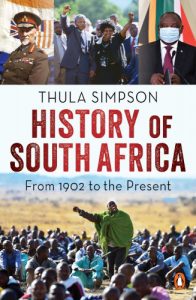

The JRB presents an exclusive excerpt from Thula Simpson’s new book History of South Africa.

History of South Africa: From 1902 to the Present

Thula Simpson

Penguin Random House, 2021

Read the excerpt:

From 2 p.m. on 7 July [2021], the SAPS’s Major General Nonhlanhla Zulu negotiated with Zuma at Nkandla, and her discussions with him continued until just after 11.15 p.m. when a convoy of about fifty police vehicles approaching slowly from Eshowe came into view. Zuma’s Presidential Protection Service convoy promptly departed in the opposite direction, and he was admitted to Estcourt Correctional Centre at about 2.20 a.m.

Traffic reports on the afternoon of 8 July noted that demonstrators demanding Zuma’s release had closed the M4, N2 and R102 on KwaZulu-Natal’s north coast. At the time, ANC members in the province were engaged in feverish activity on WhatsApp and Telegram, coordinating further protests. Participants on ‘Shutdown eThekwini’, a WhatsApp group established that day, discussed possible targets in Durban, including highways and shops associated with ‘White Monopoly Capital’.

Details of protests were then disseminated on Facebook and Twitter. This included @DZumaSambudla, the Twitter handle of Zuma’s daughter Duduzile Zuma-Sambudla. On 9 July, her account posted a ‘Shut Down KZN’ flyer calling for closures of roads, factories, shops and government until her father was released. As the day progressed, she circulated images of blockaded roads and vehicles being stoned and burnt, accompanying them with the words ‘we see you’ and ‘Amandla!’

The N3 Toll Route was the most strategically sensitive stretch of road in the country, for it linked the busiest port, Durban, with the economic powerhouse of Gauteng. On the evening of 9 July, twenty-four trucks were torched on the N3, and two on the main alternative route, the R103. The following morning saw videos circulating online of cars heading to Gauteng to demand Zuma’s release, while anonymous social media posts called for a total shutdown beginning on Monday. The evening of Saturday 10 July saw stores and vehicles looted and burnt in parts of Johannesburg, including the CBD, Malvern, Jeppestown, Denver and Wynberg.

That was the context in which Ramaphosa addressed the nation the following evening, but while he devoted a section of his speech to condemning ‘increasingly violent protests … based on ethnic mobilisation’, he offered no action, and instead left it to ‘God … to bless South Africa and protect her people’.

That evening saw mass looting in many other parts of the greater Durban area, including the CBD, Cornubia, KwaMashu, Mariannhill, New Germany, Phoenix, Pinetown and Verulam. Overwhelmed SAPS teams called for support from off-duty and on-leave counterparts, neighbourhood watch WhatsApp groups lit up with alerts and calls to organise, and Durban’s Chamber of Commerce and Industry issued an urgent appeal to the central government for an immediate troop deployment. In response, Ramaphosa authorised ‘Operation Prosper’ that night, involving the dispatch of 2,500 SANDF soldiers.

On the morning of 12 July, malls were burning all over Durban, and the police appealed for support from security companies, but the latter were also stretched. Footage of the looting was broadcast across the world that morning. The images showed that the participants covered a wide spectrum, from giggling preteens to portly gogos, while the goods were carted into vehicles that included double-cab bakkies, forklift trucks, Mercedes-Benzes and Range Rovers.

The other main public response to the crumbling of the police lines involved neighbourhood watches and community policing forums (CPFs) calling for the organisation of barricades. In response, residents, private security companies and individual SAPS members formed human shields around businesses and strategic points in many areas.

Ramaphosa addressed the nation again that evening, and warned that ‘these disruptions will cost lives by cutting off supply chains’. As he spoke, eNCA split the screen with live coverage of the South African National Blood Service (SANBS) centre at Durban’s Queensmead Mall being looted.

The images reflected the fact that the SANDF reinforcements had not arrived. The worst conflict that evening occurred in parts of Durban and Pietermaritzburg that were classified as Indian under the Group Areas Act, and which, owing to apartheid-era urban planning, were abutted by African townships. The post-apartheid years had seen significant desegregation, and some of the community patrols established on 12 July included black and coloured homeowners, and even shack dwellers from adjacent areas.

There had been bloodshed in Phoenix during the day, following clashes that spread after four men in a bakkie with no registration plates opened fire when patrollers tried to stop them at a checkpoint. The patrollers returned fire, killing a passenger. After dark, patrollers in Phoenix smashed and torched passing vehicles, and ambushed suspected looters. Similarly, in Chatsworth, residents and security guards fought to prevent people from the Bottlebrush squatter camp from entering the main shopping centre. In both areas, patrollers were targeted by drive-by shooters, causing further deaths.

The nation woke on 13 July to reports of white militiamen stopping and even shooting at black passengers. Some commentators drew parallels with the apartheid era, but the phenomenon had spread sufficiently widely to defy neat racial categorisations. The 12th had seen crowds of looters roving from mall to mall in Soweto, contributing to a stampede at Ndofaya Mall that killed at least ten people. As the scenes were broadcast on television, residents in Pimville mobilised through WhatsApp and by word of mouth, and by the 13th patrollers were guarding Maponya Mall, the township’s biggest retail centre. Similarly, in Katlehong on the East Rand, overnight patrols protected the only mall not yet looted in the area, using methods such as blockading key roads and slowing and redirecting traffic that older participants had learnt during the township wars of the 1990s.

As 13 July progressed, social media pages filled with SOS messages offering variations on the theme: ‘No SANDF or SAPS to replace the CPFs—media please help.’ This reflected the fact that government officials were attempting to claw back their authority by dismantling the civilian checkpoints. That afternoon, hundreds of men in Zwelisha informal settlement stormed the bridge connecting the area with Shastri Park in Phoenix, upon which they opened fire and launched home invasions. Following the incident, Shastri Park residents told the Citizen that the assault came shortly after barricades had been removed at the insistence of the local authorities.

By 14 July, large parts of KZN and Gauteng were being patrolled by vigilantes wielding everything from shotguns and rifles to cricket bats, frying pans and sticks. That afternoon, Katlehong People’s Taxi Association members went into action at Chris Hani Mall in Vosloorus, opening fire and killing a teenage boy.

Rebuilding efforts had begun by then in many areas, with ordinary citizens again leading the way in picking up the pieces amid the blood and ash: community members were operating tills and petrol pumps to enable facilities to function, suburban residents were bartering and sharing commodities, and online groups were mobilising volunteers to begin cleaning up shopping centres.

SANDF reinforcements also began arriving, which helped in stabilising matters. At 11 p.m. on the 14th, security force members appeared in Cato Ridge, Durban, accompanied by the provincial premier, Sihle Zikalala, ending round-the-clock ransacking of the area’s warehouses that had begun at 8 a.m. two days before and involved queues of looters that at times stretched three kilometres. The arrival of soldiers at an office complex in Camps Drift, Pietermaritzburg, meanwhile, caused looters to flee in all directions: some were killed by oncoming traffic, others when they either jumped or fell into the Msunduzi River and drowned. By 15 July, twenty-one corpses had been recovered on the road outside the complex.

Ramaphosa addressed the country the following evening. He characterised the events of the past week as an ‘insurrection’ that had ‘failed’. He was keen to proclaim the restoration of the state’s authority: at one point he departed from the text of his circulated speech to say of the instigators of the violence: ‘we know who they are’. This echoed claims that the state security minister, Ayanda Dlodlo, had made to the media earlier that week that her department had received eight alerts on 28 June about planned public violence and had informed the police accordingly. But the claims were rapidly contradicted by the ministers charged with acting on any such intelligence. The defence minister, Nosiviwe Mapisa-Nqakula, told a parliamentary committee meeting on 18 July that while people were referring to an insurrection or coup, she disagreed because such events had to ‘have a face’, and ‘none of [the facts] so far [point] to that’. She recanted on 20 July after the Presidency reasserted Ramaphosa’s initial insistence, but on the same day, police minister Bheki Cele (who had been reinstated in the February 2018 cabinet reshuffle) told fellow MPs during an outreach visit to Chatsworth that all incoming intelligence reports had to be signed off by him, and he had received no forewarning of the violence.

By then, the first preliminary estimates had been delivered of the losses inflicted by the Free Zuma riots. On 19 July, the South African Property Owners Association calculated that 161 malls, eleven warehouses and eight factories had been extensively damaged, while approximately 3,000 stores had been looted, at a cost to GDP of at least R50 billion. Most attention had focused on events in urban areas, but rural KwaZulu-Natal had also been deeply affected, with widespread livestock theft and crop burning, as well as extensive rioting and looting. On 20 July, the KwaZulu-Natal Agricultural Union stated that 64 per cent of the province’s towns were experiencing severe food shortages. On 23 July, government estimated that at least 330 people—79 in Gauteng and 251 in KwaZulu-Natal—had been killed during the disturbances.

~~~

- Thula Simpson is an associate professor at the University of Pretoria. His earlier research focused on the ANC’s liberation struggle, and his first book, Umkhonto we Sizwe: The ANC’s Armed Struggle, was published by Penguin in 2016.

Publisher information

‘Narrative history at its best. With prodigious detail and eloquent prose Simpson places Black South Africans at the centre of the country’s historical evolution and claims his place at the head table of contemporary historians. A masterpiece!’—Xolela Mangcu

South Africa was born in war, its growth has been marked by crises and ruptures, and it once again stands on a precipice.

History of South Africa explores the country’s tumultuous journey from the aftermath of the Second Anglo-Boer War to the Covid-19 pandemic. Drawing on never-before-published documentary evidence—including diaries, letters, eyewitness testimony and diplomatic reports—the book follows the South African people through the battles, elections, repression, resistance, strikes, insurrections, massacres, economic crashes and health crises that have shaped the nation’s character.

Tracking South Africa’s path from colony to Union and from apartheid to democracy, History of South Africa documents the influence of key figures including Pixley Seme, Jan Smuts, Lilian Ngoyi, HF Verwoerd, Nelson Mandela, Steve Biko, PW Botha, Thabo Mbeki, Jacob Zuma and Cyril Ramaphosa. The book gives detailed accounts of definitive events such as the 1922 Rand Revolt, the Defiance Campaign, Sharpeville, the Soweto uprising and the Marikana massacre. Looking beyond the country’s borders, it sheds light on the role of people such as Mohandas Gandhi, Winston Churchill, Fidel Castro and Margaret Thatcher, and unpacks military conflicts such as the World Wars, the armed struggle and the Border War. The book explores the transition to democracy and traces the phases of ANC rule, from the Rainbow Nation to transformation, state capture to ‘New Dawn’. It examines the divisive and unifying role of sport, the ups and downs of the economy, and the impact of pandemics from the Spanish flu to Aids and Covid-19.

With South Africa currently facing a crisis as severe as any in its history, the book shows that these challenges are neither unprecedented nor insurmountable, and that there are principles to be found in history that may lead us safely into the future.