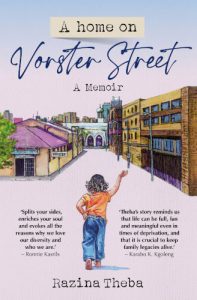

The JRB presents an excerpt from A Home on Vorster Street: A Memoir by Razina Theba.

A Home on Vorster Street: A Memoir

Razina Theba

Jonathan Ball Publishers, 2021

My maternal grandfather, Bajee, passed on when I was six but my memories of him are clear. He was a street vendor who sold brown paper shopping bags (recyclable and now fashionably artisanal) from his car which he parked in Diagonal Street in the Johannesburg CBD. For variety, he sometimes sold white Lighthouse candles. His work clothes were a three-piece suit with a pocket watch lodged in his waistcoat and a black fedora hat. His hours of trade were dictated by the setting of the sun and he never missed the Maghrib prayers at the Newtown Mosque, which was literally only a few metres away from the flat. Before the Maghrib prayer he would come home and expect his cup of chai which would have been brewing for an hour; then he would change into a simple white cotton kurta to prepare himself for the prayer. If there was time to spare, he would sit cross-legged on his single bed opposite Ma’s bed and recite the Quran.

I recall Bajee being a stern man, dignified and quiet but deeply superstitious. His superstitions had no basis in anything that could be explained. He despised whistling and was easily irritated by loud laughter, believing that we would cry soon after with an intensity proportionate to how heartily we laughed. He would eat food prepared by his daughter Khatija, who was a doctor, but not by Zubeda, who was a nurse. This had more to do with the profession than the daughter.

My cousin Tashmia and I ran past him once as he was trying to concentrate on his recitation of the Quran. He summoned us to stand at his bed and explained patiently that we were being jungli—literally, people who inhabit the Indian jungle. Popularly, the word is used to describe uncouth or unruly behaviour, but in my family it was often used to describe my curly hair which could not be tamed. One could be called jungli for banging a car door, dishing up more food than one could eat, speaking loudly: the list was endless. The word has acquired an undertone of defiance since it was imported and has now been reappropriated, and collections of cutting-edge jewellery bear the name. Bajee calmly explained that the best cure when we felt ourselves unable to contain our jungliness was to raise our index finger in line with our noses and stare at it to control ourselves. We tried.

An eight-year-old and a five-year-old, like two pressure cookers, pursing our lips together to contain ourselves. It was pointless. Our crossed eyes brought on more laughter and he simply slid his feet into his leather champals and left for the mosque. We respected Bajee enough to heed his instruction, but we did not fear him enough to force ourselves to comply.

The best way to describe the Vally family flat on Vorster Street is to picture a nine-block sudoku puzzle. The rooms in the extreme left column opened onto red stoeps, parallel to Vorster Street. From each of these rooms, one could see worshippers walking up the road, past the flat, to the Newtown Mosque. The mosque was close by, at a T-junction at the end of the road. The blocks in the middle column of the sudoku were bedrooms. The rooms in the column on the extreme right (one of which was used as a kitchen) opened into the communal space at the back for all the tenants, with outdoor bathrooms and concrete basins.

This was the Yard.

It was not unusual for tenants living on the first floor to enter the Vally family flat from Vorster Street, greet us and walk right through, exiting the kitchen door to access their flats on the first floor.

It was in this space that Bajee and Ma raised two sons and five daughters. My mother, Julie, was born to my grandparents at a time when boys were more valuable than girls. To this day, bad luck is blamed for the misaligned stars that positioned her as the fifth daughter to be born to a couple desperate for another son.

My grandparents’ eldest son, Mohammed Vally, left school at a young age to work and help Bajee support the family. Mohammed’s children, grandchildren, nieces and nephews (including me) called him Papa. An extraordinarily gifted cricketer and rugby player, as a boy he would come home with fractured bones and Ma would attend to these by setting his bones with thin planks from tomato boxes. The orthopaedic surgeon who examined the X-ray before Papa’s knee replacement surgery in his later years could not believe Ma’s handiwork. (There was less marvelling and more horror.)

Accessing decent medical care on Bajee’s income was inconceivable so Ma did her best to attend to her children’s ailments with her home remedies. Cloves were heated to release their therapeutic oils and ease my mum’s painful toothaches. Castor oil was heated and poured into her younger brother Rasid-Ahmed’s inflamed ears and countless tomato boxes were dismantled to coax Mohammed’s broken bones into setting. Ma treated chesty coughs by sewing a red flannel vest to wear against the skin to warm the chest and clear the lungs. My mum’s sister Hajira passed on at fifty, having suffered numerous untreated strep throat infections, which led to rheumatic heart disease. This condition arose from the cramped and damp conditions she lived in as a child, in Vorster Street. Ma’s salt water and turmeric concoction was no match for the bacterial infection.

These are the nuances of poverty. Every one of my mum’s siblings carried into adulthood these ailments, which would have been easily remedied by a consultation with a doctor in their childhood. My grandparents had not attended school. That they raised seven children, six of whom matriculated, with two of them becoming doctors, one a nurse and another a teacher, in the 1960s, is nothing short of remarkable. Papa left school to help his father support his siblings but his general knowledge, emotional intelligence and love of reading were unparalleled. He read every newspaper every day and one of his last phone calls to me before his cancer diagnosis was to recommend that I buy the Sunday Times newspaper just to read Ndumiso Ngcobo’s column: ‘That man has the funniest stories.’

Papa married my aunt Amina, whom my sibling and I called Gorimummy. As was customary in many Indian households, they and their children lived with Bajee and Ma. At this stage my mum’s eldest sister had married and relocated to Lichtenburg in what is now the North West Province. Her four children, my cousins, were sent to live on Vorster Street to attend high school as those in her area did not admit Indians. At its most crowded, the flat housed Bajee, Ma, Papa and Gorimummy, their children, the four remaining sisters and those four cousins.

The standard meal was kari-kitchri made from bimri rice (never basmati, which was more expensive) and flavoured sour milk without the accompanying side dishes of fried potatoes, spinach and pumpkin. Salads were prepared as a treat for special occasions. Years ago, if one wanted to indicate to a guest that she had overstayed her welcome, the host would serve kari-kitchri. It was regarded as rather a poor substitute for a meal, but with Bajee as the sole breadwinner, and before his children could contribute to the bills, this was standard fare. Strangely, the stigma attached to kari-kitchri has disappeared over time. It is now served at glamorous weddings with at least seven accompanying dishes.

- Razina Theba is an attorney and divorce mediator. Her background is primarily in law, but she has an undergraduate degree from Wits University, for which she majored in English Literature. She went on to complete an LLB degree in 2000 at Wits and practice as a labour law lecturer for a number of years. She has no formal training in creative writing. This is her first book.

~~~

Publisher information

‘This intimate personal story reminds us of humanity’s ability to continue with the business of living, that life can be full, fun and meaningful even in times of deprivation, and that it is crucial to keep family legacies alive for the next generation.’—Karabo K Kgoleng

‘Razina Theba’s A Home on Vorster Street splits your sides, enriches your soul and evokes all the reasons why we love our diversity and who we are.’—Ronnie Kasrils

As a young girl, Razina Theba makes her way every day to the tiny family flat on Vorster Street in Fordsburg. It is here, just outside of the Johannesburg city centre, where she grows up, playing in the Yard with countless cousins, learning to enjoy perfect syrupy paan and the best way to brew chai for her bajee. It is also where she observes her family’s harassment by the Security Branch, as well as her parents’ determination to make their business at the Oriental Plaza a success.

In A Home on Vorster Street, Theba witnesses the ebb and flow of a tight-knit neighbourhood trying to survive the forces of apartheid and, ultimately, where she learns of the value of family love and the enduring comfort it provides.

At times funny and charming and, at others, painful and tender, this dazzling collection of stories is a spirited exploration of a colourful Indian–Muslim family bound by loyalty to their culture, community, religion and each other.