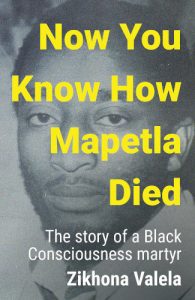

The JRB presents an excerpt from Zikhona Valela’s new book, Now You Know How Mapetla Died: The Story of a Black Consciousness Martyr.

Now You Know How Mapetla Died: The Story of a Black Consciousness Martyr

Zikhona Valela

Tafelberg, 2022

Read the excerpt:

The early years

The details of Mapetla Frank Mohapi’s life are elusive. It is difficult to write about him forty-five years after his death. This is after the deaths of his parents, many of his siblings and close friends, and so long after the events in which he was involved. Mapetla was born on 2 September 1947 in the rural village of Jozanashoek in what was known then as the Herschel district of the Eastern Cape.

Jozanashoek lies on the outskirts of Sterkspruit, which was the administrative headquarters of the district. The history of Herschel is fascinating and has been the subject of much academic research. Originally established as the Wittebergen Native Reserve, around the Wittebergen Methodist mission station where the novelist Olive Schreiner was born in 1855, it was annexed by the Cape Colony in 1866 and became the Herschel district in 1870. It was home to a multi-cultural Black community consisting of Basotho, AmaHlubi and other groups, as well as white missionaries and traders.

The area as we know it today—Joe Gqabi District Municipality, Eastern Cape, encompassing fifteen small towns—owes its ethnic diversity to various migrations and upheavals set in motion by conquest. Groups from various nations, including the Basotho, found a home in this district. Mapetla belonged to the Bahlakoana clan, which falls under the Bakoena, one of the parent groups that make up the Basotho.

According to oral history the Bahlakoana trace their ancestry to Lisema and are named after his first-born son, Mohlokoana, who lived circa 1570 along the Elands River in what is now the province of Mpumalanga. The growth of the clan over time led to its spreading southwards to present-day Prynnsberg, Free State. But in the early 19th century the Bahlakoana scattered, some moving north towards the Zambezi River and others further south to what is now the kingdom of Lesotho and the Eastern Cape.

By the 1830s, the district later known as Herschel was among the areas the Bahlakoana called home. This was in the middle of the 100 years of frontier wars between the Boers, the British and AmaRharhabe, AmaGcaleka, AmaMpondo, AmaMpondomise and other kingdoms in the Eastern Cape. The BaTlokwa king Sekonyela and his followers settled in the district after suffering defeat by King Moshoeshoe I’s forces in the 1850s.

The mid-19th century saw the rise of a prosperous rural community that was self-sustaining despite the often unforgiving, dry and drought-prone landscape of most of the area. This is one of the reasons that Richard Mohapi Mapetla relocated from Maseru in Lesotho to Herschel. He left his homeland as a result of a family dispute. The reasons for this dispute are lost, but considering that Mohapi Mapetla dropped his surname, things must have been bad.

Soon, two more Mapetla brothers joined Mohapi and they also dropped their original surname. Richard Mohapi Mapetla and his brothers went by the surname Mohapi from then onwards and their children took on this surname. Mohapi’s sons, one of them being Mapetla’s father, Mphatsoe Wycliff, tried to mend the fracture by using the original family name as a first name for their children—hence Frank Mapetla Mohapi, who grew to be one of the prominent figures in the Black Consciousness Movement (BCM).

Mapetla was also named Phuthiatsana, after the river in the Berea district of Lesotho that forms a border with the Free State, much of which formed part of the kingdom of Lesotho until colonial conquest resulted in theft of the land. Although it is a remote and isolated area, there is a large archive of writing on Herschel, much of which relates to protest movements. Some of the most significant women’s protests of the early 20th century happened there. These were staged by the Amafelandawonye—women who boycotted white traders’ stores in protest against high food prices.

The turn of the century saw a decline in the prosperity of the peasantry as a result of colonial land and taxation policies, which made subsistence difficult and were intended to compel Black men to look for work on the mines. This disrupted traditional family structures and divisions of labour. In the absence of men, women took the lead.

However, as late as the 1930s, a substantial Black and rural middle class was present in Herschel district. At the time of the passing of the Natives Representation Act in 1936, a measure that removed African voters from the common roll in the Cape, there were as many as 450 African voters in Herschel, for whom there was an income qualification. They had a significant political influence in the local constituency until their disenfranchisement, which was pushed through by the United Party government of General Jan Smuts.

Along with Mapetla, Herschel was the birthplace of a number of prominent political personalities, including Solomzi Ashby Peter (AP) Mda, one of the architects of the ‘Africanist’ tradition that later gave rise to the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC), and the father of the novelist Zakes Mda, a contemporary of Mapetla who spent a few years at school in Sterkspruit. Mapetla cited the elder Mda as one of his political influences.

Mapetla was born in what AP Mda called ‘the golden age of schemers and planners’, which gave rise to apartheid. His birth on 2 September 1947 came only eight months before the upset victory on 26 May 1948 of the National Party alliance under Dr DF Malan. No one had anticipated General Smuts’s and the United Party’s loss, not even the NP itself, which had its eye on taking power a by 1953 at the earliest.

In piecing together the elusive details of Mapetla’s life, what is certain is that he came from a community of resistors and was born at a crucial time in history that would lead to his own entry to the forefront of the fight for Black liberation.

Mapetla was the third of eight children. His four brothers were Mpoko, Mohapi, (Mapetla was born next), Kekane and Letsela, who was the last born among the children. One of his three sisters, Khahliso, the fifth born of the Mohapi siblings sadly passed away as a child. Two of his sisters, Lihlare Mohapi and Mabuasele Mohapi-Segopa (born one after the other) are still alive. Mapetla’s mother, Manoe, was a teacher at Jozanashoek Primary School and his father, Mphatsoe Wycliff, was a clerk of the magistrate’s court in Sterkspruit.

Mapetla’s colleagues and surviving relatives recall a person who spoke only when he felt it necessary to do so. Mapetla was obsessed with neatness and took pride in looking presentable and constantly kept a neat space around him. His sister Lihlare remembers him as someone who showed leadership and above all care for his younger siblings, particularly his two sisters, whom he taught chores around the home. Perhaps as the youngest of the three older boys he was left to do the ‘tedious’ work (for a boy) of mentoring his little sisters while his parents were at work.

The sexual division of labour between boys and girls means bonding time is often limited. This comes through in Lihlare’s memories of her brother. The bonds that could have formed and solidified along the shared realities of adulthood, parenting or marriage have been forever denied to them.

- Zikhona Valela is an historian. She has contributed writing for various publications including New Frame, The Johannesburg Review of Books and the Mail & Guardian. She holds a MA in History from Rhodes University. This is her first book. She lives in Johannesburg.

~~~

Publisher information

Mapetla Mohapi was a leading member of the Black Consciousness Movement, and the first to die in detention in 1976. Police produced a ‘suicide note’. The note was later confirmed by a British expert as a forgery. Since then, his wife Nohle has worked tirelessly for justice.

Zikhona Valela traces the politics of the time, the convergence of biographies that led to the brutal and tragic death of Mapetla Mohapi, and the effects on Nohle and the Mohapi family.

A shocking and necessary book.

This is a brave attempt by Zikhona Valela to document the life of this giant. I hope that she will come across my review of her book.