lurks everywhere: underneath the ‘satiny and explosively bright’ uniforms of the then-named Cape Coon Carnival troupes carrying weapons; in the Star Bioscope, where a performer could be yanked from the stage by dogs at the bidding of the gang in charge; in the house where Petersen grew up and the intimate relationships he later had with women; in the systematic demolition of District Six, which couldn’t demolish what that place would come to represent; in the prisons where Petersen would coach carnival troupes; in the bedroom where Najwa Dirk, Petersen’s second wife, delivered a near-fatal knife wound; in Fourie’s dreams about the book she is writing. Fourie notes early on that the reader can skip between the seventy-one chapters at random. But the narration is chronological and hard to conceive of otherwise. In this finely written biography, there is consolation in the slowness of chronology, as if the devastating end on 16 December 2006 can be suspended into a future delayed, to revel in the sonic fusion of the multiracial performance spaces where Petersen found his voice and place.

The portals onto Petersen’s life are many: interviews with his father, Mogamat Ladien; his siblings, among them Tagmieda, who of everyone perhaps knew Petersen best; his children, Natasha, Jawaahier, A’eesha, Ashur, Fatiema, and Zaynab; his first wife, Valma Anders; artists and collaborators who peopled his music, among them Paul Petersen, Terry Fortune, Howard Links and David Kramer. There are also Petersen’s scrapbooks with their purple pages, newspapers, photographs and, of course, the music.

Petersen’s musical story begins, like so many musical stories of acclaim, with childhood prizes, eagerly recollected by a glowing parent. He won the juvenile sentimental category of the Coon Carnival at the age of six, and continued to pull off this feat year after year, achieving second place only because it wasn’t appropriate to appoint the same winner each year. His father recalls these early public triumphs, such as the story of a young Petersen roped in at the last minute to substitute for another in Coon captain Mogamat’s troop. Petersen remembers the story differently. His memory is of a threatening father who wakes him in the dead of night, having dispatched a soloist with a ‘klap’, and subsequently needing a substitute singer.

Fourie doesn’t conceal the echoes of generationally transmitted violence. Valma Anders recalls how a young and fiery Petersen could ‘bang’ her ‘with a fist’. ‘Petersen was ’n harde man,’ she recalls later on in the book, now as Madeegha, the name she took upon converting to Islam, Petersen’s faith. But it matters who is doing the remembering in Mr Entertainment. Dave Bestman, who worked alongside Petersen on their first and only musical, Carnival à la District 6, recalls him as ‘a softy’ who ‘was never strict’. Paul Hanmer remembers that he could be ‘scathing’ although there was never physical violence. Even Petersen remembers with palpable dislike an earlier version of himself: ‘As ekkie Taliep moet kry van dertig jaar of twintig jaar geliede … dan sal ek hom self gemoer het.’

One of the many invaluable aspects of Mr Entertainment is its meticulous documentation, especially the portrait of a lesser-known Petersen, prior to the big-name musicals and the turn to television. Following early successes in and around District Six, mostly as a star performer in his father’s Darktown Strutters, Petersen shot to local fame in 1968 when, in front of a five-thousand-strong crowd, he was crowned Mr Entertainment. Local, in this context, was enclosed by the restrictions of apartheid. The audience was ‘Coloured’, the competition ‘Coloured’, and Taliep Petersen would not have registered as a name worth noting outside the state-enforced confines of Coloured culture for Coloured people.

Another distinguishing feature of these early opportunities was the regularity with which Petersen performed covers. In the early seventies, he featured on acoustic guitar with the Continental Strings, a group playing mostly Spanish music. Around the same time, he toured with Alfred Herbert’s African Follies and subsequently the Minstrel Follies in shows that pandered to the ‘African exotic appeal’. By the mid-seventies, he had a first single released by EMI, featuring ‘Sweet Sunshine’ and the B-side, ‘Friends and Brothers’, and had starred in yet another ‘Afro-variety’ show, Reach for the Stars. Petersen rapidly developed a reputation on the cabaret circuit performing popular covers, a form of light entertainment consumed by well-heeled white hotel guests. It culminated in the formation of Sapphyre in the early nineteen-eighties. Fronted by Petersen, Sapphyre became the first ‘Coloured’ band to be hired by the Southern Sun hotel group.

There is something about the seminal role performing covers played in the making of Taliep Petersen that mirrors the elusiveness of this remarkable man’s story. His voice had to sing the music of others, as his body had to obey the laws of apartheid. But here, too, Fourie finds subversion. The covers could also amount to a refusal of the imposed confinement of separate development, the separate songs, ethnicities, cultures and traditions condemning South Africans to racially segregated and legally guarded reserves of sound, space and much else besides. Petersen sang covers. In doing so, he crossed boundaries whose physical crossing was denied unpermitted bodies like his.

If Fourie’s reading is eager to find resistance in Petersen’s embrace of an industry that turns on the entertainment of white patrons in plush hotels—a manner of reading that is the sine qua non of post-apartheid reconstruction hungry for histories of subversion of that essentially white evil that differently and unequally deformed all of us—it is also a more than credible decision to write Petersen’s life beyond the rigid boundaries of high and low, art and entertainment, other and self. It’s an attempt realistically rooted in the fraught negotiations of invented tradition and state-inflicted identity. As Hanmer, youngest member of Sapphyre and himself no stranger to such questions, remembers about his father’s insistent dissociation from the Coon Carnival and Malay choirs:

Because, you know, die ‘kleurlinge‘, or ‘people of colour’, you know, just because we find ourselves behind the coloured fence, it doesn’t mean we’re a tribe with any special attributes.

It was meeting theatremakers Des and Dawn Lindberg in 1973 that drew Petersen closer to the genre that arguably defined his career. He subsequently played in the 1974 production of the ‘irreverent and anti-establishment’ musical, Hair, which, like the Lindberg’s staging of Godspell a year earlier, opened in in Maseru, a short trip across the border for South African audiences but beyond the reach of apartheid censors. Pippin, produced by the Lindbergs, followed in 1975, and shortly after yet another Lindberg collaboration appeared, Sing Out. But Mr Entertainment knew that he didn’t simply want to sing the songs of others. His first attempt to introduce material from District Six came in Sing Out, and met with scorn. ‘Then he blew it’, declared Charles Stoneman in an otherwise positive review. ‘His audience’, patronised the critic, ‘wanted to forget or laugh about their troubles, not be reminded of them.’

So angered was Petersen by this criticism that he cut out Stoneman’s offending lines before adding the cleaned-up review to his scrapbook. When, some years later, he wrote the first of several draft scripts for Carnival à la District 6, the effects of Stoneman’s critique are evident, stripped of the darker workings of apartheid socioeconomic deprivation. Bestman remembers his first reaction upon reading the script: ‘“No, no, no, no, this is not it. Hey, man! District Six is kill, murder, rape, those type of things, man.” So he got cross with me, tore the script up, threw it away.’ After a fifth attempt, the pair was happy. In 1979, the musical opened in a Swaziland Holiday Inn. The trajectory of three subsequent stage versions of Carnival à la District 6 is the trajectory of a man writing his voice and place into sound, a man gradually emancipated from the confinement of covers and the cleaned-up narratives of life under apartheid. The final version seemingly never saw the stage (several earlier versions were performed in and around South Africa), but stubbornly refused the pat trope of the ‘happy black’ that so thrilled audiences of Ipi Tombi, the Bertha Egnos musical that initially put Petersen onto the idea of Carnival.

Midway through, Mr Entertainment arrives at the collaboration that would define much of Petersen’s legacy. David Kramer remembers Petersen first of all as a friend—a friend who carried inside of him a detailed map of District Six. Together, Petersen and Kramer excavated this map, set it to sound in District Six: The Musical. Their work is not without the questions that plague such collaborations, subjected to the unequal privileges of apartheid. The questions must be asked, and Fourie asks them. Why was Petersen not initially listed as one of the producers of District Six: The Musical? Who wrote what and who got credited for what? Who extracted what from whom? The pair co-created several musicals, following up District Six: The Musical with Fairyland, Crooners, Poison, Kat and the Kings, and Ghoema. At least initially, Kramer was mostly responsible for scriptwriting, Petersen for remembering and the music. By the time they created the character of Kat Diamond, a clear division of labour had emerged, although they would formally continue to assert joint authorship of everything. Contrary to suggestions by critics that Petersen wrote and Kramer furnished the white hand of opportunity and possibly opportunism, theirs were, suggests Fourie, a mutually complementary collaboration. As Petersen himself summed it up: ‘hy is meer as ’n partner en vriend, hy is soos my broer.’

By the time they worked on Kat, Kramer had access to District 6, not only through his long acquaintance with Petersen, but through musicians, actors and friends with whom he had built lasting relationships. He conducted interviews and wrote the script, while Petersen took care of the music. The fifteen songs that resulted mark something of a musical apotheosis for Petersen, sounding District Six through ‘the disparate elements of songs that he had to keep in his mind and body; … [drawing] on his capacity to sound any song through the lens of any other.’ Kat and the Kings fetched an FNB-Vita Award for Best Musical and played to audiences around a newly liberated South Africa, whence it travelled to London’s Tricycle Theatre, New York and Europe. Initially, in its local and lean design for a stage ‘no bigger than a couple of tables pushed together’, Kat was a musical propelled not by grand stage props but by story and sound, replete with Jody Abrahams swinging with a rope from atop a piano into the audience. This ‘do-it-yourself theatre’, stripped of the expensive slick of a West End production, would not do, neither for the theatrical demands of London audiences nor for the strict health and safety measures of theatre-making with access to resources. This led to a second makeover by South African-born Saul Radomsky upon its arrival in London (the first having been accomplished by Kramer and Petersen when they introduced the character of Lucy Dixon). It mostly worked. ‘The cast has enough energy to power up the Albert Hall’, gushed one reviewer. But there was also criticism, not least in response to the musical’s blithe ‘stuff politics, let’s dance’ message.

Meanwhile, Kat continued its local and international success and Petersen became involved in television, initially upon the prompting of Mynie Grové, who helped him understand this was the medium that would carry him into the consciousness of Afrikaans-speaking white South Africans. Following an extended stint in television, where Petersen worked closely with Herman Binge, he joined forces with Kramer one last time for a musical that opened in March 2005 at the Klein Karoo Nasionale Kunstefees.

Ghoema marked Petersen’s increasing interest in sounding his Afrikaans-speaking roots through the syncretic harmonies of Nederlandsliedjies, moppies, ghoemaliedjies, and the creolised songs which the Federasie van Afrikaanse Kultuurvereniginge standardised into seemingly unsullied Afrikaner folk music. Petersen was reclaiming the indisputably hybrid origins of these songs, and with it his own Afrikaans heritage. Ghoema is one of few instances where Fourie sounds a critically cautionary note in relation to the creative material in front of her. Her criticism hinges on half a story told. Ghoema is the ‘frenetic playing and dancing on stage’, packaged for painless consumption in the happy stories of shared heritage narrated by its MCs, Hot and Tot. Vanquished are the indisputably violent roots, the devastation wrought by colonialism and apartheid, of which the stage introduction earned Petersen the criticism of Stoneman back in 1974.

Najwa Dirk gradually insinuated herself into Petersen’s life. This choice of verb echoes those used by interviewees: ‘crept in’, ‘ wormed herself in’, ‘sink’ her ‘nails’ into Petersen. The picture that emerges from these years, the late nineties and early two-thousands, is one of complicated domestic life. There was a rigid roster, as if Petersen could arrange the dissonances of a combined household with six children and his second wife into a harmonious routine: return from school, lunch, Muslim school, dinner at five o’clock at which Petersen asked each child about their day, prayers, homework, one hour leisure time, Petersen reading to everyone from the Cape Argus, Petersen with an impromptu quiz on the news items just covered, Petersen putting each child to bed.

Dirk could smother with love. Initially there were lavish gifts. Later, she smothered with food, loading up dinner plates to distract children and siblings from speaking with Petersen. Relationships became strained. There were kicks beneath the table aimed at Petersen’s children, mouldy bread with fish paste packed into lunch boxes, sharp words, accusations. But Fourie, like some of her interviewees, is careful not to paint Dirk as the ‘quintessentially evil stepmother’. She battled with mental health, vulnerability, insecurity, jealousy, fear of losing Petersen to another. Yet it should be pointed out that Fourie refuses her the power of direct speech in Petersen’s biography. Beyond the denials documented in court papers and hearings, Dirk’s own account is a portal denied.

Petersen’s final two days were filled with anomalies. Is it the work of retrospect, the wondrous desperation of unpacking again and again someone’s final hours, noticing what was always there but suddenly shocked by the retrospective knowledge of loss? A striking inversion unfolded on 15 December 2006. Petersen is preparing for an evening show at the Wynberg Luxurama, where he had so many early successes. His fourteen-year-old son, Ashur, walks into his studio with the request to appear on stage that evening with his dad. Petersen says no, then, changing his mind, issues Ashur with a sheet of music and a guitar. There is in this recollection no trace of the father whose figure looms over a six-year-old Petersen, exuding equal parts threat and invitation to sing. Perhaps overcome by the moment, Ashur blew the words that night on stage with his father. Uncharacteristically, Petersen’s response was not anger, recalls Ashur to Fourie: ‘He’s like, it’s okay, just carry on! […] and then he sings with me.’

Fourie reveals her own battles in writing Petersen’s death. It felt, she says, ‘as if I am letting it onto these safe pages, making it happen all over again. But books are marvellous things, capable, I believe, of tiny resurrections. One can always turn, again, and again, and again, to the first page.’ If books accomplish tiny resurrections, Petersen, too, had his own recipe for such tiny miracles imagined through other lives. As with his music, which steadily emerged from the administered mimicry of covers, his gift for reinvention wasn’t restricted to plot, arrangement and composition. He could misremember and reconstruct: roles in Godspell, Jesus Christ Superstar and The Black Mikado, a Sarie award for best male vocalist in 1979 which actually went to Anton Goosen, and fifteen years later, in 1994, the claim in an interview that he sold all his possessions to study music in England. What to make of these fabrications? They are by no means unusual fare, the artist indulging the temptations of reinvention and inflation. But, as Fourie points out, they resonate with poignancy in a context marked by what had been denied Petersen on account of skin colour, as if Petersen wanted simultaneously to imagine the life he would have lived in another South Africa free from apartheid. A life encompassing not only a country and its histories, then, but the many possible countries and histories that could have been.

Fourie refuses to give up the story of Taliep Petersen to the insatiable demands of a research economy propelled by stream-of-publication outputs, a quick and consumable highlights package of the life of Mr Entertainment. It is a book painstakingly researched, commencing with a doctoral studies in 2011 and culminating in a movingly-written, well-crafted piece of prose. A slow labour of care and commitment that does justice to ‘die harde man’ who dreamed in Afrikaans and his ‘supple voice with a broad smile at its edges’.

- Carina Venter is lecturer in Musicology at Stellenbosch University and chair of the South African Society for Research in Music. She holds degrees in music and musicology from the universities of Pretoria, Stellenbosch and Oxford. Her research interests centre on music, violence, decolonial thought, and discourses of apartheid and colonialism.