The JRB presents an excerpt from the forthcoming publication The American Way: Stories of Invasion.

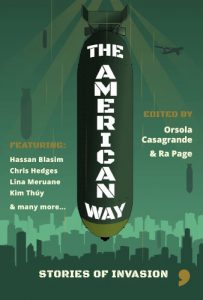

The American Way: Stories of Invasion

Edited by Ra Page and Orsola Casagrande

Comma Press, 2021

Read the excerpt:

The Lumumba Business

By Fiston Mwanza Mujila

Translated by J Bret Maney

The miners emptied out without warning like a theatrical troupe that goes offstage without a word at the end of an exhausting rehearsal. Dressed haphazardly in threadbare dungarees, sleeveless shirts, torn trousers, dented helmets, fur coats, and assorted charms to shield themselves from the cold or tropical rain, they trudged barefoot or shod in wellies, sandals, or hand-me-down shoes. Dozens, hundreds of them filed out mechanically, their bodies worn thin by fatigue and a chronic lack of sleep.

After the other miners had left, I stepped out of the boss’s sheet-metal office with a guy who went by the name of Rambo III. It was inside the office the boss liked to do his dirty work. After the recent events, he was intent on making sure the dismissals took place under what he called ‘optimal conditions’. Nicknamed ‘Patriarch’, the boss was known for his greed, his unvaryingly foul mood, and his libido. A thousand and one stories swirled around the fellow: they said he never ate breakfast and gorged himself daily on pizzas to save his pennies; they said he and his three kids squatted in a tiny apartment; they said he could stay in bed for days on end; they said he wore the same underwear from the 1st to the 30thof the month; they said he never laughed, not even with his wife—despite their being together for almost thirty years—or his children.

We walked towards my truck, which I’d parked at the entrance to the mine. Rambo III was furious. His face, usually so cheerful, was distorted by anger. Rambo III stalked ahead of me, Rambo III spat on the ground in protest, Rambo III (yep, still him) called me every name in the book, as if I was the one who had just shown him the door. I did my best to reason with him:

‘Take a deep breath, you’ll get things sorted.’

‘You traitor!’

‘Simmer down, mate.’

‘Don’t use that tone with me!’

‘C’mon, mate.’

‘I’m not your mate!’

But the guy just wouldn’t calm down. I darted around him to open the door of the truck. He gave me a withering look and climbed in.

‘Is this how you did the others?’

‘Listen, brother …’

‘You arsehole!’

‘What did you just sa–’

‘Fuck you!’

I almost hit him but stopped myself at the last second. I had chauffeured dozens of people in my beat-up truck, but I was still struggling to get used to the new role Patriarch had saddled me with: escorting home every miner the company fired. For the last few months, copper had been in free fall and the company was taking a hit. To stop the bleeding, Patriarch had begun, in his characteristically lovely way, to can the workers. Like an army general, he would stamp across the pit, stop before a miner whose appearance he didn’t like, and order him to pack up his stuff—his boots, cigarettes, hard hat—and get the hell out. All of us workers had the same meagre status as day labourers, and nobody had the gumption to stand up to Patriarch, whose arrogance was legendary. In the beginning, the company was easily getting rid of ten workers a week. When Patriarch went on his rounds, the guys didn’t even dare look at him, lest they get the dreaded order to clear out. Then, one morning in September, we were all shocked to find Ezekiel’s lifeless body in front of the company gates. The day before Patriarch had ordered him never again to set foot on the job site.

‘You, I don’t like your looks. Today’s your last day.’

‘Patriarch, you can’t just throw me out of a job like I’m some thief. I’ve always shown you respect, haven’t I?’

‘Copper’s in free fall. What do you want me to do?’

‘But Patriarch …’

‘I’m going to count to ten. When I’m done, you better be gone.’

Everybody in the company knew Ezekiel as an easy-going young man who savoured life to the fullest. He never failed to show up at work with his transistor radio. He was passionate about Zairean rumba, football and designer clothing—he could talk about it all day long even if his own wardrobe was made up of nothing but secondhand duds.

Knowing that Patriarch never changed his mind once he’d made a decision, Ezekiel picked up his radio and left. That evening, when the mine was deserted, he came back with a knife and opened his veins.

Ezekiel’s death cast a gloom over the entire company. Patriarch wasn’t seen for two days. But when he finally showed his face again, he dismissed three miners on the spot, making use of the same, feeble excuse: copper was in free fall and there was nothing he could do about it. Alas, Ezekiel’s bravura was still fresh on everyone’s mind. The fired miners returned to the mine during the night and killed themselves.

Patriarch was livid. ‘Do you think my business is a public graveyard?’ he raged. ‘Whether you like it or not, I’m going to keep kicking you to the kerb. It’s not my fault if copper prices are out of whack, and that’s all there is to it!

A week later, two more miners topped themselves. Following Ezekiel’s lead, they returned to the company gates at night and—still following Ezekiel’s lead—slit their wrists. Finding the bodies, Patriarch went ballistic:

‘What is this bullshit! You get fired, and instead of looking for another job, you come to my workplace and slash your own wrists. This behaviour is unacceptable!’

Several days later, another miner killed himself the day after he was dismissed.

Several days later, another miner killed himself the day after he was kicked to the kerb.

Several days later, another miner killed himself the day after he was dismissed.

Several days later, another miner killed himself the day after …

For a month, Patriarch didn’t fire anybody else. But if you thought that was the end of it, then you didn’t know the man. The guy knew every trick in the book and always had a plan b. He developed what he proudly termed his ‘caring companion programme’. When he fired a bloke, he would call me. ‘Driver, over here! Take him with you. Drop him off with his wife and kids and order them to keep an eye on him, because if he kills himself, it’s not my fault. He can still blast out his brains but not at my place, not in front of my business!’

I raced across town with Rambo III, flooring the truck the whole way. I wanted to be rid of my passenger, who had kept up his steady barrage of insults, as quickly as possible. To lower the tension, I turned on the radio. A Zairean musician sang acidly:

Na welaki kitoko nayo na bomengo eh

Lelo na lembi na ngai oh

Lelo na lingi, na ngai liberte

Okoki ko somba ata avion

Nako zonga te oh, nakei libela

After half an hour, we arrived in the Southern district of the city where Rambo III lived with his wife, a former history teacher redeployed as a banana seller and part-time hair stylist. As soon as she saw the company car pull up, she rushed towards us. She knew, it appeared, how Patriarch handled his dismissed workers:

‘Fired?’

‘Without the least warning!’

‘Good afternoon,’ I said, hesitantly.

Rambo III’s wife gave me a dirty look. She was probably also aware of my role in escorting home the potential suicide candidates and negotiating on Patriarch’s behalf.

‘Good day, Madam,’ I repeated.

‘What do you want from us?’

‘Patriarch gave me a message for you.’

I followed them inside. The house was stuffed with unrelated bric-a-brac: petrol cans, an automobile rim, a massive cupboard, a scuffed television set that had seen better days … On a wall gleamed a gigantic photograph of Lumumba. Rambo III’s wife motioned for me to sit down. I noticed that there were no chairs in the room.

‘Sit your ass down wherever,’ snapped Rambo III.

I lowered my backside onto a petrol can.

~~~

- Fiston Mwanza Mujila was born in Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of the Congo, in 1981, and writes poetry, prose, and theatre. Mujila lives in Graz, where he teaches African literature at Universität Graz and works with musicians in Austria on various projects. His first novel, Tram 83, won the Etisalat Prize for Literature and the Internationaler Literaturpreis from Der Haus der Kulturen der Welt. His second novel, The Villain’s Dance, was published in France in 2020 and is forthcoming in English translation from Deep Vellum.

Publisher information

Following the United States’s bungled withdrawal from Afghanistan, and the scenes of chaos at Kabul Airport, we could be forgiven for thinking we’re experiencing an ‘end of empire’ moment, that the US is entering a new, less belligerent era in its foreign policy, and that its tenure as self-appointed ‘global policeman’ is coming to an end.

Before we get our hopes up though, it’s wise to remember exactly what this policeman has done, for the world, and ask whether it’s likely to change its behaviour after any one setback. After seventy-five years of war, occupation, and political interference—installing dictators, undermining local political movements, torturing enemies, and assisting in the arrest of opposition leaders (from Öcalan to Mandela)—the US military-industrial complex doesn’t seem to know how to stop.

This anthology explores the human cost of these many interventions onto foreign soil, with stories by writers from that soil—covering everything from torture in Abu Ghraib, to coups and counterrevolutionary wars in Latin America, to all-out invasions in the Middle and Far East. Alongside testimonies from expert historians and ground-breaking journalists, these stories present a history that too many of us in the West simply pretend never happened.

Featuring: Payam Nasser • Fiston Mwanza Mujila • Ahmel Echevarría Peré • Paige Cooper • Kim Thúy • Huseyin Karabey • Lina Meruane • Gianfranco Bettin • Carol Zardetto • Jacob Ross • Gioconda Belli • Wilfredo Mármol Amaya • Gabriel Angel • Hassan Blasim • Fariba Nawa • Talal Abu Shawish • Najwa Binshatwan • Lidudumalingani Mqombothi • Murat Ozyasar • Bina Shah

About the editors

Ra Page is the CEO and co-founder of Comma Press. He has edited over twenty anthologies, most recently Resist: Stories of Uprising (2019). He is a former journalist and has also worked as a producer and director on a number of short films.

Orsola Casagrande is a journalist and filmmaker. As a journalist, she worked for twenty-five years for the Italian daily newspaper il manifesto, and is currently co-editor of the web magazine Global Rights. She has translated numerous books, as well as written her own.