Donald Parenzee died on 21 April 2022 at the age of seventy-three. Mark Espin reflects on his work and life.

Dedicated to Making Things: Donald Parenzee

In an interview with Robert Berold in 2000, Donald Parenzee explained aspects of his work as an architect, citing a particular experience encountered while working on a project situated within a rural community along the west coast of the Cape. Having recognised the unique conditions that prevailed, he describes an innovative approach which involved having ‘to perceive the building as it came up out of the ground, bearing in mind that people were learning to work with the material as the construction proceeded’. The organic and speculative qualities at the heart of this approach were to mark much of Parenzee’s work, whether in designing built structures, participating in cultural initiatives or in his approach to the writing of poetry. Although there were several years between the two published volumes in which his work appears, there is an underlying unity in the poems, especially as many of them can be defined as speculative in contemplating any form of resolution offered or proposed within them.

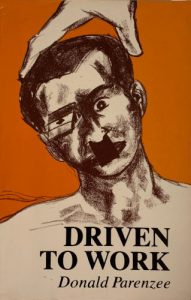

The first book, Driven to Work, was published by Ravan Press in 1985 and is, undeniably, influenced by the tenor of the time, as is obvious from the poems directed at the forms of oppression and subjugation suffered by those living under the apartheid regime. The poems, however, stubbornly resist merely becoming a catalogue of maudlin and sombre reportage, and are instead distinguished by inventive and subtle inflections, ensuring nuanced dimensions rather than being nothing other than blunt condemnations. One striking example of this is ‘Anger’, in which verb and adjective are finely honed to convey an unequivocally emotional response to the plight of working people, yet never faltering in the employment of the evocative image. The subject of the first poem in this volume is made explicit in its title, ‘Detention of an Ordinary Girl’. In the first stanza the speaker declares that what her probable interrogation and torture will reveal is ‘the pattern/we had traced upon her skin’. These lines insist on claiming an ethical essence in the face of the physical and psychological violation that will be a consequence of her detention. What this may also allude to is the impact of a particular conscience-making process the girl has undergone.

It is not implausible that this may be a reference to the conscientisation that Parenzee had himself experienced, a pattern of thought that he developed within the South Peninsula Education Fellowship, an affiliate of the New Unity Movement, an organisation with a significant progressive tradition. In this organisation, Parenzee gained access to many books and other resources informed by broadly leftist sensibilities. In his interview with Berold he credits the influence of Dawood Parker, who maintained this library in his flat, and confirms that his exposure to these texts resulted in an interest in ‘Neruda, Brecht, Ritsos, Hikmet … socialist poets. I was surrounded by socialist politics, so the politics and the poetry were aspects of the same thing in a way’. The inspiration provided by these poets and the work of others, such as the anti-Stalinist Eastern European writers who had begun to appear in English in the nineteen-seventies and eighties, is clear in Parenzee’s work. This is most obviously apparent in the quotations from Ritsos used as epigraphs at the head of each section. The influence of poets such as Zbigniew Herbert and Miroslav Holub is present too, in the detached yet scrupulously observant speaking voice deployed in many poems. It is a speaking voice which, while often ironic, never lapses into the dispassionate or the irredeemably cynical, remaining intent upon being attentive to the world around it, whether recounting the tumultuous or the quotidian.

The latter is evident in a poem dedicated to Parenzee’s daughter, Megan, which describes a job interview that evidently proved to be an unpleasant experience. The closing lines, though, include the following declaration, which not only clarifies the dedication but also establishes a fundamental separation from technocratic and financial imperatives which can be attributed to the anonymous interviewer:

… your arms, as subtle as paper chains, fall

in the minutes before you leave

into sleep, lightly from my shoulders,

trusting that I shall never run, never desert to freedom.

And this interviewer, his childsface

distorted with horrific, secret lust,

I shall repay with portraits

of truths in children’s minds.

One of the most regrettable aspects of our society, more than three decades later, is that it is clear that those to have benefited most unmistakably from our hard-won democracy are those who quite explicitly and unashamedly covet the technocratic and the commercial.

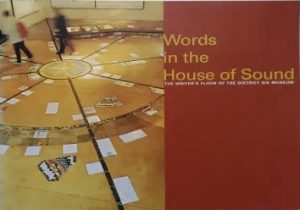

The second volume to include Parenzee’s poems was a collaborative publication, No Free Sleeping, which included the work of Alan Finlay and Vonani Bila, published by Botsotso Publishers in 1998. Many of the poems were responses to what has become known as the period of transition, with one an incisive commentary that addresses the murder of Chris Hani and another, ‘Making Things’, that charts the ethos of a new society. In the intervening years between the two publications, Parenzee had left the Peninsula Technikon where he had taught architecture and begun work as a curator at the District Six Museum. During this time, he had also worked with a group of younger artists across disciplines, culminating in a production featuring music, dance and poetry to commemorate the notorious Trojan Horse incident of state violence that occurred in Athlone in the latter part of the nineteen-eighties. When one of this group, Ralton Praah, died of suicide not long after the advent of the democratic dispensation, Parenzee dedicated a poem to him that included an eloquent and powerful indictment of the increasing shift to a society dominated by the market and other economic determinants.

In 2000 he curated a unique project at the Museum. The book that emerged out of this work was Words in the House of Sound: The Writer’s Floor of the District Six Museum, which includes extracts from his poem ‘For Ralton’. In the body of recent South African poetry, it remains one of the most cogent denunciations of the betrayal of the political struggle. It is a plaintive appeal for a rejection of the commodification of life which has, unfortunately, become even more prevalent in recent years:

… Now in the seventh season of the nineties

the winter wind has taken

another friend; a mild and subtle

generous wind calls us …

… Oh City,

Now the Sweet Things hold the corner shop

of Manenberg way into the night,

jeering at the lovers who huddle by,

their arms locked under loosened clothes.

Away into the same wind they’ll be blown,

out and beyond the Hottentots

this time next decade while here

we kneel obeisance to the New City.

Oh City turn yourself around now

with some sudden grace, gaze deeply

at your history: the wiles of hands

are fingering your pockets

for a hot feel of success, and you’ll not

call your children back to a void

where your heart used to be …

The wind has indeed taken another friend. Parenzee died on 21 April 2022 at the age of seventy-three, several months after a diagnosis of oesophageal cancer. He has left a formidable literary legacy despite not always garnering the attention of scholars and anthologists that he should have. Having dedicated much of his life to the pursuit of the poetic and the just, it is appropriate that he is immediately thought of when one reads Derek Walcott’s ‘Sea Canes’, a tribute to friends who have died, and it is possible that those who treasure Parenzee’s life, and his work, may be consoled by Walcott’s affirmations in his closing lines:

… out of what is lost grows something stronger

that has the rational radiance of stone,

enduring moonlight, further than despair,

strong as the wind, that through dividing canes

brings those we love before us, as they were,

with faults and all, not nobler, just there.

- Mark Espin was born in Cape Town in 1964. He teaches in the English Department at the University of the Western Cape and lives in Athlone. His self-published pamphlet, April in Blank Verse (2021), is available at Surplus Books.