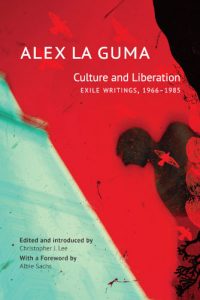

Culture and Liberation: Exile Writings, 1966–1985

Alex La Guma

Edited by Christopher J Lee

Seagull Books

1966 was an interesting year. Future Trump supporters were burning Beatles records. Muhammad Ali was refusing to be drafted into his country’s foolish vanity war. Kwame Nkrumah flew off for a visit to North Vietnam and China, and found himself locked out of Ghana. England won the World Cup, inheriting a future of heightened dreams and shattered hopes forever after. And, no less notably, Dimitri Tsafendas gave his name to a masterful sort of knifery.

Amid all these fantastic developments, a writer and his family slipped quietly from South Africa’s shores. The writer would never set foot in his homeland again.

The unhomed writer is an alienated figure. Exile—a word denoting outsiderness, but also a word which conjures up other words: Expulsion. Exit. Removal. Limbo. Waiting. Banishment. These are states of being outside, of enforced separation from the collective. The story of exile is by its nature an untold story—a story of absence that can only be explained afterwards, if at all. The word is a portmanteau for a set of experiences that exceed containment. Nat Nakasa’s story of exile is not the same as Bessie Head’s. Miriam Makeba’s story of exile is not Arthur Nortje’s, nor is Lewis Nkosi’s story the same as Letta Mbulu’s.

South African exilic writing flourished darkly in the long afternoon of apartheid. Among the varied company that made up the ranks of those flung to foreign corners, Alex La Guma, the writer who left South Africa in 1966, is probably the surest example of the exiled writer who disappears behind the story of his enforced wandering. La Guma died in 1985, barely into his sixties. His death reads as untimely and premature because of our lingering sense of the cruelty of dying away from home. It was, of course, the sorry fate of many of South Africa’s exiled artists to die abroad. Their absence from the long ongoing postapartheid (whose post-ness is increasingly reckoned to be ludicrous) means that their histories are often reduced to banal tragedies where exile signals a wounding flight to loneliness in unsuited climes, wasting descents into alcohol and drugs, the hastening of death via suicide or cancers or stopped hearts, and the sad fate of being forgotten in their homeland except for reminiscences that grow more dim and rheumy-eyed with each passing year. If they are lucky, perhaps one of their works may linger in the doldrums of the school setlist, given impoverished pedagogic readings by underpaid teachers to mostly disinterested students. Or they might be dutifully trotted out for a reheating in the literary equivalent of a garbage plate.

La Guma was one of the more prolific writers of that difficult period, but for years his name has served more as a politically expedient concept figure for the Black writer abroad, to be mentioned in bland conference papers and referenced in desultory commemorations when the state remembers its derelict Arts and Culture department. Most of La Guma’s fiction output is out of print: both the local works—A Walk in the Night (1962), And a Threefold Cord (1964) and The Stone-Country (1967)—and the later novels written during La Guma’s years abroad, In the Fog of the Seasons’ End (1972) and Time of the Butcherbird (1979). Some aspects of the neglect are puzzling—why, for example, has nobody attempted to make a screenplay from the stunningly dark A Walk in the Night?—whereas some omissions are the merciful closings of history on work that is not good (La Guma was a patchy crafter of short fiction). Of course, La Guma’s unabashed Marxism would always wilt with the ruling party’s decision to de-emphasise its inconvenient adolescent socialist leanings in the greed-for-all conservatism of the democracy years.

There are signs of change, however. A theatre performance based on the life of La Guma and his wife Blanche—Dance of La Gumas; Revolution, Rumba & Romance—just closed after a month’s run at the Artscape Theatre. La Guma has also inspired a consistent body of earnest and well-grounded scholarly study, much of it aimed at filling in the shadow in which the author’s career resides. Culture and Liberation: Exile Writings, 1966–1985 is a new and worthy entrant that does the good work of concretising some of La Guma’s disappearing archive. The editor, Christopher J Lee, has gathered together a weighty assortment of essays, reports, reviews, interviews and stories penned over the course of La Guma’s career. These ancillary texts, the sort of thing writers do out of interest, obligation and a need to support life, are a vital if unwieldy archive through which La Guma’s abiding preoccupations can be traced. Lee’s framing introduction wades into the thick of things, opening with a searching set of questions:

‘What does it mean to edit the work of the dead? What ethical considerations must be undertaken when collecting, revising and republishing the writing of those who have passed away and are unable to oversee and finish such tasks themselves?’

Lee’s words call to mind the perilous role of the editor-as-griot, cannibalising as they keep alive the stories of those no longer there to speak for themselves. Marshalling bits of a dead author’s oeuvre into a bricolage that speaks coherently to their wider intellectual project is always a presumptive regenerative project. The obvious risk of potentially bringing into the light of day what the author themselves might regard as the ephemera of their career hardly needs saying. Still, your story told by someone else—particularly someone working with scholarly patience to draw out connection and resonance—might in the end be richer than what the author themselves deems suitable.

Naturally, some shaping is necessary, because profligacy is diluting at best and wearisome at worst. Culture and Liberation runs to sixty-eight chapters and some six-hundred pages, a bit of a doorstop. It would take some daring to suggest that all the pieces are necessary, or indeed that such a distended collection is readable by non-specialised readers, but I am inclined to think charitably of the project behind this project: the editor, working with an unwieldy archive, has used the collection as a storage vessel against cultural forgetfulness. The threads of La Guma’s writing life are strung up for us clearly: his concern with the role of Coloured people in the struggle; the shaping of a political imaginary that spans from the postcolonial African countries through to Cuba and the Caribbean; the absurdity of the Western state machinations.

The nature of much of this material is that it dates when read from today’s perspective. La Guma is a workmanlike literary reviewer who writes with conviction, but with an occasionally heavy-footedness. There is a tedious review of Oswald Mbuyiseni Mtshali’s Sounds of a Cowhide Drum that is heavy going to get through because La Guma betrays a sentimentality towards Black life that becomes cloying. Witness, elsewhere, La Guma hurling a churlishly bien-pensant brickbat at Dennis Brutus for writing solipsistic poetry:

For the African people, poetry has little to do with books. It lives in their speech, in their songs, it reflects their attitudes towards life about them, it is common property … But for Brutus, everything, jail, exile, oppression, happiness, despair, happens to himself, the poet, only …

Because we have moved past many of the modes of writing that were the rage of their time, many of these pieces read a little leadenly. Of the rapier-sharp insight that lent La Guma’s published work much of its vitality, there are glimpses here and there. A wonderful tribute to Pablo Neruda or a trenchant bit of criticism on the state of South African writing are among the many gems, but their connections are breezy: without the editor’s helpful notes, it would be difficult to discern any great significance in many of the pieces of writing. While many of these pieces are historically interesting documents, they have no intimacy to them, for the most part. La Guma himself remains something of a ghostly figure behind all the print.

Read as a remembering catalogue of La Guma’s output, an infrastructure for further work, this collection makes sense. It is, above all, interesting in what it unearths, even though our interest may occasionally flag at the weight of it all.

- Editorial Advisory Panel member Wamuwi Mbao is an essayist, cultural critic and academic at Stellenbosch University. Follow him on Twitter.